eBook - ePub

American Constitutional Law

Introductory Essays and Selected Cases

Donald Grier Stephenson Jr., Alpheus Thomas Mason

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Constitutional Law

Introductory Essays and Selected Cases

Donald Grier Stephenson Jr., Alpheus Thomas Mason

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is a collection of comprehensive background essays coupled with carefully edited Supreme Court case excerpts designed to explore constitutional law and the role of the Supreme Court in its development and interpretation. Well-grounded in both theory and politics, the book endeavors to heighten students' understanding of this critical part of the American political system.

New to the 18th Edition

-

- An account of the Trump impeachments and a full discussion of the recent Supreme Court transitions including recent Supreme Court transitions including the fraught Kavanaugh hearings, the death of Ruth Bader Ginsberg, and the nomination process surrounding Amy Coney Barrett.

-

- Fourteen new cases carefully edited and excerpted, including Chifalo v. Washington (2020) on the Electoral College, Masterpiece Cakeshop (2018) on gay rights, and three Trump cases as well.

-

- Thirty-one new cases discussed in chapter essays in addition.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is American Constitutional Law an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access American Constitutional Law by Donald Grier Stephenson Jr., Alpheus Thomas Mason in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Jurisdiction and Organization of the Federal Courts

DOI: 10.4324/9781003164340-2

[R]eversal by a higher court is not proof that justice is thereby better done. There is no doubt that if there were a super-Supreme Court, a substantial proportion of our reversals of state courts would also be reversed. We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final.

—Justice Robert H. Jackson (1953)

American constitutional law represents only a tiny fraction of the entire corpus of the law. Routine litigation between private parties seldom falls into the category of “cases” to which the judicial power of the Supreme Court extends. Even cases involving constitutional questions may be sidestepped. The Supreme Court of the United States is not “a super legal aid bureau.”

This chapter presents certain rules and procedures guiding the justices in choosing the cases they will decide and sketches the major steps leading to a decision. The rules governing jurisdiction and standing to sue vest in the justices’ considerable discretionary power as to when they will act or refuse to act. The justices control their workload by selecting the cases that demand attention at the highest level. In the governing process, the Supreme Court has an important, if circumscribed, role to play.

The Judicial Power

The Constitution in Article III makes possible the resolution of certain legal disputes in national, as opposed to state, courts. One significant difference between American government under the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution was the provision in the latter for a system of national courts. Under the Articles, there was not even a Supreme Court.

Fifty-Two Judicial Systems. Civilian courts in the United States are spread across 52 separate judicial systems: the court systems of the 50 states plus the District of Columbia, and the court system of the national government. The latter are commonly referred to, somewhat misleadingly, as federal courts and exist because of acts of Congress. By contrast, state courts derive their existence from the constitutions and statutes of their respective states. This dual system of federal and state courts means that almost everyone in any of the 50 states is simultaneously within the jurisdiction, or reach, of two judicial systems, one state and the other federal. Jurisdiction refers to the authority a court has to decide a case. The term has two basic dimensions: who and what. The first identifies the parties who may take a case into a particular court, or who may be brought before a court. The second, the “what,” refers to the subject matter the parties may raise in their case.

According to Article III, federal judicial power extends to (1) cases arising under the Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made under the authority of the United States; (2) admiralty and maritime cases; (3) controversies between two or more states; (4) controversies to which the United States is a party, even where the other party is a state; (5) suits between citizens of different states; and (6) cases begun by a state against a citizen of another state or against another country. (As explained in Chapter Four, the Eleventh Amendment modified Article III to bar suits brought against a state by a citizen of another state or country.) The Constitution vests this judicial power of the United States in “one Supreme Court and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” This provision is not self-executing, and Congress at the outset of the government in 1789 created a system of lower federal courts in addition to the Supreme Court.

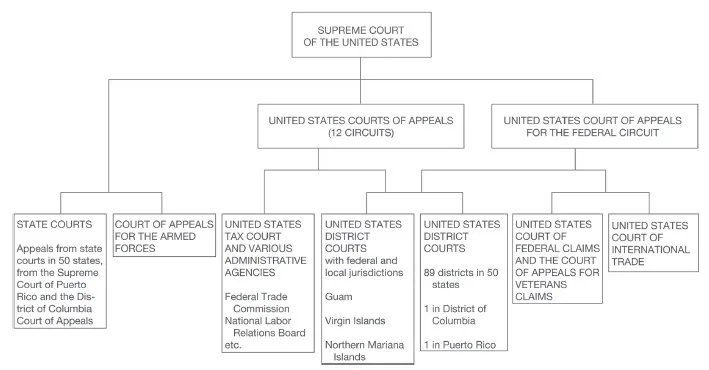

As currently organized, this system consists of (1) a court of appeals for each of the 11 judicial circuits, plus one for the District of Columbia; (2) district courts, of which there are now 94 (89 in the 50 states, plus one in the District of Columbia and one in Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam); and (3) other courts, such as the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. (See Figure 1.1.) Moreover, each district includes a bankruptcy court as a unit of the district court. Bankruptcy judges are appointed for renewable 14-year terms by the U.S. court of appeals for each circuit.

FIGURE 1.1 The National Court System

Cases in the federal courts usually originate in the district courts. Cases in state courts may qualify for review by the U.S. Supreme Court if they raise a federal question.

Source: Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

The Supreme Court, courts of appeals, and the district courts within the 50 states, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico are known as constitutional courts, or Article III courts. Their judges are appointed by the president, confirmed by the Senate, and enjoy the constitutional assurances of tenure “during good behavior” (effectively lifetime appointment) and no reduction in salary. Specialized courts such as the Court of Federal Claims or the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces are legislative courts, or Article I courts, meaning that they were created by Congress in furtherance of a power granted by Article I. In contrast to Article III courts, Congress has full power over the salaries and tenure of judges of these Article I courts and may assign administrative or legislative duties to them. The district courts in the territories of Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands are also Article I courts. The distinction between Article III and Article I judges has real operational significance. In Nguyen v. United States (2003), the Supreme Court vacated two judgments of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals because the panel of three judges included the chief judge of the District Court of the Northern Mariana Islands (an Article I judge), who was sitting by designation with the Article III appeals court judges.

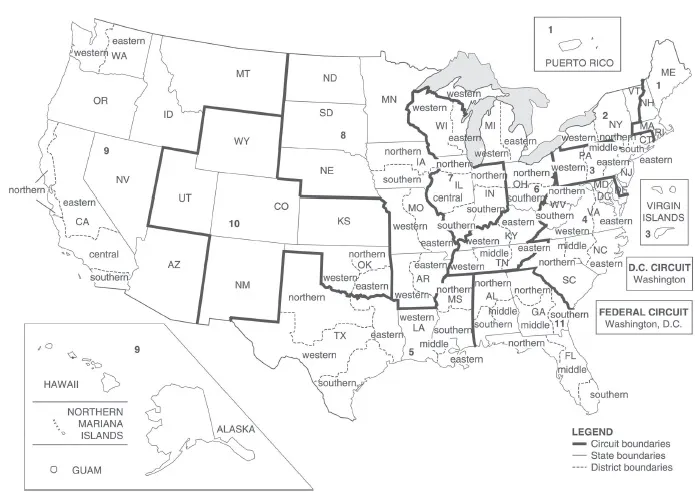

Jurisdiction of the District Courts. The district courts are the trial courts and workhorses of the federal judicial system. (See Figure 1.2.) Their original jurisdiction includes cases that raise a federal question and cases that involve more than $75,000 where the parties are citizens of different states. (A court has original jurisdiction when a case begins or originates there, and appellate jurisdiction when a case involves review of the decision of a lower court. A federal question is one that involves the meaning and/or application of the Constitution, a statute, or a treaty of the United States.) Two wholly independent bases of jurisdiction are thus provided: The first is defined by the nature of the question, and the second (diversity jurisdiction) by the citizenship of the parties and the amount at stake. Diversity jurisdiction allows cases presenting issues normally heard in state court to be tried in federal court. District courts also have supervisory powers over bankruptcy courts within each district and appellate jurisdiction with respect to a few classes of cases tried before U.S. magistrate judges. These judicial officers are appointed by majority vote of the active district judges of the court, with those in full-time positions serving eight-year terms. Magistrate judges issue search warrants, conduct arraignments of persons charged with federal crimes, and perform other duties assigned by their district court.

FIGURE 1.2 Geographic Boundaries of the U.S. Courts of Appeals and U.S. District Courts

This map shows how the 94 U.S. District Courts and the 13 U.S. Courts of Appeals exist with the court systems of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The District Courts include 89 divided among the 50 states, plus one each for the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands.

Source: Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Jurisdiction of the Courts of Appeals. Congress has given the courts of appeals jurisdiction in appeals taken from the district courts within their respective circuits, from judgments of the Tax Court, and from the rulings of particular administrative and regulatory agencies such as the National Labor Relations Board and the Securities and Exchange Commission. In addition, courts of appeals may review cases from the district courts in the territories. (For example, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands are part of the Ninth Circuit.) The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has a more specialized jurisdiction. Unlike the other 12, it hears appeals in patent, trademark, and copyright cases and in certain administrative law matters from district courts in all circuits as well as from the Court of Federal Claims, Court of International Trade, Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, and specified administrative bodies.

Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court’s jurisdiction is in two parts: original and appellate. The Court’s original jurisdiction is specified in Article III and can be neither diminished nor enlarged by Congress. It includes four kinds of disputes: (1) cases between one of the states and the national government; (2) cases between two or more states; (3) cases involving foreign ambassadors, ministers, or consuls; and (4) cases begun by a state against a citizen of another state or against another country. Only controversies between states qualify today exclusively as original cases in the Supreme Court. For the others, Congress has given concurrent jurisdiction to the lower federal courts. As a result, almost all of the Court’s cases come from its appellate jurisdiction.

According to Article III, the Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction “in all other cases both … as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.” Congress, in other words, decides which categories of cases in the lower courts qualify for review by the Supreme Court. Not until 1889, for example, was there a right of appeal to the Supreme Court in some federal criminal cases. Perhaps Congress could even deprive the Court of all appellate review and make final the decisions of l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Brief Contents

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- The Constitution of the United States of America

- Introduction A Political Supreme Court

- Chapter One Jurisdiction and Organization of the Federal Courts

- Chapter Two The Constitution, the Supreme Court, and Judicial Review

- Chapter Three Congress and the President

- Chapter Four Federalism

- Chapter Five The Electoral Process

- Chapter Six The Commerce Clause

- Chapter Seven National Taxing and Spending Power

- Chapter Eight Property Rights and the Development of Due Process

- Chapter Nine The Bill of Rights and the Second Amendment

- Chapter Ten Criminal Justice

- Chapter Eleven Freedom of Expression

- Chapter Twelve Religious Liberty

- Chapter Thirteen Privacy

- Chapter Fourteen Equal Protection of the Laws

- Chapter Fifteen Security and Freedom in Wartime and Pandemic

- Appendix A Justices of the Supreme Court

- Appendix B Presidents and Justices

- Appendix C American Constitutional Development as Reflected in a Chronology of Cases Reprinted in This Book

- Glossary

- Index of Cases

- Index of Subjects and Names