- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The American Discovery of Europe

About this book

The American Discovery of Europe investigates the voyages of America's Native peoples to the European continent before Columbus's 1492 arrival in the "New World." The product of over twenty years of exhaustive research in libraries throughout Europe and the United States, the book paints a clear picture of the diverse and complex societies that constituted the Americas before 1492 and reveals the surprising Native American involvements in maritime trade and exploration. Starting with an encounter by Columbus himself with mysterious people who had apparently been carried across the Atlantic on favorable currents, Jack D. Forbes proceeds to explore the seagoing expertise of early Americans, theories of ancient migrations, the evidence for human origins in the Americas, and other early visitors coming from Europe to America, including the Norse. The provocative, extensively documented, and heartfelt conclusions of The American Discovery of Europe present an open challenge to received historical wisdom.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The American Discovery of Europe by Jack D. Forbes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2010Print ISBN

9780252078361, 9780252031526eBook ISBN

97802520912541.

Americans across the Atlantic:

Galway and the Certainty behind Columbus’s Voyage

Sometime during the 1470s a group of Native Americans followed the Gulf Stream from the Americas to Ireland. We don’t know if they were from the Caribbean region or from North America. We don’t know if their journey was intentional or if they were driven eastward by a storm. What we do know is that two or more Americans, at least a man and a woman, reached Galway Bay, Ireland, and were there seen by Christoforo Colomb (Columbus) long prior to his famous voyage of 1492.1

This momentous event, largely ignored by white historians, marks a beginning of the modern age, since it is precisely because of this experience that Columbus possessed the absolute certainty that he could sail westward to Cathay (Katayo or China) and India.

It is true, of course, that Columbus later learned of many arguments favoring the possibility of being able to sail directly westward from Europe to Asia. Most of these arguments were based upon logic, though, and not upon actual, concrete evidence. They were arguments derived from books that Columbus studied and annotated or from conversations and correspondence.

It is significant that all of the “hard” evidence Columbus had learned about originated with the actions of Americans or of the American environment itself. That is, the most concrete evidence that a land lay directly to the west of Europe and the offshore islands (such as the Azores) was derived from the drifting of American seacraft to the Azores, from the discovery of American bodies washed ashore, and from the arrival of carved wood and natural objects (driftwood, logs, seeds, reeds, and debris) driven by currents and winds from the west. Columbus learned of them second hand. He did not see them himself, but learned of them from other persons.

Columbus also read books, such as Historia rerum ubique gestarum of Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (Pius II), that “Indians” had been driven by storms to Europe. This was important evidence to him. He wrote in the margins of his copy of Historia rerum, opposite the reference to Indian vessels reaching Germany with people and merchandise: “Si esset maximam distanciam non potuissent venire cum fortunam sed aprobat esse prope.” Translated: “If it was an extremely great distance [between India and Germany] the vessels could not pass without ill fortune; but this proves it is near at hand.”

This remark shows that Columbus was carefully studying Aeneas’s Historia as part of his examination of the feasibility of sailing westward to Asia. It also proves that Columbus was quite interested in the evidence that Indians could sail to the coasts of Europe; but what a difference between reading of that in a book and actually seeing Indians in the flesh with one’s own eyes!

Columbus wrote also in the margins of Piccolomini’s Historia rerum the following incredibly significant comment: “Homines de catayo versus oriens venierunt. Nos vidimimus multa notabilia et specialiter in galuei ibernie virum et uxorem in duabus lignis areptis ex mirabili persona.”2 All of Columbus’s notes in Piccolomini’s Historia rerum were written in a very late Latin with terms that are not always clear, but the first part of the preceding note reads unmistakably: “People from Katayo came towards the east. We saw many notable things and specifically in Galway, Ireland, a man and wife.” The note then goes on to use late Latin terms that are presented in almost shorthand manner and that have been interpreted variously. One author translates “in duabus lignis areptis ex mirabili persona” as “deux personnes accrochíes à deux épanes, un homme et une femme, une superbe créature”; that is, “two persons hung on two wrecks, a man and a woman, a superb creature.”3

Another author translates the same phrase quite differently as “un homme et une femme de grande taille dans des barques en dérive,” or “a man and a woman of great stature [or well-built] in boats adrift.”4 Samuel Eliot Morison presents us with still a different interpretation, as “a man and a woman taken in two small boats, of wonderous aspect.”5

A fourth translator states “Hombres de Catayo vinieron al Oriente. Nosotros hemos visto muchas cosas notables y sobre todo en Galway, en Irlanda, un hombre y una mujer en unos leños arrestados por la tempestad de forma admirable.” [People from Katayo came to the east. We have seen many notable things and especially in Galway, in Ireland, a man and a woman on some wood dragged by the storm, of admirable form.]6

The problem with Columbus’s Latin is that duabus lignis means literally “with two woods” or “with two timbers or logs.” Lignis does not specifically mean either boat or wreck. The most logical conclusion is that lignis was used to refer to two dugout logs, to Native American–style piraguas or canoas as found from South America northward to Virginia and Massachusetts. Europeans would have lacked a word, other than log, to describe a solid wood boat. (Columbus later used the Arab term almadía for such craft.) Incidentally, this use of lignis confirms that the people of Katayo were indeed from America and not “flat-faced Finns or Lapps,” as Morison suggests. People from the north would not have been going in an easterly direction and they would not have had log boats. Moreover, they would not have been drifting on logs either, since the currents of that area came from America to Galway and would have carried any Sami or Finnish drifters to the far north of Norway, not to Ireland.

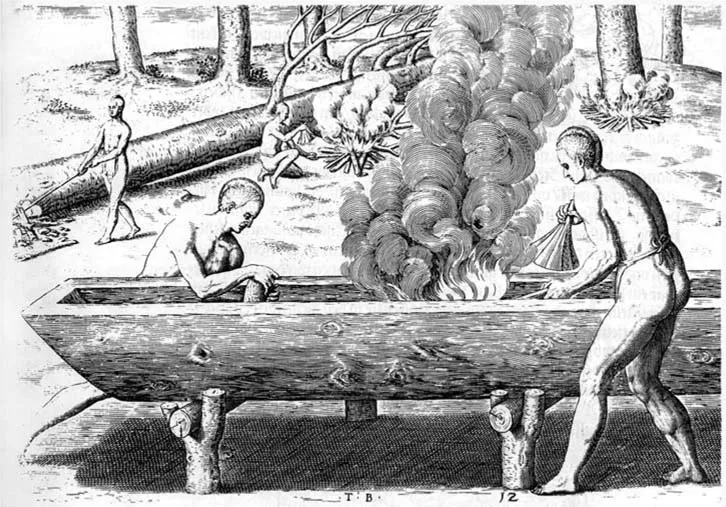

Americans in various stages of manufacturing a dugout boat. “Der Landschafft Virginia,” in Theodor De Bry, America 1590 (Munich: Verlag Konrad Kolbl, 1970), plate XI.

A complete translation has to also deal with the term areptis, which might be related to repto (to creep or crawl) or is the equivalent of Spanish arrastrar (to drag), but which more likely is related to arreptum, to get into one’s possession. Thus the complete text of Columbus should read: “People from Catayo towards the east they came. We saw many notable things and especially in Galway, Ireland, of a man and wife with two dugout logs in their possession, of marvelous form.”7

This, then, is perhaps the most exciting piece of writing ever composed by Columbus and one of the most significant paragraphs in the history of the Atlantic world. With this we have solid, indisputable evidence that Columbus and others had seen Native Americans at Galway on the west coast of Ireland and that the Americans had arrived from the west going towards the east. Columbus probably saw the Americans in 1477 and it seems very likely that this was the event that compelled him, a few years later, to begin actively preparing for a voyage to the west.

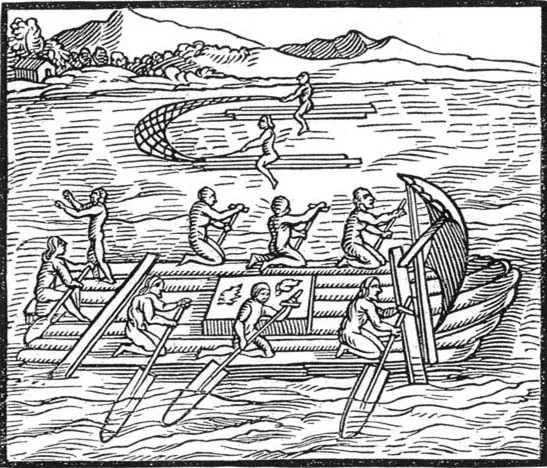

The pre-European use of rafts and sails along the Panama and South American coasts. From Girolamo Benzoni, History of the New World (London: Hakluyt, 1857), 6.

The visit, then, of the Americans to Galway in the 1470s was no mere isolated incident. It forms part of a chain of causation leading directly to the 1492 Columbus voyage and, indeed, forms one of the most important links in that chain because it was Columbus’s only firsthand experience of America prior to 1492.

But, of course, Columbus referred to the people he saw at Galway as being from Katayo (Cathay). He did not call them “Indians,” although from the location of his note in the Historia rerum it is clear that he was thinking of Indians when he wrote about people from Katayo (since he had been discussing the earlier arrival of Indians in Germany immediately before).

Let us now proceed to examine what Columbus meant by Katayo, as well as determine when he made his visit to Galway and when he wrote his comments in the margin of the Historia rerum.

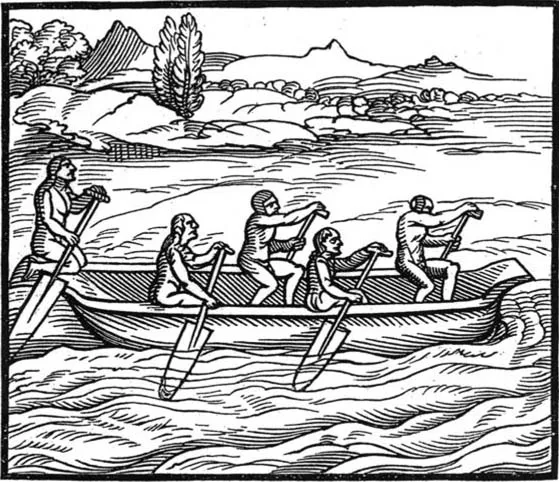

Mode of navigating in the Northern (Caribbean) Sea. From Girolamo Benzoni, History of the New World (London: Hakluyt, 1857), 6.

It has generally been supposed that Columbus visited Galway in 1477 because he himself states that he sailed northwards to the vicinity of Thule (Iceland?) in February of that year. Segundo de Ispizúa supposes that the Galway visit occurred in 1472, but this is unlikely as Colombo is witness to a will in Italy on March 20, 1472, and on August 26 he contracted with a wool merchant there. Almost a year later we again learn of him joining with his family in the sale of a horse. There are gaps from the fall of 1470 through early March 1472, but he would have been only nineteen to twenty-one years old and very possibly was learning the weaver’s trade rather than that of a sailor.8

It is much more likely that Colombo sailed to northern waters only after being shipwrecked in Portugal in the summer of 1476, since the Portuguese had a well-established trade with Galway. Moreover, the Genoese do not seem to have traded directly with Galway and their shipping was at risk due to the same kind of naval battle that had resulted in Colón’s swimming to the Portuguese coast. Morison asserts that “there is no reason to doubt that Columbus made a voyage to Galway and Iceland in the winter of 1476–1477 . . . and returned to Lisbon by spring.”9

Columbus was probably only a common seaman in early 1476 and, most likely, went to Galway and Thule in the same capacity. In 1478 he was placed in charge of a shipment of sugar to the Madeira Islands, indicating perhaps some literacy. In later years he learned to read and write in Latin and Castilian, but we can be reasonably certain that he took no written notes at Galway and that he depended upon memory for the note he made probably four years later.10

It seems likely that Colombo became interested in exploration and cosmography after his visit to Galway and Thule, and after living in the Madeira Islands and Lisbon between 1478 and the early 1480s. But it was probably after he moved to Lisbon that he began to acquire books and to make notes in their margins. According to Morison, he was ready to make his first proposals to the king of Portugal in 1484 and 1485. By 1486 he was ready to present his arguments to Spanish officialdom. Of course, he continued to do research until January 1492, when the Spanish sovereigns finally accepted his plan, as well as later.11

Our first solid evidence of Colombo’s investigations occurs in relation to his engaging in correspondence with Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, an Italian physician and cosmographer who accepted the reports of Marco Polo to the effect that Asia extended eastwards for a far greater distance than had been previously believed. Columbus was able to obtain an introduction to Toscanelli and the latter sent him a copy of his letter of 1474 to Fernâo Martins, the contents of which relate directly to Colombo’s later ideas about Katayo and Cipango (Japan). Morison states that the correspondence with Toscanelli had to have been concluded before May 1482, when the latter died.12

It is significant that Colombo’s annotations make frequent reference to the Great Khan (the ruler of the Mongol Empire that included all of China and surrounding regions) and to “Cataio.” For example, there are at least eighteen specific marginal notes on the Great Khan. Thus the reports of Marco Polo, partly as interpreted by Toscanelli, were apparently in Colombo’s mind when he made his margin notes.

The most important books written in by Colombo were Pierre d’Ailly’s Ymago Mundi and Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini’s Historia rerum ubique gestarum. Piccolomini’s work was first published in Venice in 1477, and Columbus’s copy was of that first edition. Pierre d’Ailly’s Ymago Mundi was probably first printed in 1480–83, although written in 1410–14 and available in manuscript copies at libraries before 1480. Colombo’s copy had no date of publication, but one annotation within refers to “this year of 1488,” which leads one to affirm that the copy was obtained at least by that year. Because Columbus had the reputation of being a bookseller we might assume that he obtained his Ymago Mundi as soon as it was printed, between 1480 and 1483.13

It seems quite likely that Colombo wrote most or all of his marginal notes in Piccolomini prior to about 1485, while his copy of d’Ailly was still being written in up to 1488 and even 1491 in one case. All notes in these books precede his voyage of 1492, although certain other books were being written in after his voyages to the Caribbean.

I believe that the note on Galway was written before he had an opportunity to study the Toscanelli letter of 1474 (received, presumably, by 1482). This is because it can be argued that Colombo’s thinking about “the Indies” (a term already used in 1375 on the famous Catalan map) went through two major phases: (1) a Great Khan-Katayo phase; and (2) a Great Khan-Katayo-Cipango phase.

The Catalan map of 1375 gives great prominence to “Catayo” and makes it the most important feature of east Asia. Cipango is not shown. Colombo’s notes in both Piccolomini and d’Ailly refer to the Great Khan (eighteen times in Piccolomini) to “Kataium” and “Cataio,” to Seres (a synonym for Katayo or China), to India and to India’s geographical relationship to Spain, and to other parts of Asia; but Cipango (Japan) is not a feature of any of the notes for these two books, even though d’Ailly does make a reference to the island of Cyampagu. This then constitutes Colombo’s first phase, when he was interested primarily in Katayo and India.14

It is known that Colombo was studying his copy of Piccolomini in 1481, when he wrote that year as a current date in the margin. I believe that it is at that time also that he wrote the note about Galway because presumably by 1482 he had received a copy of the Toscanelli letter to Martins. A copy of the letter in Colombo’s handwriting was found in his copy of Piccolomini’s Historia rerum and both are now located in the Biblioteca Colombina of Sevilla, as are his other books.

In the letter, Toscanelli refers to a chart that he had drawn showing Zaiton as a major port (as did the Catalan map of 1375) in the region of the Great Khan. “His seat and residence is for the most part in the province of Katay.” He goes on to state:

From the city of Lisbon westward in a straight line to the very noble city of Quinsay [Hangchow] 26 spaces are indicated on the chart. . . . This city is in the province of Mangi, evidently in the vicinity of the province of Katay, in which is the royal residence o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Americans across the Atlantic: Galway and the Certainty behind Columbus’s Voyage

- 2. The Gulf Stream and Galway: Ocean Currents and American Visitors

- 3. Seagoing Americans: Navigation in the Caribbean and Vicinity

- 4. Ancient Travelers and Migrations

- 5. From Iberia to the Baltic: Americans in Roman and Pre-Modern Europe

- 6. The Inuit Route to Europe

- 7. Native Americans Crossing the Atlantic after 1493

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index