eBook - ePub

The History of Educational Measurement

Key Advancements in Theory, Policy, and Practice

Brian E. Clauser, Michael B. Bunch, Brian E. Clauser, Michael B. Bunch

This is a test

Share book

- 366 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The History of Educational Measurement

Key Advancements in Theory, Policy, and Practice

Brian E. Clauser, Michael B. Bunch, Brian E. Clauser, Michael B. Bunch

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The History of Educational Measurement collects essays on the most important topics in educational testing, measurement, and psychometrics. Authored by the field's top scholars, this book offers unique historical viewpoints, from origins to modern applications, of formal testing programs and mental measurement theories. Topics as varied as large-scale testing, validity, item-response theory, federal involvement, and notable assessment controversies complete a survey of the field's greatest challenges and most important achievements. Graduate students, researchers, industry professionals, and other stakeholders will find this volume relevant for years to come.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The History of Educational Measurement an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The History of Educational Measurement by Brian E. Clauser, Michael B. Bunch, Brian E. Clauser, Michael B. Bunch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Testing Movements

1

Early Efforts

The rise of educational assessment in the United States is closely tied to attempts to create a formal educational system. In the 1600s peoples from Europe, including Puritans, Huguenots, Anabaptists, and Quakers, came to North America to escape religious persecution. Once they arrived, daily life was mostly a matter of survival. When education occurred, it was primarily at home. The largest influence on education in the American colonies was religion. This chapter describes the roots of the US educational system and the beginnings of student assessment. In the early 1600s all religious leaders regarded education of their young people as essential to ensuring that youth could read the Bible.

Chronological Perspective

To foster a better understanding of education and how primitive classrooms and schools in the early 17th century functioned, we offer the following chronology of technological developments:

| 1809: | first chalkboard in a classroom |

| 1865: | quality pencils mass-produced |

| 1870: | inexpensive paper mass-produced for students to use in the classroom |

| 1870: | steel pens mass-produced, replacing inefficient quill pens |

| 1870: | “magic lanterns” used in schools to project images from glass plates |

| 1936: | first electronic computer |

| 1960: | first “modern” overhead projectors in classrooms |

| 1967: | first hand-held calculator prototype “Cal Tech” (created by Texas Instruments) |

| 1969: | first form of the internet, ARPANET |

Historical Perspective of Education in the American Colonies

The first attempt to establish a school in the colonies was in 1619–20 by the London Company, with the goal of educating Powhatan Indian children in Christianity. This attempt was followed by the establishment of the East India School, which focused on educating white children only. In1634, the Syms-Eaton Academy (aka Syms-Eaton Free School), America’s first free public school, was created in Hampton, Virginia by Benjamin Syms. The mission of the school was to teach white children from adjoining parishes along the Poquoson River. (Heatwole, 1916; Armstrong, 1950).

A year later, the Latin Grammar School was founded in Boston (Jeynes, 2007). The school followed the Latin school tradition that began in Europe in the 14th century. Instruction was focused on Latin, religion, and classical literature. Graduates were to become leaders in the church, local government, or the judicial system. Most graduates of Boston Latin School initially did not go on to college, since business and professions did not typically require college training. The Latin School admitted only male students and hired only male teachers until well into the 1800s (Cohen, 1974). The first Girls’ Latin School was founded in 1877. The Boston Latin School is still flourishing today.

The first private institution of higher education, Harvard, was established in Newtown (now Cambridge), Massachusetts in 1636. When it first opened, it served nine students. In 1640, a Puritan minister, Henry Dunster, became the first president of Harvard and modeled the pedagogical format on that of Cambridge. In his first several years he taught all courses himself. Harvard graduated its first class in 1642 (Morison, 1930).

The Massachusetts Bay colony continued to open schools in every town. One by one, villages founded schools, supporting them with a building, land, and on occasion public funding. In 1647, the colony began to require by law secondary schools in the larger cities, as part of an effort to ensure the basic literacy and religious inculcation of all citizens. The importance of religious and moral training was even more apparent in legislation passed that year that was referred to as the “Old Deluder Satan Act.” The legislation affirmed that Satan intended for people to be ignorant, especially when it came to knowledge of the Bible. The law mandated that each community ensure that their youth were educated and able to read the Bible. It required that each community of 50 or more householders assign at least one person to teach all children in that community (Fraser, 2019). This teacher was expected to teach the children to read and write, and he would receive pay from the townspeople.

It should be noted that women teachers did not begin to appear until the Revolutionary War, and then only because of the shortage of males due to the war and labor demands. The contents of the legislation further instructed towns of 100 or more households to establish grammar schools. These schools were designed to prepare children so that they would one day be capable to study at a university (Fraser, 2019).

These laws were not focused so much on compulsory education as on learning. They reasserted the Puritan belief that the primary responsibility for educating children belonged to the parents. Puritans believed that even if the schools failed to perform their function, it was ultimately the responsibility of the parents to ensure that their children were properly educated (Cubberley, 1920). Current research still indicates that there is a strong connection between educational success and parental involvement (Kelly, 2020).

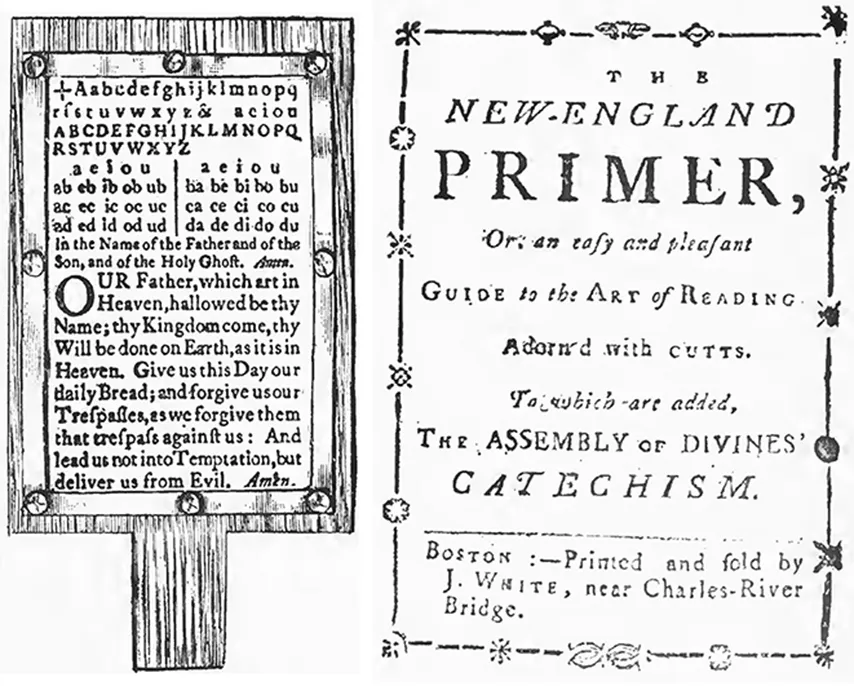

Formal education in colonial America included reading, writing, simple mathematics, poetry, and prayers. Paper and textbooks were almost nonexistent, so the assessment of students primarily entailed recitation and subsequent memorization of their lessons. The three most-used formats of instruction were the Bible, a hornbook, and a primer. The hornbook was a carry-over from mid-fifteenth century England. Early settlers brought them to America. It consisted of a sheet of paper that was nailed to a board and covered with transparent horn (or shellacked) to help preserve the writing on the paper (Figure 1.1). The board had a handle that a student could hold while reading. The handle was often perforated so it could attach to a student’s belt. Typically, hornbooks included the alphabet in capital and small letters, followed by combinations of vowels with consonants to form syllables, the Lord’s Prayer, and Roman numerals (Plimpton, 1916, Meriwether, 1907).

Figure 1.1 An example of a typical hornbook (left) and a version of the New England Primer (right)

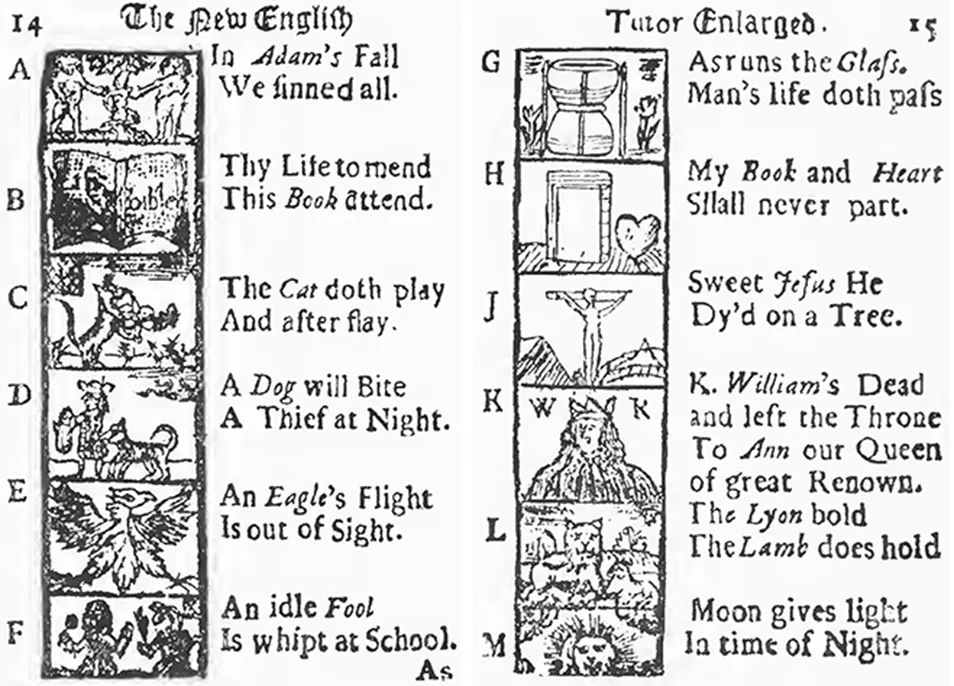

The New England Primer was the first actual “book” published for use in grammar schools in the late 1680s by Benjamin Harris, an English bookseller and writer who claimed to be one of the first journalists in the colonies. The selections in The New England Primer varied somewhat over time, although there was standard content designed for beginning readers. Typical content included the alphabet, vowels, consonants, double letters, and syllabaries of two to six letters. The original Primer was a 90-page work and contained religious maxims, woodcuts, alphabetical rhymes, acronyms, and a catechism, including moral lessons. Examples of the woodcuts and rhymes to help students learn the alphabet are shown in Figure 1.2. Printing presses did not exist outside of Massachusetts until they appeared in St. Mary’s City (MD) and Philadelphia, in 1685 (Jeynes, 2007).

Figure 1.2 An example of woodcut figures that accompanied rhymed phrases designed to help children learn the alphabet

Until the mid-nineteenth century, most teachers in America were young white men. There were, of course, some female teachers (e.g., women in cities who taught children the alphabet, or farm girls who taught groups of young children during a community’s short summer session). But when districts recruited schoolmasters to take charge of their winter session scholars—boys and girls of all ages—they commonly hired men because men were considered more qualified to teach and discipline, an essential ingredient to an efficient school. It was not very common for schoolmasters to teach beyond their late 20s, usually abandoning their teaching career by age 25. The defection rate was extremely high—over 95% within five years of starting. Usually men taught while training for other careers like law or ministry. The wages were low, the work was seasonal, and there were often many better paying opportunities than teaching.

Overwhelmingly, teachers felt that absolute adherence to fundamental teachings was the best way to pass on values held in common. If children were disobedient in any way, the teacher could yank them from their benches for the liberal application of the master’s whip to drive the devil from the child’s body. If children did something particularly egregious that interfered with their redemption, or if the schoolmaster was unusually strict, they could be required to sit for a time in yokes similar to those worn by oxen, while they reflected on their transgressions.

Tutoring was also a common form of education in the colonial period. Philosophers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and William Penn all strongly suggested that public schools were unhealthy and immoral. Penn suggested that it was better to have an “igneous” tutor in his house versus exposing his children to the vile impressions of other children in a school setting. (Gathier, 2008). Many ministers also became tutors. Tutors or governesses had more authority over their students than teachers do today. They could spank or whip the students or sit them in the corner if they misbehaved. When a student talked too much, the tutor placed a whispering stick in the talkative student’s mouth. This stick, held in place by a strip of cloth, eliminated talking. Tutors also used dunce caps and nose pinchers to keep students in line.

Another interesting mode of education was sending children to live with another family to receive lodging and instruction. In many cases parents sought to send their children to live with the more affluent so they could acquire not only an education but manners and habits such families could provide. It was also thought that parents could not discipline their children as well as a foster family could. It has been argued that this process was also for economic reasons as the student was also put to work for the acquiring family. Sometimes, to clarify the arrangement, formal agreements were written up. The greater the potential to learn more skills, the more parents would have to pay. That is, an education would be exchanged for child labor.

By the early 1700s most children carried a book-sized writing slate with a wooden border. The slate was used to practice writing and penmanship. Typically, a student would scratch the slate with a slate “pencil” or cylinder of rock. Eventually, the slate pencil was replaced by soft chalk. Students were not able to retain any of their work to review or study later. The main pedagogical tool was memorization, and the main form of assessment was through recitation led by the teacher.

Upon the formation of the United States Government, education was taken up by the individual states – the civic purpose superseded the older religious aim. District schools and academies at first were dominant. Gradually graded town schools ...