- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1975, and written by an authority on Scottish music, this book traces the evolution of the bagpipe whilst also narrating the fortunes of the 'Great Highland Bagpipe' itself. Exploring history and archaeology of civilizations as far removed from the Scottish Highlands as Egypt and Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome this book offers a unique full-length history of one of the world's most interesting and ancient musical instruments. Appendices list the bagpipes of other countries and the materials used in the instrument's manufacture as well as a comprehensive bibliography.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bagpipe by Francis Collinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Scottish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter one

Antiquity

The earliest pipes

If we examine the general principle of the bagpipe as it is today, we may reduce it, in its simplest terms, to an inflatable bag of skin which provides under pressure of the arm a stream of air to one, two or more reed-sounded pipes. Usually one of these plays the melody, and the others the accompaniment. Such accompaniment is most often in the form of a continuous fixed drone; though there are numerous instances among the different species of bagpipe of the accompaniment taking the form of a variable drone or simple harmony part, or even of a rudimentary counterpoint to the melody. In one instance, indeed, that of the Cheremiss bagpipe in Russia, it is observed by Anthony Baines in his book Bagpipes (p. 49) that the players of it achieve all these three elements of accompaniment together, in ‘a rich mixture of drone, harmony and true polyphony’.

This is not the place to describe in detail the construction and technique of the modern bagpipe. The reader is referred to chapter 1 of Anthony Baines’s Bagpipes for a full description and to the glossary of names of the component parts at the back of this book. But by looking here at the general principle of the bagpipe, we may see that the invention of the bag did not in itself constitute a new musical instrument, but merely an addition to an existing one. This was the more ancient reed-sounded single- or double-pipe blown by the mouth. In the double-pipes, one of the pipes probably sounded the melody and the other the accompaniment, just as with the bag-blown instrument we know.

These reed-pipes are very ancient indeed. They are known to have been in use for nearly three thousand years before the bag was invented - and that was certainly not later than the first century B.C., as we shall see.

The reed

The basic means of producing the sound in the pipes, the reed, is a discovery belonging to prehistory - to that far distant moment in time when some unnamed youth found that by pinching flat the end of a straw or plant-stalk and blowing into it with compressed lips, he could produce a more or less musical sound. He had stumbled upon the principle of the double reed, so called from the fact that the squeezing of the end of the straw naturally produces two flattened surfaces or ‘blades’ at the squeezed part. These two blades vibrate with the pressure of the breath and produce the sound.

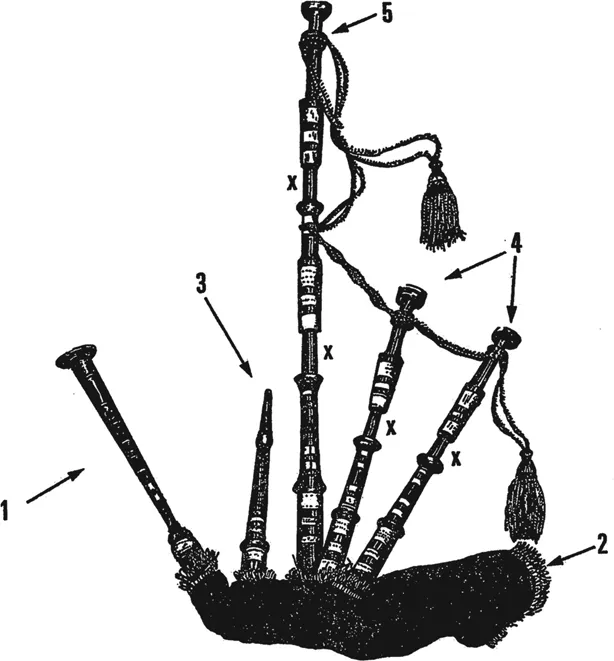

- (1) The chanter

- (2) The bag, with cloth cover (often of tartan)

- (3) The blow-pipe (‘blow-stick’) or insufflation tube

- (4) The tenor drones

- (5) The bass drone XXX tuning slides for the drones

Such a simple discovery as this could have occurred (and probably did occur) in any number of places in any part of the world independently. It is as well to state this at once, for though it is possible to say where the earliest specimens of the reed-sounded pipe or pipes have been found, namely in Babylonia and ancient Egypt, such finds may have depended as much on natural conditions for their preservation through time, as on any priority of construction or invention in the countries of their discovery.

For this reason, it is impossible to dogmatize upon any theory of evolution of the reed-pipes based upon geography. One can only say that reed-sounded pipes have been known to be in use in certain countries of the East at a certain period of time. One cannot say that they had not already been invented and in use elsewhere. We know very little, for instance, about the music or musical instruments of the early Celtic races before about A.D. 500, though they must have had music long before that.

So much for the hypothetical discovery of the double reed. The process of construction of the single reed was slightly more complicated. For this a knife was necessary. It was found that if a tongue was cut a little way along the length of the straw, either towards or away from one of the knots or natural nodes, and the player inserted the straw into his mouth to the full length of the cut and blew, a musical sound could be produced. With such fragile material as a corn-stalk the single reed would be less liable to become clogged or sodden with the moisture of the mouth than would the crushed end of the straw of the double reed. It would be more dependable and easily controlled.

Such an imagined picture of the discovery of the principle of the reed may be thought to be over-fanciful; but in fact musical pipes of earlier millennia have been found in the excavated tombs of Egypt having just such reeds of straw as we have described, sometimes with unused straws beside them for their replacement. The reeds have been found in position in the pipes, with spare straws in the protective cases in which the pipes were found.* These will be discussed in detail.

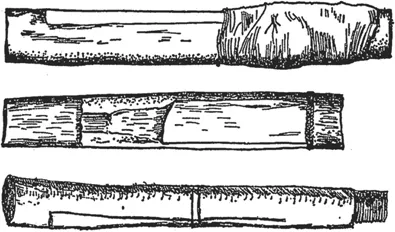

When the tongue or ‘blade’ of the single reed is cut towards the knot or node of the straw or cane, it is known as an ‘up-cut’ reed. When the blade is cut away from the node, the reed is called ‘down-cut’.

The double reed made of cane is the type used in the chanter of the Scottish bagpipe. It is the type also used in the instruments of the oboe and bassoon families of the symphony orchestra. The single reed is the type used in the drones of the Scottish bagpipe. It is also to be found, in more sophisticated form, in the orchestral clarinet.

It would have been convenient for the purpose of easy identification if one could have referred to the double reed as a ‘chanter reed’ and the single as a ‘drone reed’, as in the Scottish bagpipe; but in dealing with the general history of the instrument this will not do, for in the pipes of other countries, both ancient and modern, we find that either type of reed may be found in use for chanter or drone according to its particular country and species. The well-known musicologist, the late Curt Sachs, refers to the pipes of whatever age simply as ‘oboes’ or ‘clarinets’ according to their type of reed (double or single, respectively) which for clarity has a good deal to recommend it.*

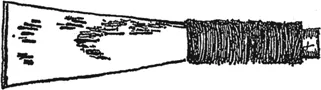

- (a) single ‘beating’ reed, down-cut

- (b) single beating reed, up-out (both (a) and (b) are enlarged to show detail)

- (c) reed of bass drone of Scottish Highland bag-pipe (down-cut)

The chanter

It seems logical to suppose that the use of a single pipe, playing the melody only, must have come before the twin or double pipes which, with the possibility of a harmony part on the second pipe, appear to represent an enormous advance in musical resource and sophistication. The curious fact is, however, that the earliest known specimens of the reed-pipe yet discovered, and even the earliest depictions of it upon the stone or terra cotta steles and inscriptions of Egypt and the middle-east, are all of the double pipe. There is one exception which will be described in its place. This means that the addition of the second pipe, presumably for accompanying the melody, must have been very early indeed. A number of such double-pipes have been discovered in ancient Egyptian tombs, whose age is to be reckoned in thousands of years. These are on view in the museums of Cairo1 and elsewhere.

There was however a curious intermediate stage between the single pipe playing melody only and the addition of a second pipe for accompaniment. This was the use of two duplicate pipes closely bound together, with the fingerholes corresponding in position in each pipe, and therefore both intended to play the melody simultaneously. Each finger covered the corresponding holes in both pipes and produced the same note from each pipe at every finger position.

One may well ask what musical advantage there could have been in adding a second pipe for the sole purpose of doubling the melody. There were two possible reasons. One was that two pipes played together in unison would obviously produce twice the volume of sound that a single pipe would - on the principle of the old proverb that ‘two pigs under a gate make more noise than one pig’. It is also possible, by putting one pipe ever so slightly out of tune with the other, to produce a ‘beat’ or wave effect in the sound. This can be not unattractive, as the modern organ-builder has found and developed in the organ stop known as ‘waves of the sea’ or unda maris.

The two pipes, voicing the same note in this fashion, were sometimes contained within a single tube possessing twin bores throughout its length. Each bore had its own reed and fingerholes. The fingerholes, corresponding in position and lying close together in pairs, could as a general rule only be played by the same finger covering both holes at once. This species, found largely in central Europe, notably in Croatia (see Baines, Bagpipes, p. 71), is known as the diple (i.e. double) pipe. It may be seen in a Scottish example, in the exquisitely made stock and horn in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland in Edinburgh.

The typical and perhaps clearest example of the parallel mouth-blown pipes are the ancient Egyptian zummara, with corresponding fingerholes in each pipe. Zummaras of obvious antiquity are displayed in the plates of the illustrated catalogue of the Cairo Museum; but probably because of the less meticulous documentation of exhibits at the time of their discovery, their period is stated as ‘unknown’; Curt Sachs in his History of Musical Instruments mentions a pair of zummaras, or ‘double clarinets’ as he calls them, excavated from Egyptian tombs of the first century B.C., though he does not give a reference. He has also (ibid., p. 92) recognized parallel pipes on a relief known to be as early as 2700 B.C.

These parallel pipes seem to have been played with the single reed, the reed roughly similar to the drone-reed of the Scottish bagpipe. Unfortunately the reed has not been found in any of the specimens of antiquity in the Cairo Museum, but the zummara of ancient times corresponds so closely with the modern one in its general design that we can fairly safely assume that the type of reed was the same.* The reeds of the modern zummara are of cane, like the pipes themselves, and are ‘up-cut’. In the Cairo Museum also however is an instrument almost identical with the zummara but with the reeds down-cut; this is listed under the name of mashourah.2

The pipes of the common modern zummara are usually unornamented, though the several coils of fine black string binding them together form a characteristic ornamentation of its own sort. The catalogue describes a pair of zummaras of which, to quote, ‘Les tubes sont décorés de quelques decoratives [sic] à dessins simples se composant soit de traits parallèles soit de signes géométriques.’

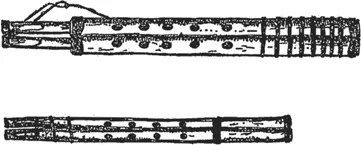

- (a) Zummarah or zummara (modern Egyptian); note upcut reeds fr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Dedication Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter one Antiquity

- Chapter two Britain after the Romans

- Chapter three The Great Highland bagpipe

- Appendix I Materials

- Appendix II Two indentures of apprenticeship

- Appendix III The bagpipes of other countries

- Glossary Bagpipe components and other terms connected with musical reed-pipes

- References

- Bibliography

- Index