- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Cold Stress

About this book

This book provides an up-to-date, accessible, and comprehensive coverage of human cold stress from principles and theory to practical application.

It defines cold stress and how people respond to it. It describes how to assess a cold environment to predict when discomfort, wind-chill, hypothermia, shivering, frostbite, and other consequences will occur. It also advises on what to do to prevent unacceptable outcomes, including determination and selection of clothing to preserve comfort and health.

The book will be of interest to practitioners and students and anyone involved with fields such as textiles, clothing, and industrial hygiene.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Human Cold Stress 1

Cold

Human cold stress is the continuous and dynamic combined interaction of the effects on a person of variables air temperature, radiant temperature, air velocity and humidity, as well as clothing and activity, that can result in a drop in body temperature. The variables are termed the six basic parameters as fixed representative values are often assumed. It is not determined by one (e.g. air temperature) or a sub-set (e.g. air temperature and wind) of those factors but the combined effect of all six. In water, water temperature and flow will add to cold stress.

The effects of the cold stress can lead to unacceptable cold strain in terms of discomfort, distraction, loss in capacity to perform tasks, reduced health, cold injury and death. This can be caused by lowered body temperature (hypothermia) but is often due to the strain on the body (particularly the heart and in vulnerable people with underlying medical conditions) due to physiological response as well as people simply ‘giving up’.

Being cold is a miserable experience and should not be confused with being in a cold environment which can be exhilarating, stimulating and pleasant. A cold environment is one that has the potential to cause heat loss from the body leading to feeling cold, discomfort and lower body temperatures. Exercise and clothing can keep the body warm in a cold environment and provide thermal satisfaction and pleasure. Toner and McArdle (1988). Young (1988) cites Leblanc (1975) ‘man in the cold is not necessarily a cold man’.

There are three main human responses to cold stress. These are to increase heat production: by exercise, increased muscle tone (thermogenesis) and shivering; reduce heat loss: using clothing and physiological responses that lower skin temperature; and, most importantly, behavioural changes: that reduce the level of cold stress (move to a warmer area, seek or create shelter), reduce exposed body surface area (change posture), increase activity and clothing insulation and many more depending upon culture, customs and opportunities available. ‘Adaptive opportunity’ that ‘allows’ behavioural responses is an important characteristic of the environment and should be a fundamental part of environmental design. It could be regarded as a seventh basic ‘parameter’ and is an essential consideration in any modern assessment of human cold stress.

A final point about cold is that it has no meaning in physics other than to say that a body of lower temperature (less average kinetic energy) is often said to be colder than one of higher temperature. Being cold is a biological and psychological phenomenon not experienced by inanimate objects or fluids. A brass monkey does not feel cold despite the inconvenient result of lowering its temperature.

Psycho-Physiological Thermoregulation

Feeling cold and uncomfortable is a major drive for human response usually in terms of behaviour. Comfort (or discomfort) can be regarded as a significant ‘controlled variable’ in human thermoregulation (Parsons, 2020). When uncomfortable we respond in an attempt to become comfortable. When comfortable there is no drive for change and we are satisfied with the thermal environment. When heat loss is significant we sacrifice comfort for survival and control internal body temperature to an optimum level of around 37°C (people are homeotherms). This is part of homeostasis where humans control their internal environment to optimum levels. As body temperatures fall, physiological responses include vasoconstriction (preventing warm blood reaching the skin) to lower skin temperatures (reduce heat loss) particularly in the feet and hands with associated discomfort and drive for behavioural response and shivering, which increases heat production. The environment is dynamic and this psycho-physiological response is a continuous interaction between the body and the environment.

Water

Water is essential to life (over 50% of the body is water and it is a significant part of our environment) and for the temperature range on Earth we experience water in its states as liquid, vapour and solid (ice, snow, etc.) and its conversion from one state to another. Water influences heat transfer from the body in each of these three states. Evaporation of water vapour (at a rate of the latent heat of vaporization (2.45 × 106 J kg−1 or 41W of sweat loss at 1g/min (McIntyre, 1980)), causes a chill when cold, and heat loss by breathing. Liquid water turns to water vapour during evaporation and also causes heat loss by conduction (particularly if the body is immersed in water – and also convection if the water is moving). Liquid water also reduces the insulation of clothing. Water is at its highest density at 4 °C and when water freezes (at 0 °C (or −0.5 °C in cells and −2 °C for sea water)) it releases the latent heat of fusion (3.33 × 105 J kg−1). It also expands so that when water in cells freezes it damages the cell contents and causes irreversible damage to the cell wall (frostbite).

We should note that when water changes from vapour to liquid, in condensation, the latent heat of vaporization is released, just as it is absorbed from the body when liquid sweat changes from liquid to vapour. When water changes from solid ice to liquid the latent heat of fusion is absorbed and released when freezing from liquid to ice. It takes heat to break the molecular bonds when water changes form, so energy is required but there is no change in temperature. This is relevant to heat transfer for people in cold environments.

Water evaporated to vapour and transferred to the inside of impermeable clothing will condense on the inside surface of the clothing and heat will be conducted to the outside thereby releasing a small amount of heat from the body by sweating even when wearing impermeable clothing. The build-up of liquid water will reduce the insulation of the clothing. Collins (1983) and Golden and Tipton (2002) however note that to evaporate 1 litre of water a person would lose up to 675 W, whereas if they wore an impermeable outer-cover (wind break) even with wet clothing it would take only 35 W to heat water from 4°C to a comfortable skin temperature at 33°C in one hour.

A layer of warm water will exist around a warm body in cold water. This will rise as it is less dense than the cold water so heat will be lost by natural convection but it will give insulation to the body in still water when compared with moving water which will reduce or eliminate this layer of warmer water so that the body surface rapidly becomes that of water temperature. This is a familiar experience for those used to taking cool baths and explains why immersion in cold flowing water is more dangerous than immersion in cold still water with restricted body movement.

Wind

For a warm body in air there is also a temperature gradient between the skin and clothing surface of a person and the lower temperature in the cooler air of the environment. There is a layer of warmer air therefore around the body and as it is less dense than the cold air outside; it rises at a rate proportional to the temperature difference. This is called natural convection and it can be significant in a cold environment, particularly from the exposed skin of the head and hands. Air flows upwards across the surface of the body and there is a plume of warmer air above the person. Air movement across the body caused by body motion or wind (or both) interferes with the air layer such that the body surface tends towards environmental temperature and hence clothing and skin temperature become close to air temperature due to the forced convection of the wind. The skin then feels cold and the effect is called wind chill. If the body is wet then evaporation will cool the body even further and the chilling effect will be much greater.

Feeling Cold

There are separate hot and cold sensors across the skin of the body, more in some places than others (Gerrett et al, 2015). They are nerve endings (no specialised sensor has been identified) that respond to temperature and particularly the rate of change of temperature. Cold sensors have a firing frequency from 2 Hz at 15°C, peaking at 9 Hz at 30°C, reducing to 0 at 37°C with an ‘erroneous’ paradoxical discharge above 45°C (Dodt and Zotterman,1952). There is adaptation if temperatures do not change and temperature and rate of change of temperature provide a firing rate that is interpreted along with other factors to provide a feeling of cold. They can also imply wetness as the body does not have sensors that can detect wetness directly (Filingeri et al., 2014).

Fanger (1970) (see also ISO 7730, 2005) describes a Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) index that predicts the mean sensation of a large group of people on a scale +3, hot; +2, warm +1, slightly warm; 0, neutral; −1, slightly cool; −2, cool; −3, cold from an equation that includes values of the six basic parameters. For optimum (comfort = neutral) conditions the body must be in heat balance and skin temperatures (and sweat rates) must be at comfortable levels. That is for steady-state conditions. In changing environments (including rapid or transient changes) rate of change of skin temperature is important. Parsons (2020) emphasizes the importance of changes in air velocity as it influences the insulation provided by the air layer at the skin. So exposed skin temperature tends towards air temperature in wind.

Draughts cause a feeling of cold and can provide discomfort and a stiffness of muscles if prolonged. The percentage of people dissatisfied due to a draught (when they otherwise have neutral sensation) can be predicted as a Draught Rating (Risk) DR = (34-ta)(v-0,05)0.62(0.37Tu+3.14) for air temperature ta (°C), v is local mean air velocity (ms−1) and Tu is the local air turbulence, the standard deviation of the local air velocity divided by its mean (%), (ISO 7730, 2005; Olesen, 1985). Turbulence is significant as it reduces the insulation of the air layer more effectively than laminar air. When a person is already cold in terms of the whole body, the draught rating is expected to be more severe than when the person is otherwise comfortable as the draught rating merges into wind chill. A radiant ‘draught’ occurs when there is asymmetric radiation for example when sitting next to a cold window on a train (Underwood and Parsons, 2005).

Feeling cold is a consequence of physiological regulation as vasoconstriction ‘attempts’ to preserve heat but lowers skin temperature particularly in the hands and feet. The drive for behavioural response is very strong and taken as a whole provides a framework for the consideration of human cold stress.

Feelings of thermal discomfort and physiological responses can be predicted by a calculation based upon the heat transfer between the body and the environment. This is suggested as a first step in any assessment of human response to the environment and is termed the thermal audit (Parsons, 1992). Interpretation of the thermal audit can contribute to the assessment of human cold stress, prediction of thermal strain and provide a basis for environmental and system design. It is presented in the following chapters.

The Body Heat Equation 2

The Thermal Audit in the Cold

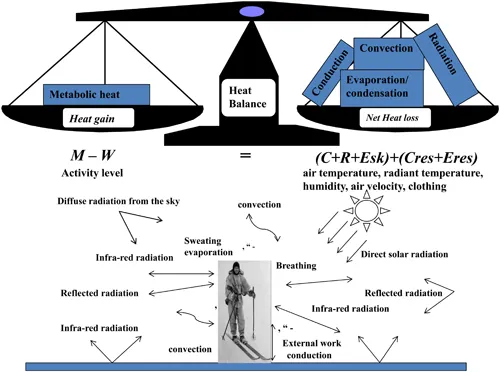

The first law of thermodynamics ensures that we can account for heat into and out of the body without loss and hence conduct a thermal audit (Parsons, 2014). The human disposition as a homeotherm is to attempt to maintain a ‘constant’ internal body temperature at around 37°C. For any object to maintain constant temperature the heat inputs to that object must balance with the heat outputs from the object. If a person has a net heat gain then their body temperature will rise and if a there is a net heat loss it will fall. For a constant temperature then the body must be in heat balance. If we derive equations that quantify avenues of heat inputs to the body and heat losses from the body we can set up a body heat equation and for constant temperature we can describe the body heat balance equation (see Figure 2.1).

An important starting point is that energy for the body is generated in the cells by the metabolism of food. The total amount of energy produced is termed the metabolic free energy production in Joules or metabolic rate (M) in Joules per second or Watts (often normalised to Watts per square metre of body surface area (Wm−2)). Much of that metabolic rate is produced as heat (H = M-W) which is transferred from the body to the environment. The remainder is used for mechanical work (W). Human thermoregulation can be considered to be about the relative preservation and dispersion of metabolic heat to control body temperature.

During cold we must preserve sufficient heat to maintain body temperature; however, when exercising in the cold, excess heat must be lost (through clothing) to the environment. This is driven by the differences between skin (and clothing) surface temperatures and air temperature as well as differences in radiant temperatures and the differences in water vapour concentration at the skin and in the environment (related to humidity). It is also influenced by air velocity across the body and the thermal properties of clothing (e.g. insulation and vapour permeability). Any heat balance equation and any consideration of human response to cold must therefore consider air temperature, radiant temperature, air velocity, humidity, clothing and activity (to estimate metabolic heat production). These are termed the six basic parameters (see Chapters 4, 5 and 9).

The four mechanisms of heat transfer between the body and the environment are conduction (K), convection (C), radiation (R) and evaporation (E). The heat balance equation is where by convention, M and W are heat gains and K, C, R and E are heat losses. A negative heat loss is a heat gain (including condensat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Author Biography

- 1 Human Cold Stress

- 2 The Body Heat Equation

- 3 Human Thermoregulation in the Cold

- 4 Human Metabolic Heat in the Cold

- 5 Clothing in the Cold

- 6 Selection of Clothing for Cold Environments

- 7 Wind Chill

- 8 Required Clothing Insulation

- 9 A Computer Model of Human Response to Cold including Torso, Limbs, Head, Hands and Feet

- 10 Human Performance and Productivity in the Cold

- 11 Diverse Cold Environments

- 12 Diverse Populations in the Cold

- 13 Hypothermia, Freezing and Non-Freezing Cold Injuries and Death

- 14 Skin Contact with Cold Surfaces

- 15 Practical Assessment of Cold Environments

- Appendix 1: VBA Code for the Thermoregulatory Loop in the Modified Stolwijk and Hardy Model

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Cold Stress by Ken Parsons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.