Developing Secure Attachment Through Play

Helping Vulnerable Children Build their Social and Emotional Wellbeing

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Developing Secure Attachment Through Play

Helping Vulnerable Children Build their Social and Emotional Wellbeing

About this book

Developing Secure Attachment Through Play offers a range of imaginative and engaging play-based activities, designed to help vulnerable young children forge safe attachments with their caregivers.

The book focuses on key developmental stages that may have been missed due to challenging life circumstances, such as social-emotional development, object permanence and physical and sensory development. It also considers pertinent issues including trauma, separation, loss and transition. Chapters explore each topic from a theoretical perspective, before offering case studies that illustrate the theory in practice, and a range of activities to demonstrate the effectiveness of play in developing healthy attachments.

Key features of this book include:

• 80 activities that can be carried out at home or in educational settings, designed to facilitate attachment and enhance social-emotional development;

• case vignettes exploring creative activities such as mirroring, construction play, physical play, baby doll play and messy play;

• scripts and strategies to create a safe and respectful environment for vulnerable children;

• photocopiable and downloadable resources, including early learning goals, a collection of therapeutic stories and a transition calendar

By engaging children in these activities, parents, caregivers and practitioners can help the children in their care gain a sense of belonging and develop their self-esteem. This will be a valuable resource for early years practitioners, adoptive, foster and kinship parents, and therapists and social workers supporting young children.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Social and emotional development

Introduction

Explaining attachment

Learning empathy

Key messages

- Notice patterns being repeated in the play.

- Allow the child’s expression of negative and positive emotions.

- Echoing the child’s phrases emulates the attachment dance.

Case examples

Steven, aged 3

How Steven’s foster parent helped

Carly, aged 4

How the ELP helped Carly

Activities

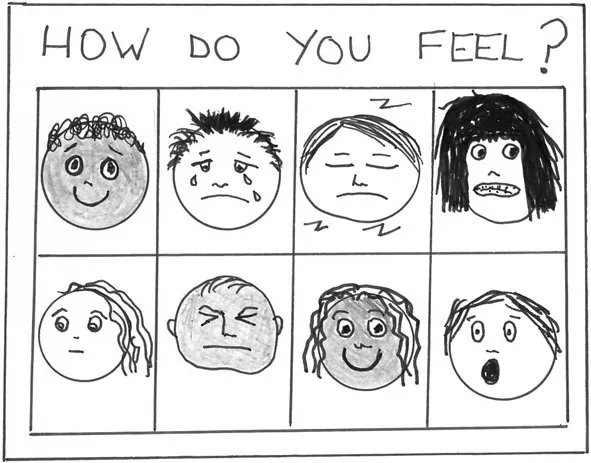

Feelings chart

Early Learning Goals

Shop play

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Social and emotional development

- 2 Trauma

- 3 Parent-child mirroring

- 4 Object permanence

- 5 Cause and effect

- 6 Physical development

- 7 Language and speech development

- 8 Separation and loss

- 9 Transition

- 10 Identity

- Appendices

- Glossary of terms

- References

- Index