The Restorative Prison

Essays on Inmate Peer Ministry and Prosocial Corrections

- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Restorative Prison

Essays on Inmate Peer Ministry and Prosocial Corrections

About this book

Drawing on work from inside some of America's largest and toughest prisons, this book documents an alternative model of "restorative corrections" utilizing the lived experience of successful inmates, fast disrupting traditional models of correctional programming. While research documents a strong desire among those serving time in prison to redeem themselves, inmates often confront a profound lack of opportunity for achieving redemption. In a system that has become obsessively and dysfunctionally punitive, often fewer than 10% of prisoners receive any programming. Incarcerated citizens emerge from prisons in the United States to reoffend at profoundly high rates, with the majority of released prisoners ending up back in prison within five years. In this book, the authors describe a transformative agenda for incentivizing and rewarding good behavior inside prisons, rapidly proving to be a disruptive alternative to mainstream corrections and offering hope for a positive future.

The authors' expertise on the impact of faith-based programs on recidivism reduction and prisoner reentry allows them to delve into the principles behind inmate-led religious services and other prosocial programs—to show how those incarcerated may come to consider their existence as meaningful despite their criminal past and current incarceration. Religious practice is shown to facilitate the kind of transformational "identity work" that leads to desistance that involves a change in worldview and self-concept, and which may lead a prisoner to see and interpret reality in a fundamentally different way. With participation in religion protected by the U.S. Constitution, these model programs are helping prison administrators weather financial challenges while also helping make prisons less punitive, more transparent, and emotionally restorative.

This book is essential reading for scholars of corrections, offender reentry, community corrections, and religion and crime, as well as professionals and volunteers involved in correctional counseling and prison ministry.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

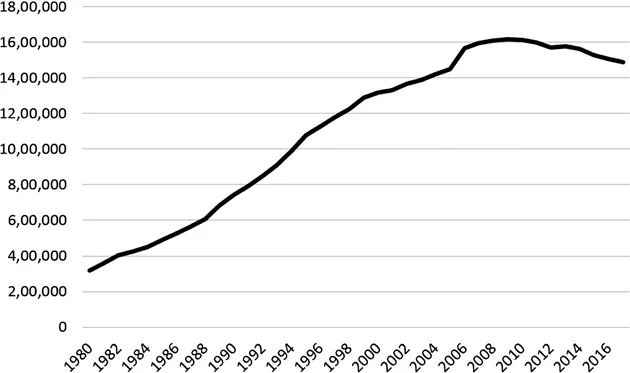

The Consequences of Failing Prisons

The Human Drain: How Incarceration Affects Families

The Financial Drain: The Economic Impact of Overreliance on Incarceration

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- 1 The Consequences of Failing Prisons

- 2 Can Prisons Model Virtuous Behavior?

- 3 How Religion Contributes to Volunteerism, Prosocial Behavior, and Positive Criminology

- 4 The Disruptive Potential of Offender-led Programs: “Lived Experience” and Inmate Ministry

- 5 Offender-Led Religious Movements and Rethinking Incarceration

- 6 Wounded Healers in “Failed State” Prisons: A Case Study of Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman

- 7 Lessons We Can Learn from Prisoners

- 8 Toward Restorative Corrections: A Movement Well Underway

- 9 Epilogue

- Index