- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book examines the idea of organism in the work of Louis I. Kahn, from the turning point of Rome to the project for Venice. It presents an original interpretation of the work of Kahn during one of the most fruitful periods of his career, when he was working on a particular design method based on an entirely novel way of interacting with the past. Beginning with a meticulous documentation and analysis of Kahn's experiences in the twenty years from 1930 to 1950, the book sheds new light on the relationship between Kahn's work and the modern movement. The arguments are supported by case studies, including that of the Palazzo dei Congressi in Venice based on Kahn's words (like his lessons in Venice at IUA, International University of Art, in 1971) and others as the Trenton Bath House, the Salk Institute (La Jolla), the Kimbell Museum (Fort Worth), the Yale Gallery and the Mellon Center for British Art (New Haven) and more.

Unlike much of the by now well-established literature on Kahn's work, Louis I. Kahn in Rome and Venice suggests that the basic premise of Kahn's invention is the idea of spatial, constructive organism, which explains how he created forms that were inextricably anchored in the past, without imitating any one kind of ancient architecture. The main objective of the book is to explain Kahn's methodology to architects and students, showing how he was able to design an architectural object with the characteristics of the best designed objects: organisms, in which each part contributes, with the whole, to creating "something made of indivisible parts".

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

IV Kahn and Venice. “Places more than buildings”

Venice is the architecture of joy.I love this place, which is all of one piece,where each building collaborates with the others.An architect wanting to design in Venicehas to think in terms of collaboration.Working on the project I thought constantlyabout the buildings I love so much in Venice, asking myselfif they would accept me into their company.

8 The significance of the idea of city

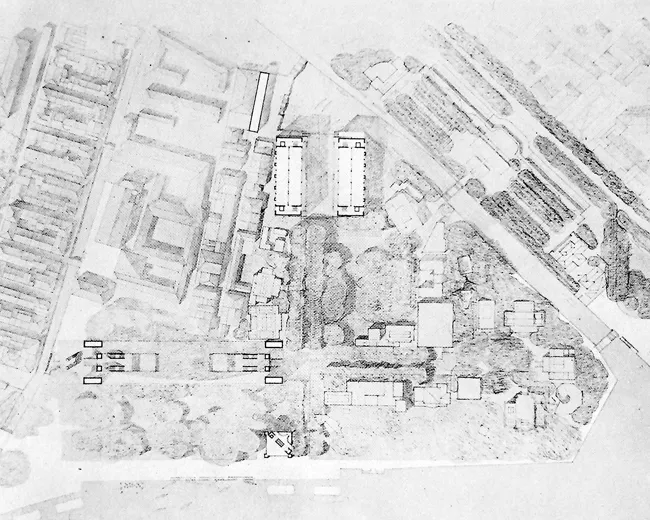

The entire form of Venice – its ideal form, one might say – can be preserved only if the whole of Venice, in its totality of works of art, is maintained and upheld as urbs and as civitas, in every respect and with no reservations.4

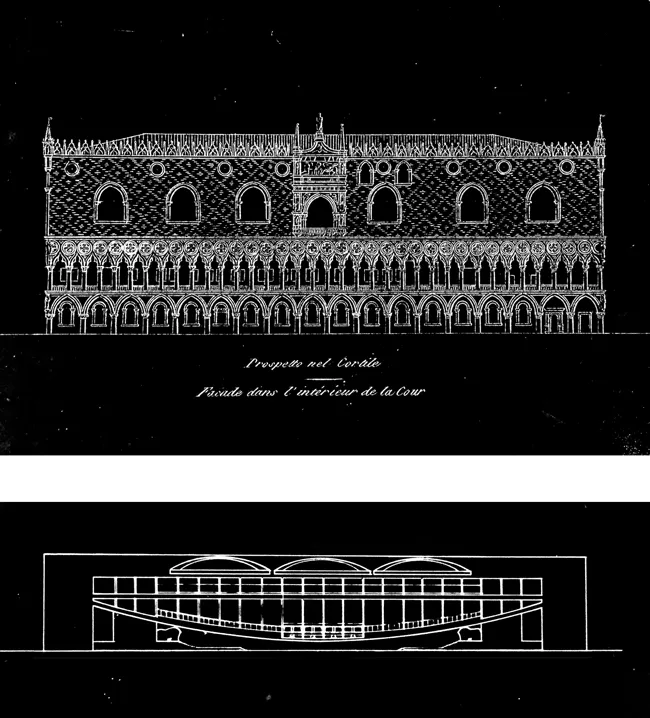

8.1 The design project of the Palazzo dei Congressi, 1968–1969

Day after day, the ancient Venetians invented their lives and their city; the Venetians of today live off their city as if it were an inherited legacy, using it as easily and as least inventively as they can; in other words, they risk consuming it. If they carry on using Venice as an object to show off on certain occasions, they will lose it, no matter what expedient they come up with to bequeath it to future generations; they will lose it as a living organism and therefore able to express itself as a city, and have in exchange a restored monument, lifeless and embalmed, frozen in its final form: a ruin for tourists, which is the exact opposite of what Venice should be.5[…] [A]ny possible technocratic intervention would only compromise the situation in Venice; only by discovering new ways of expressing the spirit of its community can the city achieve a subsequent and corresponding recovery of its proper, formal dimension. […] [T]he island city will thus be the organizing centre and driving force for the greater Venice, the benchmark for a life of harmony and industry.6

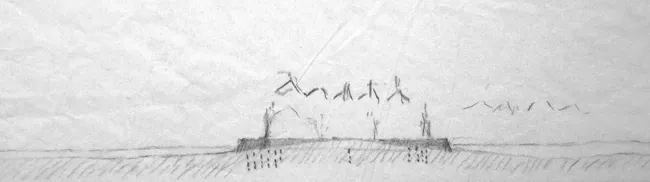

But, we must know in order to make nature help us, because nature is the maker of all things. But man has the vision, the sense, of what nature cannot make without him; he cannot make it without nature, but nature cannot make anything without man (that man wants), therefore, you must know its orders: you must know the order of water, the order of air, the order of spaces, the order of structure, the order of time, the order of construction, the order of materials; man knows intuitively the order of stone, but he must learn the order of concrete, of steel, of plastic, he must not just use it, he must know the order of it.9

There is not city today which is more pointedly an ecological problem than that. There is not. So, therefore, it is, in my opinion first, you see, considering the threat, it’s considered as an ecological problem. Yes. Now, I see Venice, a city in a fecund field which is the whole Lagoon. […] I would like to see the phenomenon of Venice be extended so that all of you know it is Venice. Yes the lagoon, and whatever is built. Yes. It seems to me that there must be an architecture of water. There must be also an architecture of air.10

Now, in thinking small, I didn’t want to take down one of the details of sculpture or stone! Now again, in thinking big, I thought that instead of trying to imitate the charm of the wave of buildings, that I felt, if you were to make a compound (like a very large palazzo of small buildings). A building of simple geometry with a court, and with gardens and passages. That it would not trying anyway to imitate the charming results of increment of building. And this in relation to elevated gardens and… well… and fundamentally an architecture of windows. Yes. That it is not an architecture of walls, but again I don’t mean a glass facade. I was thinking more in a line of the buildings, in… as say in Amsterdam, which try to minimize the pear-shape (like to say the spaces between windows). But the windows, of course, would be entirely Venetian, of course, I don’t mean Amsterdam.13

Plastic architecture, derived from the continuity of forms constructed in long-lasting, massive materials, is the domain of solidarity, where every individual thing is bound to the others and collaborates to the life and unity of the whole; the walls link together spaces and structures in the builder’s one single action.14

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Foreword: Kahn revisited

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- I The critical reception of Kahn in Italy

- II Basic principles

- III Architectural unity in Kahn’s work

- IV Kahn and Venice. “Places more than buildings”

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index