eBook - ePub

After the Coup

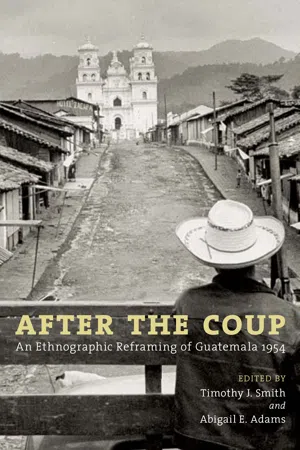

An Ethnographic Reframing of Guatemala 1954

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

After the Coup

An Ethnographic Reframing of Guatemala 1954

About this book

This exceptional collection revisits the aftermath of the 1954 coup that ousted the democratically elected Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz. Contributors frame the impact of 1954 not only in terms of the liberal reforms and coffee revolutions of the nineteenth century, but also in terms of post-1954 U.S. foreign policy and the genocide of the 1970s and 1980s. This volume is of particular interest in the current era of the United States' re-emerging foreign policy based on preemptive strikes and a presumed clash of civilizations.

Recent research and the release of newly declassified U.S. government documents underscore the importance of reading Guatemala's current history through the lens of 1954. Scholars and researchers who have worked in Guatemala from the 1940s to the present articulate how the coup fits into ethnographic representations of Guatemala. Highlighting the voices of individuals with whom they have lived and worked, the contributors also offer an unmatched understanding of how the events preceding and following the coup played out on the ground.

Contributors are Abigail E. Adams, Richard N. Adams, David Carey Jr., Christa Little-Siebold, Judith M. Maxwell, Victor D. Montejo, June C. Nash, and Timothy J. Smith.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access After the Coup by Timothy J. Smith, Abigail E Adams, Timothy J. Smith,Abigail E Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2011Print ISBN

9780252077845, 9780252035869eBook ISBN

97802520940261

Antonio Goubaud Carrera

Between the Contradictions of the Generación de 1920 and U.S. Anthropology

ABIGAIL E. ADAMS

In the spirit of this volume’s work to recontextualize the events and people from the coup, I take up the life and writings of Antonio Goubaud Carrera, first director of Guatemala’s Instituto Indigenista Nacional (IIN). Goubaud is a pivotal figure in the charged relations among Guatemalan indigenists, nationalists, and U.S. anthropologists. Goubaud was dubbed Guatemala’s “first anthropologist.” A dedicated autodidact, he also pursued formal education at Harvard and his master’s degree at the University of Chicago; he was the first professor of anthropology at Guatemala’s Universidad de San Carlos. He was also a progressive nationalist. Goubaud was a member of Guatemala’s “white” elite, of the Generación de 1920, the 1944 October Revolution, and later, Arévalo’s Guatemalan ambassador to the United States.

When the 1954 coup d’état sponsored by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) destroyed Guatemala’s new democracy, it also destroyed the IIN, the institution Goubaud had built from scratch. In the contortions of the ensuing cold war years, Goubaud’s reputation, contributions, and hopes for his nation and Maya majority were destroyed as well. The 1954 coup impoverished and flattened a rich set of intellectual and institutional relationships that were developing between the United States and Guatemala.

Recent publications reflect the damage done throughout the postcoup years. Several studies state that Goubaud and the IIN promoted cultural assimilation of Guatemala’s Maya communities. For example, one cites “an especially straightforward policy statement from a 1956 IIN document: ‘The Indian with more buying power and with national culture will be a better producer and consumer and a more active citizen. To achieve this we must adapt him scientifically through our acculturation program’” (Fischer 2001: 69–70, citing Nelson 1999: 90).

The quotation above lacks a historical treatment of the IIN document; it was published two years after the coup ended the October Revolution. The coup leaders, who were responsible for the mass murder of peasants, indigenous and nonindigenous alike, also murdered those involved with the IIN (Forster 2001; Grandin 2004; Handy 1994). They imprisoned Goubaud’s successor at the IIN, Joaquín Noval, who registered as a member of the Partido Guatemalteco de Trabajo, Guatemala’s communist party, after the coup (R. N. Adams 2000). Following the coup, any IIN influence within the state bureaucracy plummeted. By the late 1960s, the institution consisted of a few paid officials who had no working funds (Marroquin 1972). The IIN was eliminated in the mid-1980s.1

The IIN, like the seven-year-old CIA that destroyed it, was an institution that emerged to address the problems of the post–World War II era. Goubaud inaugurated the IIN during September 1945, the month that peace was established in the Pacific theater of World War II, following the atomic bombing of Japan. Goubaud explicitly placed the IIN’s inauguration in the context of postwar world events, stating: “I want to say that compared to international anarchy, Guatemala’s problem with ethnic diversity might seem small. But for us, it is our fundamental problem … among all of the ethnic groups of Guatemala’s nationality, indigenous as well as non-indigenous, there exists a marked desire for a greater mutual understanding.… We should say that this desire and our response is the mechanism by which a true nationality will be formed, one in which a large measure of understandings are common, current and shared by all of the inhabitants of the nation” (Goubaud Carrera 1964: 24).

Goubaud’s inauguration speech is the text largely cited in references to the IIN. Two lines are commonly pulled from this speech: one in which Goubaud describes indigenismo as a symptom of social discomfort, and another in which he refers to a “homogeneous nationality.”2 Some scholars have interpreted the term he used for social discomfort, “malestar social,” to imply that Goubaud considered indigenous peoples as an organic “disease” and proposed the erasure of indigenous culture.3

Another scholar combined the selected lines from the inauguration speech with Goubaud’s status as a Guatemalan elite, and with his associations with U.S. anthropologists, particularly Robert Redfield and Solomon Tax. He concluded that Goubaud imprinted Guatemalan anthropology with an “applied” focus aimed to acculturate Indians and create subjects of the state, thereby laying the institutional and ideological foundations for the counterinsurgent state’s 1980s genocide (Gonzalez Ponciano 1997).

Goubaud’s full speech, however, makes it clear that he was not proposing a eugenics solution for the “Indian problem.” Instead, Goubaud laid out a full program for the IIN. He was committed to cultural relativism and referred to Guatemala’s “two cultures,” indigenous and nonindigenous, as valid. While talking about “culturas disímiles,” he stated clearly that these were not distinct cultures, that Mayas and non-Mayas shared quite a bit with each other. One trait that members of either culture shared was a lack of national identity as Guatemalan citizens. In other words, no one was participating in a national culture. The speech is also remarkably free of romantic glorification of the Mayas, and is instead directly focused on areas of concern for all Guatemalans.

In the next four years, from 1945 through 1949, Goubaud accomplished all and more of what he set out in his inaugural speech. In this chapter, I describe his considerable achievements. I also explore the significant and heterodox intellectual currents informing Goubaud, the IIN, and the North American and Guatemalan anthropological encounter.4 Among these currents were diverse “indigenist” positions held by Guatemala’s famous Generación de 1920 and intellectual predecessors. For example, many different positions are at stake in the term that Goubaud used in his 1945 inaugural speech, “national homogeneity.” By the mid-twentieth century, other Latin American countries with indigenous majorities were promoting various forms of mestizaje in their nationalist imaginaries, but elite Guatemalans continued promoting “homogeneous nationality” to address what they saw as the “Indian problem.” The Indian problem is the thesis that indigenous peoples would hold back national development and entrance into Euro-centered modernity.

The Guatemalan elite indigenist discourses were deeply influenced, in turn, by the ethnologies already established in Guatemala by North Americans and Europeans, particularly Germans whose writings reflected an influential movement based on the emerging German notion of culture and science of ethnology. By the 1940s, Guatemala’s indigenist intellectual production became intertwined with a shift in theoretical hegemony in U.S. anthropology as well, away from the German-dominated ethnology, from historical to synchronic approaches, from spirituality, culture, and personality to social change and comparative economics.

Goubaud, who spoke and wrote unaccented English, French, and German as well as Spanish, was well-read in all these schools (Gillin 1952b: 71–73). Later he would study Mayan languages, particularly Kaqchikel. Goubaud is firmly placed among those “organic intellectuals” identified by Marta Elena Casaús Arzú, who emerged from Guatemala’s elite families and who coalesced thinking that both served and challenged elite interests.5

Goubaud’s orientation to the United States is marked throughout his biography as well and is intimately connected to his indigenist vocation. He graduated from a U.S. high school, studied a semester at Harvard, and then worked in Guatemala for U.S. expatriate Alfred Clark, of Clark Tours, through whom he met University of Chicago anthropologists Solomon Tax and Robert Redfield. Later, while studying at the University of Chicago, he met the U.S. fine arts student Frances Westbrook, who would become his wife. The couple was working in Guatemala with Tax and the Carnegie Institution when Goubaud was called to help found Guatemala’s IIN.

Goubaud left the IIN directorship in 1949 to serve as Guatemala’s ambassador to the United States at the request of President Juan José Arévalo. His appointment ended tragically March 8, 1951, when Goubaud was found dead in his room in Guatemala City after meetings with Arévalo. A few days later, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán assumed the presidency of Guatemala. The causes of Goubaud’s death remain unclear, although the event has been framed by at least two of his biographers as an assassination (Mendoza 1994: 26–36; Vela 1956).

After reviewing Goubaud’s relationships, writings, and politico-intellectual networks, I conclude that Goubaud was a complex, evolving thinker and a highly experienced fieldworker who did not promote racialist views of Maya peoples. As anthropologist Carol Smith has pointed out, Guatemala’s governors have had relatively little knowledge of life in indigenous communities (1990: 18). Goubaud was a marked exception, then, to this rule, and he diligently and publicly opposed Guatemalans searching for sweeping racialist solutions to the “Indian problem.”

Antonio Goubaud Carrera, 1902–1951

My interest in Goubaud began as a coincidence: Goubaud worked in both the isolated Oriente township of Jocotán, with Ch’orti’ Mayas, and in San Juan Chamelco, Alta Verapaz, where I worked as well. In his field notes, I found a like-minded colleague who was appalled by the poverty of Jocotán and charmed by the green beauty and seemingly progressive racial relations of the Verapaz.6 Goubaud later proved to be an invaluable resource in my research of a spirit possession cult in rural San Juan Chamelco, a cult that reemerged during Guatemala’s quincentenary year, 1992 (A. E. Adams 2009, 2001, 1999, 1996). The cult is utterly undocumented in the considerable ethnography on Q’eqchi’ Mayan speakers and the Verapaz, with one exception: Goubaud’s 1944 field notes, in which he describes cultivating a relationship with an ancestor of today’s spirit mediums (A. E. Adams 2008; see also A. E. Adams 1999).

Although I first scoured his notes for facts about my dissertation field site, and later, my new work with Maya spirit mediums, my interest in Goubaud has continued through his connections with the Generación de 1920 and Arévalo’s presidency.7 I have had the pleasure of working with Goubaud’s daughters, resulting in an exchange of materials concerning their father that has proved mutually informative.

Goubaud was born August 17, 1902, a year after David Vela, the Generación de 1920 member to whom he was closest. His birthright included membership in those elite family networks identified by Marta Elena Casaús Arzú. On two sides of his family, his paternal grandmother, Jesús Oyarzabal y Mendia, and his mother, Maria Carrera Wyld, were members of the original Basque elites of Guatemala. His paternal grandfather, Émile Goubaud, provided the connection to northern European nineteenth-century immigrants, who brought capital and connections and quickly gained placement in the Guatemalan elite’s family networks. Grand-père Émile Goubaud immigrated to Guatemala in 1853 from the French island of Ré, off the Breton coast, and represented a French publishing house. He founded the first bookstore in Central America and became one of Guatemala’s first coffee exporters. He also founded a large family with his Basque-descent bride, Jesús Oyarzabal y Mendia, with whom he had eleven children (Gillin 1952b; Vela 1956).8

One of their children, Goubaud’s father, Alberto Goubaud, was a well-to-do coffee planter and exporter. He and his wife, Maria Carrera, had four children. Alberto died suddenly during a visit in Paris when the children were quite young. Antonio’s mother became incapacitated and unable to care for her children, who were placed with relatives. Antonio was sent to the United States at the age of fifteen to continue his education, an arrangement facilitated by coffee exporter John Wright of San Francisco.9

Because of his family’s situation, the course of Goubaud’s education and upbringing differs from that of more well-known members of the Generación de 1920 cast. Unlike them, Goubaud did not attend the Instituto Nacional Central para Varones, join the Huelga de Dolores and other oppositions to Estrada Cabrera, or matriculate at the Universidad de San Carlos. He received his elementary schooling in private German academies in Guatemala, his secondary education at the Colegio Alemán of Guatemala City. In 1916, he was sent to California, where he completed high school at the Christian Brothers of La Salle’s St. Mary’s College in the Bay area.

St. Mary’s College then, as it is now, was dedicated to the liberal arts.10 The college has always matriculated Latin American students and was active in Latin American Catholic circles.11 Goubaud was enrolled in the college’s high school program from 1917 through 1921.12 He followed the standard four-year high school curriculum, with foreign language, history, vocal expression, science (chemistry, biology, physics), math, civics, music, drawing, and religion. He also appears as a featured solo or duet violinist on several special programs, such as the college graduation and awards ceremonies.13

College archives do not reveal that Goubaud belonged to any special club dedicated to indigenous issues, but John Gillin records that “[Goubaud’s] interest in Indians had been aroused while in the United States, and he set himself to reading and acquiring all the books on this subject he could obtain.” Goubaud arrived in California’s Bay area at a time of heightened interest in American Indians: that year its most famous indigenous resident, Ishi, died. Ishi, “the last wild Indian,” had been living in the University of Cal...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Reflecting upon the Historical Impact of the Coup

- 1. Antonio Goubaud Carrera: Between the Contradictions of the Generación de 1920 and U.S. Anthropology

- 2. Recovering the Truth of the 1954 Coup: Restoring Peace with Justice

- 3. A Democracy Born in Violence: Maya Perceptions of the 1944 Patzicía Massacre and the 1954 Coup

- 4. The Politics of Land, Identity, and Silencing: A Case Study from El Oriente of Guatemala, 1944–54

- 5. The Path Back to Literacy: Maya Education through War and Beyond

- 6. Democracy Delayed: The Evolution of Ethnicity in Guatemala Society, 1944–96

- Epilogue: The October Revolution and the Peace Accords

- List of Contributors

- Index