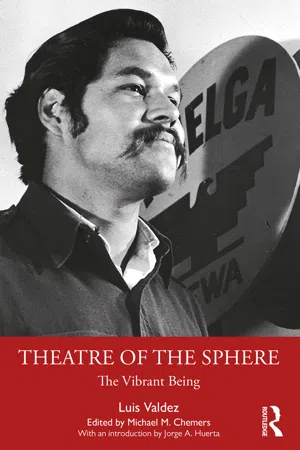

BIRTH OF A POPULAR THEATRE MOVEMENT

In a fierce spirit of self-determination, the conceptual framework and kinesthetic techniques of Theatre the Sphere, alias the Vibrant Being, evolved from the aesthetic practices of El Teatro Campesino (The Farm Workers Theatre). This means that the body, heart, mind and spirit continuum of the Vibrant Being workshop is embodied in the actos, corridos, mitos and historias of our popular theatre canon, created over 50 years of activism from the Delano Grape Strike to the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, into the twenty-first century. To better explain this, allow me to describe my personal connection to the humble roots of our coming into being.

I was born in a farm labor camp in Delano, California on June 26, 1940. As the third son of my Mexican American parents, I was on the migrant path with my farm worker family before I was old enough to walk. I worked in the fields until I was 18, when I won a scholarship to attend San Jose State University. At first, majoring in physics and mathematics, I was not preparing for a life in the theatre. Unable to resist my passions for politics and playwriting, however, I graduated with a degree in English then went to Cuba in the summer of 1964 to protest the U.S. Embargo with the Student Committee for Travel to Cuba. I met Che Guevara, played baseball with Fidel Castro, then came home in search of my own destiny. I subsequently joined the San Francisco Mime Troupe as an actor, performing in the parks and learning Commedia dell’Arte techniques. A counter-culture revolution was brewing but I felt out of place. Growing rage against racism in the Civil Rights Movement, and opposition to the Vietnam War were sparking radical notions of “guerrilla theatre” in the streets. So, in the fall of 1965 I returned to my birthplace in the central San Joaquin Valley.

It was the third week of the Delano Grape Strike, the largest farm labor dispute in the country since the Great Depression. The grapes of wrath were rotting on the vines again in John Steinbeck country. Over 30 growers had been struck in an area encompassing 1,000 square miles of vineyards. Five thousand Mexican and Filipino farm workers had left the fields. I went there hoping to talk to Cesar Chavez, the strike leader and founder of the National Farm Workers Association, about an idea for a theatre of, by, and for the striking farm workers.

It was an odd homecoming. About half of my uncles, aunts and cousins living in the Delano area were founding members of the union. The other half were scabs. I marched with the striking campesinos in the streets of Chinatown on the Westside and joined the picket lines for a few hours. But grabbing a personal moment with Cesar proved difficult… At the end of a very long day, I finally got my chance. Cesar was obviously tired, but he listened attentively, nodding gently as I pitched him my idea for a theatre of, by, and for the striking farm workers.

He seemed to like the concept from the start, but with his blunt characteristic honesty the first thing he said was: “You know, there’s no money to do theatre in Delano. Not only that, there are no actors in Delano. Not even a stage. In fact, there isn’t even any time to rehearse. All our time and effort is going into the picket lines. Do you still want to take a crack at it?” My answer was instantaneous: “Absolutely, Cesar, what an opportunity!”

True to Cesar’s word, out of necessity, El Teatro Campesino was born on the picket line without a cent. We were the Farm Workers Theater, as dirt poor as our name, but we had a life-affirming cause. The hot sun of the San Joaquin Valley witnessed our theatrical birth as spontaneous actos concocted to draw scabs out of the fields nonviolently.

As it turned out, it was a roving picket line which moved in daily car caravans across 100 square miles of struck vineyards in search of strike breakers. Given the flat open expanse of the central valley, you could say that our first actos were born in the empty space of Delano. But, in truth, Delano was not empty at all. It was full of the vibrant human spirit of La huelga. The Grape Strike was our creative matrix. In a word, our womb. It was a zero, or, as the ancient Maya put it, a full emptiness and an empty fullness.

I wrote in my initial descriptions of our work:

El Teatro Campesino exists somewhere between Brecht and Cantinflas. 1 It is a farm worker’s theater, a bi-lingual propaganda theatre, but it borrows from Mexican folk humor to such an extent that its ‘propaganda’ is salted with a wariness for human caprice. Linked by a cultural umbilical cord to the National Farm Workers Association, the Teatro lives in Delano as part of a social movement. 2

Interestingly enough, the birth metaphor was consistent from the start. So was the unmistakable implication that the Teatro’s “umbilical cord” would one day have to be severed in order for it to have a life of its own. Yet there was absolutely nothing on the horizon in the beginning to shake our dedication to La Causa.

I wrote: “Our most important aim is to reach the farm workers. All the actors are farm workers, and our single topic is the strike. We must create our own material, but this is hardly a limitation… The hardest thing at first was finding limits, some kind of dramatic form, within which to work.” 3

The fact is that in 1965 there was no blueprint for El Teatro Campesino or any kind of Chicano theatre, for that matter. We were creating something out of scratch. The Free Southern Theater, founded by Gilbert Moses and John O’Neal, had been touring the racist South for a year or so with integrated casts of black and white actors presenting “In White America” and “Waiting for Godot.” They were based in New York, but their courage inspired me. Our fledging theatre was fearlessly rooted in California’s racist equivalent of the “deep South,” the San Joaquin Valley.

The idea of a farm workers theatre almost seemed like an oxymoron—in English. We were bi- lingual because the Grape Strike had been started by heroic Filipino farmworkers, led by Larry Itliong. Half of the strikers did not even speak Spanish, including the scant Okie and Black members and student volunteers. In Spanish, El Teatro Campesino sounded as natural as the earth. The only problem was few of the campesinos had ever seen any live theatre.

As one campesino joked: oye, what’s this “triato” about? ¿Se come? (Can it be eaten?) At first the only thing they could compare us to was a circo.

So, for the sake of praise or derision, our first actors were often called payasos or clowns. That meant that, as amusing as our Teatro was, most of the strikers did not take us seriously. The few who did simply did not trust us. In Mexico, male actors were traditionally suspect. In common parlance, they were either homosexuals, womanizers or worse. In Delano, despite having the eager support of Dolores Huerta, co-founder of the union, recruiting women for the Teatro proved damn near impossible at first. Neither parents, brothers, boyfriends nor husbands were willing to allow their daughters, sisters, girlfriends or wives to act with us, though singing was allowed.

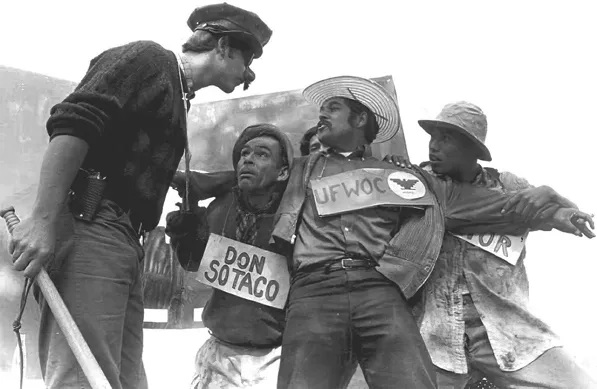

It was evident from the start that the devices of El Teatro Campesino would have to be simple, brief and direct, because they began as improvisations on the roving picket line. The seriousness of the struggle and the immense reality of the vineyards overwhelmed any temptation to do anything foolish like “acting” or clowning around. This was war. Only the most immediate use of theatre could function as a weapon.

Imagine a line of 20 cars and trucks hauling down a country road at dawn and pulling up beside a vineyard in the middle of nowhere just as the sun is breaking. After parking by the side of the road, 50 to 100 strikers emerge from their vehicles carrying picket signs, huelga flags, and bullhorns. Taking their position by the vineyard’s edge, where a crew of men, women and children is picking and packing grapes, the non-violent pickets inform the workers with calls, shouts and amplified warnings that they are breaking the strike, entreating them to leave the fields and join La Causa.

In the early weeks, this approach worked marvelously, convincing over 4,000 workers to abandon the vineyards. Hardly inclined to passively stand by while an upstart union totally talked them out of a work force, the growers induced the Kern County Sheriff’s department to follow us and aggressively, even violently, arrest the strikers. Restraining orders against the pickets were promptly issued. Then came the inevitable daily arrests, beatings and jailings. But to no avail. The strikers kept coming back. Even when provoked, we practiced nonviolence as a tactic. Thanks to Cesar’s leadership, we kept our discipline and refused to give the authorities an excuse to arrest us. In the spirit of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., we appealed to the higher consciousness of our oppressors. They arrested us anyway. With nothing but our hats for protection, huelguistas fought a daily battle of endurance.

This is where the Teatro kicked into action. We quickly found our combustive spark by lifting the spirits of the strikers while focusing the attention of strike breakers on our message. In other words, agitation and propaganda on the picket line, or unapologetically, was simply, Agit-Prop. It became a way to beat the heat and the fear. We began with a single guitar. In the face of violent threats and intimidation, we sang.

The first striker to join the Teatro was 21-year-old Agustin Lira. A song writer and guitar player, Augie had been a farm worker all his life, following the crops from Texas to California with his mother and seven brothers and sisters. We teamed up to sing songs on the picket line and at strike meetings. There were plenty of old corridos from the Mexican Revolution to choose from, but it didn’t take us long to realize that we were short of songs about our own huelga. So we translated working-class anthems from the Labor and Civil Rights movements into Spanish: “We Shall Overcome” became Nosotros venceremos, “We Shall Not Be Moved” became No nos moverán, and “Solidarity Forever” became Solidaridad pa’ siempre.

One Friday before a strike meeting, I quickly wrote some lyrics on the back of a used envelope to the tune of another Mexican corrido. That night we sang!Viva huelga en general! to the strikers for the very first time. It became our theme song. Our long days on the picket line would inevitably spawn other songs, but it took several weeks for the Teatro to begin to create theatre. The turning point came when the strikers elected me to be their next picket captain.

The union had an old green panel truck christened La Perrera or The Dogcatcher which was assigned to the picket captain. It had served as Cesar’s lead vehicle in the first days of the strike, so it had earned a certain mystique. It had a two-way radio—a powerful tool in those pre-cellular days. It also had a sturdy sun scarred roof, which could hold several strikers at once, lifting them high above the ground. This modest elevated platform on wheels became our first stage.

Practicing our own variation of Commedia dell’ Arte, we began to improvise within the framework of characters associated with the strike. Instead of Arlecchinos, Pantalones, Dottores, and Brighellas, 4 we had our Huelguistas (strikers), Patroncitos (growers), Esquiroles (scabs), and Contratistas (labor contractors). Experimenting with these four types in dozens of combinations, we defined the limits of our farm workers theatre. The biggest limitation was finding the time and place to work. Working late at night, knowing we had to be up at 4 am, a handful of volunteers would gather in the kitchen or back room of our dormitory house. Pushing back the donated army cots we slept on, we’d improvise what we called actos—10- to 15-minute pieces, with or without songs.

I insisted on calling them actos rather than skits, not only because we talked in Spanish most of the time, but because skit seemed too light a word for what we were trying to do. Classical Spanish theatre terms like cuadros, pasquines and sainetes were out of the question. On the other hand, Spanish priests had used short religious plays called autos sacramentales to convert the Indians after the conquest of Mexico. In an historically ironic reversal, I decided to call our plays actos argumentales, or simply actos, for short. In my first Teatro notebook I wrote that the argumento or dramatic action of the acto should: 1) Illuminate specific points about social problems; 2) Express what people are feeling; 3) Satirize the opposition; 4) Show or hint at a solution; and 5) Inspire the audience to social action.

Beyond that it was anybody’s ballgame. Starting from scratch with a real-life incident, character or idea, everybody in the Teatro contributed to the development of an acto. Each was intended to make a least one specific point about the strike, but improvisations during performances sharpened, altered or embellished the original concept. We used no scenery, no scripts, and no curtains. We used costumes and props only sparingly—...