- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

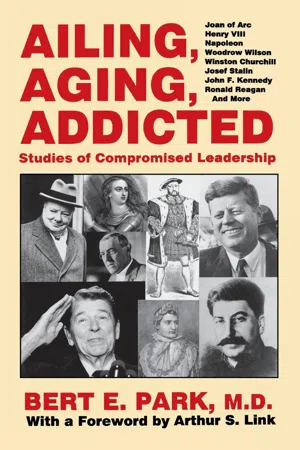

Yes, you can access Ailing, Aging, Addicted by Bert E. Park in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2021Print ISBN

9780813156286, 9780813118536eBook ISBN

9780813185651PART I

Sick Heads and Tall Tales

Few things threaten biographers more than finding themselves on grounds as unfamiliar as disease and its impact on behavior. Emboldened by a fistful of what were considered irrefutable scientific data in the first half of the twentieth century (when biohistory came into vogue on the heels of psychoanalysis and the now disgraced musings of phrenology), they found it expedient to assault their subjects with such diagnoses as defective glands, syphilis, and epilepsy. After all, contemporary medical thought assured them that any one of these conditions, untreated, could dramatically alter personality.

Appreciative reviewers and unwary readers, encountering something both novel and intriguing, passed on what they had read without much reflection and even less understanding. Were one to believe those writers who have ignored more prudent seconds in their own corner, virtually every tyrant has at one time or another let his guard down, only to be rendered punch-drunk by the slings and arrows of pathophysiology. Yet with time and the evolution of medical knowledge, a few discerning critics began to suspect that some “classic” matches between disease and behavior were little more than charades.

Napoleon Bonaparte is a case in point. To explain his mid-life transformation, the voyeur with books to sell began by pummeling below the emperor’s belt at his infested genitals and an unruly case of piles—or changed tactics and jabbed at Napoleon’s seizure-riddled brain. Yet assuming that the defenseless subject could not have been totally irrational and still rule an empire or win a battle, some writers pulled an ill-defined “hormonal imbalance” from the grab bag of diagnoses for the knockout punch. By such sleight-of-hand has the corpse of the Little Corporal grown larger than life.

The same applies to a despot of an earlier time whose girth grew as if to accommodate his self-indulgence; few men in history were said to have matched sex, sport, and suds with Henry VIII. In time, however, the king’s formidable reputation was eclipsed by the very excesses that marked his reign. No one disputes that the years were unkind to Bluff Hal. What is less certain is whether the regal head or tail took a greater beating at the hand of the syphilitic sphirochete while he lived or from the imaginative pathographer long after he died.

Once more sophisticated explorers of the mind came to disdain the medieval belief that disease and peculiar behavior were attributable to moral transgression or divine retribution, they were left to ponder the secular and often competing contributions of neurology and psychology. If the former was initially limited to identifying infestations growing within the brain, the identification of epilepsy some fifty years before the emergence of Freudian psychoanalysis catapulted the concept of a seizure-induced personality into the mainstream of pathography. Few theses have been so liberally exploited, though it is one that all too often smacks of medical reductionism in the hands of imprudent sleuths frantic to uncover pathography’s next Rosetta Stone. I know that from experience: as an older, other person, I now recognize the limitations of having once applied the temporal-lobe-epilepsy thesis to Adolf Hitler. Mark it well: no second opinion is more painful than that which brings one’s own first into question. Whether the same might pertain to the other case studies presented in the final essay remains to be seen. Despite what the skeptic would surely term a hackneyed concept, this thesis deserves a second look with regard to Hitler and other zealots, if only to reexamine one admittedly rare physiologic phenomenon that subsequent psychoanalysts have managed to ignore.

CHAPTER 1

Napoleon Bonaparte: Heads or Tails?

Can the pathographer make head or tail of Napoleon’s perplexing medical history? Despite the attempts of a myriad of imaginative specialists to reduce this Corsican upstart to little more than a walking textbook of disease, even the most skeptical investigators are willing to consider that Napoleon might have won the battle of Waterloo had he not been indisposed; for thrombosed hemorrhoids were said to have diverted the general’s attention during his final curtain call on the stage of European history.1 In that sense, a painful tail wagged what remained of the dog days of Napoleonic France. The more cerebrally inclined believe the causes for his downfall lie elsewhere: whether as a result of an imperial pituitary gland that failed, a brain that occasionally misfired in sporadic bursts of epilepsy, or a psyche warped with Freudian complexes, Napoleon was a psychophysiologic wreck waiting to happen. Yet perhaps the real answer to biohistory’s most popularized enigma may be found in neither the emperor’s head nor his tail but somewhere in the middle—in what physicians of the Victorian era discretely termed the “equatorial zone” of the abdominal cavity.

About Waterloo itself, at least one thing seems certain: Napoleon lost the battle on June 18, 1815, by closing his window of opportunity the day before. Although on June 16 the struggle against the British and Prussians had proved indecisive, a rout of Napoleon’s adversaries on June 17 looked propitious, given the strength of French reserves. Yet as historian Frederick Cartwright has concluded: “It was in those twelve hours from 9:00 P.M. on the 16th to 9:00 A.M. on the 17th that the campaign was lost.”2 What is now known is that Napoleon was uncharacteristically indecisive during that twelve-hour period and lost contact with the Prussians during the morning of the seventeenth. We also know that he was in a great deal of pain. Quite unlike the disciplined warrior of earlier years, Napoleon slept late and confined himself to his tent on that fateful day, losing the advantage in the early morning hours. Why such perplexing behavior?

Dr. William Ober offered an intriguing clue in his essay “Seats of the Mighty.” Napoleon, he says, was suffering yet again from painful hemorrhoids occasioned by long hours in the saddle. He had earlier ridden in a bouncing carriage across the Alps to Paris after his daring escape from Elba, only to endure further the subsequent journey to Waterloo. On June 13, portents of disaster gripped the imperial loins. As the biohistorical critic Arno Karlen so aptly described its implications: “Riding horseback with piles is a fate to be wished on one’s worst enemy.”3 That is precisely the painful position in which pathology placed Napoleon before the decisive conflict with Blücher and Wellington. History tells us that when a leader crosses the Rubicon of his career, what goes on in his head is usually the decisive factor. Yet for French history, what came out of the tail in a very literal sense may have weighed as heavily—and as painfully. From the pathographer’s perspective at least, the future of Napoleon’s empire rested less on his shoulders than on his sensitive and fragile bottom.4

If the emperor’s bulging hemorrhoids obscured a more penetrating look at his behavior through the historical proctoscope, the persevering medical investigator might do well to hang Napoleon in the stirrups of the urologist’s examining table to study his diseased bladder. After his return from Egypt in 1799, he began to suffer from painful and hesitant urination that plagued him until the end of his military career. Victor Hugo recorded that not only did Napoleon ride through the day at Waterloo with “ghastly bladder pain” but that similar symptoms had begun as early as 1800 during the Battle of Marengo, only to recur at Borodino and Dresden during the 1812-13 campaign. Nor did the painful malady ever unleash its grip. In captivity at St. Helena during his last years, Napoleon was often observed leaning his head against a tree, trying in vain to urinate.5

No one knows for sure whether the front or back of Napoleon’s imperiled loins was more of a burden for him at Waterloo. What washes this discussion out of gossip’s gutter and into the mainstream of historical analysis is that his military conduct arguably suffered as a result. Yet were bleeding piles or a shriveled bladder enough to account for a dethroned emperor’s ultimate failure on the battlefield? Hardly so. To argue that Napoleon lost his tactical advantage to the fickle dictates of disease is to ignore those military historians who have already given us good and sufficient reasons for his defeat. Though he may have been in some distress at the time, the weight of the evidence suggests that Wellington’s superior resourcefulness and patience in battlefield command were the decisive factors.

It is one thing for the diagnostician to reduce a set of symptoms to their lowest common denominator; it is quite another to lead the gullible historian down the primrose path of medical reductionism by attributing historical effect to pathologic cause. Still, subsequent revelations will at least risk suggesting that underlying illness did account in large measure for Napoleon’s dramatic change in appearance and behavior—and perhaps even a change in history itself—but not before other myths concerning his health are dispelled and the limits of the medical argument defined.

If civility and common sense are reasons enough to dispense with further speculation about an unruly case of hemorrhoids, greater liberties continue to be taken with Napoleon’s chronically inflamed bladder. His heavily sedimented and painful urinary stream brought to mind two distressing—if undeserved—implications linked to the emperor’s recalcitrant genital hardware. The first was his failure to produce heirs during his marriage to Josephine, leading to the spurious assumption that chronic infection of the urinary tract accounted for his suspected impotency. This theory was dispelled by imperial ejaculates that produced Napoleon II and at least two illegitimate children.6 Reversing their steps to the entrance of that blind alley, a few intrepid gumshoes entered another by suggesting that Napoleon had returned to Josephine from a lengthy military campaign in Egypt with venereal disease. There was much of medical significance in that campaign (revealed below), but syphilis was not a part of it. No credible evidence links Napoleon to that source, despite what some biographers have said.

The tail end of the medical legends that surround Napoleon and other historical figures cannot be told without paying homage to the testicles of the elite, which always seem to weigh so heavily for the Freudian investigator. The heaviest on record, at least by the criterion of literary license, were the testes of Harry S Truman, of whom someone quipped that after his victorious showdown with John L. Lewis in the coal strike of 1946, one could “hear his balls clank” as he walked down the halls of the White House.7 Though fumbling with the genitalia of deceased generals and presidents recalls the naiveté of the phrenologist, who once assumed that greatness could be mapped out by the contour of the skull or the convolutions of the cerebral cortex, Napoleon was not immune to such ribald scrutiny. He was said to have suffered from underdeveloped genitalia (once attributed also to Adolf Hitler) by temerarious genital fixators, smug in their assurance that a small penis is injurious enough to the afflicted’s psyche that he overextends himself to bolster his compromised masculinity. This charge can be dismissed in Napoleon’s case, given the discovery of normal, albeit retracted, genitalia at his autopsy.8

Nor did Napoleon’s drive and ambition wither away in time like his private parts ensconced in an increasingly corpulent groin, as boldly asserted by those who refused to look above the Corsican beltline for explanations of Napoleon’s inactivity and lethargy in his later years.9 Some have even gone so far as to cite Napoleon’s deprived manhood as evidence linking his deterioration to a hormonal deficiency10—which brings matters to a head in a very literal sense.

We are not referring in this instance to Napoleon’s brain; rather, a few pathographers have drawn attention to a small organ at its base (the pituitary gland), which is the control center for hormonal and endocrine balance in the body. A British neurologist was the first to suggest that Napoleon suffered from a deficiency of this master gland, a disease known as Froehlich’s syndrome.11 That surmise was pounced upon by other physicians, one of whom referred to the emperor’s “infantile genitals,”12 while another pronounced him a “pituitary eunuch” on the basis of his corpulence, lethargy, thinning hair, and pudgy hands.13

True, these changes in Napoleon’s physical appearance were universally acknowledged at the relatively young age of thirty-six. Truer still, the renowned Napoleonic self-discipline disappeared as rapidly as did his theretofore insatiable vitality and capacity for work. For one who had always prided himself on burning his candle at both ends, the wax of Napoleon’s genius had clearly begun to melt down. Could his physical and mental decline, at least descriptively consistent with a burned-out pituitary gland, have been responsible? Hence the opening of the door of the bony vault at the base of Napoleon’s skull encasing this tiny organ to the pathographer’s examination—a door that has been forced open despite the absence of a key to fit the Froehlich lock.14

Though Napoleon may have suffered from a relative degree of thyroid deficiency,15 it would represent a quantum leap of imagination to blame the pituitary gland as the cause. An underactive thyroid is certainly a more common condition in the aged than has been previously recognized, but to postulate this in a man of thirty-six defies the law of averages, unless some underlying pathology in the pituitary could account for a hypothyroid state in concert with other hormonal deficiencies. At first glance, the observations of one British physician who had attended Napoleon’s autopsy cannot be dismissed out of hand as incriminating primary data implicating a lack of testosterone. “The pubis much resembled the mons veneris in women,” he recalled. “The muscles of the chest were small, the shoulders narrow, and the hips wide. The penis and testicles were small.”16 In his most imaginative (if not politically motivated) prose, Dr. Walter Henry was depicting an effeminate male with a glandular deficiency. In reality, he was describing a pear-shaped habitus that probably reflected the physical inactivity of Napoleon’s later years. As for the alleged “defective genitals” found at autopsy, allowance must be made for the well-known fact that the penis and scrotum normally contract against the body after death. Moreover, Napoleon had hardly been impotent or infertile, a distinction at variance with persons victimized by Froehlich’s syndrome. Nor is an underactive pituitary gland an evanescent condition. Without drug replacement it remains a pervasive, day-to-day physiologic burden, one hardly consistent with the brief displays of energy, brilliance, and vivacity that characterized the ailing emperor until very near the end.

And what of Napoleon’s alleged short structure? Could this have been due to a lack of growth hormone from the same “failing” pituitary gland? Once again, the imaginative investigator has harnessed a recalcitrant Froehlich steed to a wagonload of unsuppo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction: On Prudence and Skepticism

- Part I. Sick Heads and Tall Tales

- Part II. Brain Failure at the Top: Psychology or Pathology?

- Part III. Drugs and Diplomacy

- Part IV. The Crippled Presidency

- Postscript—or Apologia?

- Notes

- Index