Introduction

Over the decades, artists have creatively probed the many (mis)identifications, pleasures and objectifications of stereotyped femininity. As the 1984 Australian feminist pub-rock classic told it, ‘the girl in the mirror ain’t the same as the girl on the wall’.1 And who was that ‘man in the head’ who made that girl so self-conscious, prompting her to constantly watch herself being watched?2 Why do women internalise objectifying gender representations? From the later 1960s, these questions were asked across a broad spectrum of feminist consciousness-raising scenarios. The more important question then became: once feminists stood behind the camera, what alternative images of femininity, including female beauty, could we create? This chapter investigates these speculations on the contradictory pleasures of feminine display and female spectatorship.

We argue that feminism re-routed Marxist theories of ideological interpellation through creative analyses of mass media and high art representational systems, helping to drive the politicisation of culture as a relatively autonomous sphere of New Left political action. We use the term ‘New Left’ to designate broad, post-war shifts within Marxist theory and practice from an orthodox framework of economic base and superstructure, which had held the sphere of economic production as determinant (at its simplest, the idea that consciousness was determined by one’s relation to the means of production).3 Yet what if one’s consciousness is contoured through capitalism’s reproductive relations, as is the case for half the world’s population, i.e. women? Moreover, orthodox Marxism could not adequately account for the non-repressive yet compelling ideological workings of the capitalist state. Traditional reflection theory was too mechanistic to be useful when analysing our increasingly mediatised and information-based post-war world economies. The rise of post-war social movements such as civil rights, anti-colonial and anti-nuclear movements, along with battles over the environment and women’s and gay liberation, forced a radical re-thinking of the primacy of class and the privileging of the proletariat as driver of historical progress. This dynamic field, then designated as the New Left, held great potential for coalitional action that is only now being realised in today’s mass social movements.

Work on the politics of representation arose through feminist attempts to understand women’s inculcation of oppressive feminine images and roles: stereotypes that proved resistant to the simple call-out of false consciousness. Why did we hold beliefs and self-perceptions that were clearly not in our interests, including repressive ideas of white, straight and bourgeois femininity? From the 1970s, feminism addressed the complex ideological workings of representational systems, including those of the mass media and high art. This chapter sketches a non-linear herstory of this creative praxis, from the early call-out of sexist imagery and promotion of positive images, to structurally focussed, deconstructivist analyses of representational systems and new materialist emphasis on the dispersal of identity.

We start with the observation that many activists in Women’s Liberation in the 1970s logged mass media agents of feminine socialisation and presumed an equally clear alternative: to re-educate women by documenting real women going about their daily lives.4 This creative call drew initial inspiration from the imagery of the African American civil rights movement. The feminist debt to Black Pride linked to broader connections with realist traditions in Europe and the Americas that endowed the imagery of the oppressed with progressive political and moral value. Could we similarly calibrate feminist identity along a spectrum of exploitation and struggle? However, the bourgeois moral codes of social realism (best expressed in nineteenth-century realist literature, painting and later photo-documentary) had studiously avoided images of the unworthy poor (no drinkers, no wasters, no wanton women, no bad mothers). For instance, first wave feminist struggles for (white) women’s suffrage had been framed by images of deserving citizenry, social purity and maternal responsibility. Interwar photo-documentary promoted the stoic, maternal body (Dorothea Lange) and the dignity of women’s labour (Marion Post Wolcott) to command respect, compassion and support within an American New Deal politics. Was that what we wanted: a social realist antidote to Media She?5 However the low-key, photo-documentary imagery of feminist magazines in this period often lacked the visual grab of televisual glamour, and the reflection theories that underpinned the positive imagery project could not penetrate the psychologically compelling visual dynamics of sophisticated media technologies, beyond the call to Simply Say No to gender stereotyping.6

This chapter argues that things were a little different in the artist’s studio, however. Many second wave feminists turned the tables on the historical power relations between photographer and subject when creating photo-documentary images of women on the factory floor, typing pool and child care centre in feminist magazines, industrial photography and in later Art and Working Life trade union projects.7 They sought to avoid the photogenic objectifications of traditional photo-documentary as undermining feminism’s aim to promote inclusive and self-generated subjectivities. Most artists realised that the documentary excess through which we could create ‘women’s essence’ was inherently connected with the dynamics of image making. Contrary to accepted herstories, very few visual artists in the 1970s wholeheartedly relied on simple realist aesthetic strategies—even those early attempts to create positive images of non-traditional womanhood. One problem they faced was how to refute the mass media objectification of women’s bodies and the commodification of female sexuality, and to still remain pro-sex. Some artists tried to turn the pornographic tables through central core imagery, which sexualised the female body through exaggerated proximity and a disconcerting literalism so as to resist the closures of objectified representation. We will discuss this dishevelling imagery later in the chapter. Other artists were more ambivalent about using women’s bodies in artwork at all, especially naked bodies, as they could be so easily co-opted. Yet we did not want to simply reprise the social purity tenets of first wave feminism, as was discussed through the so-called ‘pornography debates’ from the later 1970s.8 Widespread disquiet with the politics of representation—particularly the depiction, signification and agency of bodies—soon broadened into largely fruitful and often heated discussions around essentialism. To avoid the dubious anti-sex morality of social purity feminism, which too-easily dovetailed with the resurgent Christian Right, many artists developed a highly sophisticated studio critique by reaching into the theoretical toolbox9 of psychoanalysis and post-structuralist semiotics to explore the psycho-social, ideological operations of visual signification. A dynamic and relational approach to power, visual pleasure and the creation of meaning enabled artists to work within and against the racialised, gender and sexual inscriptions of mass media and canonical art imagery. Here we encountered another challenge: that of avoiding the docility of misrecognised feminine subjectivity ‘called into being’ through the psycho-social structures of capitalism’s ‘ideological state apparatuses’.10 Seeking a more active and embodied agency for women, feminist artists moved away from the analysis of gender representation within fixed and generalisable ideological systems. For one thing, First Nations and Women of Colour contested the ahistorical and Eurocentric terminology of the politics of representation, specifically any broad claims made for the applicability of semiotic and psychoanalytic frameworks. Their art projects looked elsewhere to indicate the dynamics of subaltern women’s subjectification as embodied, situated and resisted. These projects resonated, for feminist studio research has always revealed the dynamics of subjectivity to be actively embodied and relational in ways that could not be easily reduced to a priori ideological or linguistic frameworks.

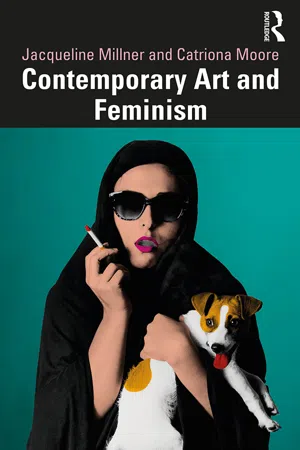

This realisation has prompted a broad shift away from the ‘politics of representation’ to embrace a ‘politics of acts’ that could enable interventions in the cultural sphere to coalesce with activism across other social and political spaces, as in the Occupy movements, campaigns for climate justice, First Nations’ sovereignty, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. This chapter gives weight to these latter strategies of corporeal feminism, given they dominated feminist studio research since the 1970s and continue to inform a diversity of current practices. We observe these subtle shifts in focus and a broadening, feminist visual lexicon. Whilst feminist aesthetics has no singular historical arc or trajectory, we note that strategies of Lettrist-styled détournement or re-routing of existing sexist and racist imagery have increasingly relayed and mutated across diverse regions and over time. We also mark how the use of psychoanalytic and semiotic frameworks to destabilise the psycho-social dynamics of the Western art canon, advertising and Hollywood cinema that were prevalent in the West from the 1970s have been overtaken by more assertive affirmations. Much recent work simply abandons Western feminine tropes of whiteness, thinness, wealth or bourgeois decorum in embodied resistances and acts of sovereignty which lay claim to female beauty, yet do not reprise the recuperative identity politics of Coming Out or ‘I Am Woman’. In a moment when the visual rhetoric of identity politics has become a divisive and politically toxic weapon of right wing politics, feminists continue to inform and manifest, in very novel ways, a fluid, connective identitarian field (‘We are George Floyd/David Dungay’/‘I can’t breathe’/‘#MeToo’). Indeed, we would question whether the term identity politics remains a relevant moniker fo...