- 434 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geography of the U.S.S.R

About this book

Originally published in 1964, and extensively illustrated with figures and charts, this volume gives an overview of both physical and human geography of the former USSR. The role that the geography of the country has played in shaping historical events and political forces is discussed, as is its role in the economy of the Soviet Union. The geography is examined by topics and regional differences explained within this framework. The book looks at some of the major problems posed by geographical conditions and how they have been tackled and as far as data allows, the success or failure of measures has been assessed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geography of the U.S.S.R by R. E. H. Mellor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1The Physical Environment of Russia

DOI: 10.4324/9781003172048-1

ONE of the most difficult and yet fundamental problems to a proper understanding of Soviet society and affairs is to appreciate in real terms the geographical environment in which they exist. This cannot be measured in the units of time and distance commonly employed in Western Europe, a continental peninsula with a small and highly diverse regional personality. The two striking features of the Soviet world are its territorial immensity, so that despite its diversity the units which comprise it are so large as to be almost incomprehensible to the usual scales of measure in the Western European mind; and the inhospitality of the environment arising principally from climatic factors associated with its northerly position in a vast land mass, often omitted in our assessment of Russia. The atlas distribution maps give a picture of great regional diversity completely lost to the traveller across the vast, monotonously dull and relatively unchanging countryside. When in the miniscule cosmos of Western Europe, a day's journey takes the traveller across several markedly different regions, in Russia such a journey will see hardly a change in the landscape and little difference in the climate. Such changelessness is accentuated by the standardization and regimentation of Soviet life. The changes are nevertheless present in a subtle and almost imperceptible form. Russia contains both arctic and temperate desert, dense forest and barren grasslands; the wide and virtually flat immensity of the West Siberian Lowland contrasts with the high, jagged, snow-clad peaks of Caucasia; from the well-settled farming countryside of the Ukraine, with its big villages and busy country towns, the traveller can go to the sparsely-inhabited and sometimes imperfectly explored wilderness of Eastern Siberia.

The territorial vastness of the U.S.S.R. is illustrated better by saying that it is some three times the area of the U.S.A. and ninety times that of the United Kingdom than by quoting figures. An area of 8.6 million square miles, it covers one-sixth of the habitable land surface of the globe, stretching across Northern Asia and Eastern Europe, so occupying the core of the

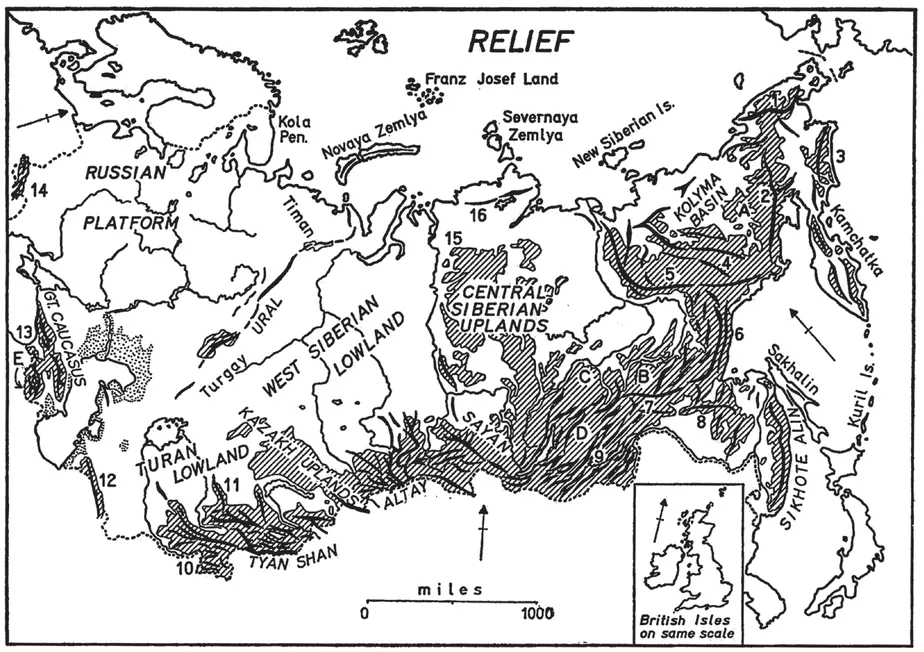

FIG. I Relief. Land over 1,500 feet shaded and main trends of mountain ranges shown. Mountains: 1 Anadyr, a Gydan (Kolyma), 3 Koryak, 4 Cherskiy, 5 Verkhoyansk, 6 Dzhugdzhur, 7 Stanovoy, 8 Dzhagdy, 9 Yablonovyy, 10 Pamir, 11 Kara Tau, 12 Kopet Dag, 13 Little Caucasus, 14 Carpathians, 15 Putoran, 16 Byrranga (Taymyr). Plateaus: A Yukagir, B Aldan, C Patom, DVitim, eEArmenian. Atlas Mira, Moscow, 1954.

Eurasian continent. So great is it in longitudinal extent that the day begins eleven hours earlier in the east than in the west: when people in Vladivostok get up, Muscovites are going to bed; in fact, these two towns are farther apart than London and New York. The most northerly point of the Soviet mainland lies well within the Arctic Circle at Gape Chelyuskin, 770 44' N.: it is more telling to note that Moscow lies 250 miles further north than London and Leningrad is in the same latitude as the Shetland Islands. Almost half the country is affected by permafrost, a typical phenomenon of northerly continental latitudes, and has a winter lasting more than six months. These cold northern influences penetrate deep into the heart of Asia, across the low northern coasts and great plains which stretch to the foot of the high mountains of Central Asia and Mongolia. Yet it is a land of great climatic contrasts: in Soviet Central Asia there are deserts with intensely hot, arid summers but bitterly cold winters north of Bukhara and Fergana on the latitude of Madrid. Sheltered by the Great Caucasus, rich, humid lowlands lie around the Kolkhiz Lowland. The strong climatic rhythm of a long cold winter followed by a wet spring with great floods and then a short, warm, or even hot summer whose dust is laid in the brief, invigorating autumn, dominates the yearly cycle of Russian life.

Although Russia appears to hold a commanding central position — the nodality of a 'heartland' in the Eurasian landmass — and although its frontiers extend for over 36,000 miles, it is nevertheless surprisingly isolated by geography as well as by choice from neighbouring countries. The long southern land frontier in Transcaucasia and in Central Asia, as well as in Southern Siberia as far as the upper reaches of the Amur, is formed by rough upland and mountain country, broken by relatively few gaps or crossed by few easy passes, which rises mostly out of sparsely-inhabited steppe or forest. In the middle and lower reaches of the Amur and Ussuri, the frontier is guarded by wide marshes. Even Russia's long frontage on the Arctic and Pacific Oceans is frozen throughout most of its length for long periods each winter, while access to the Atlantic Ocean is through narrow, peripheral seas of the Baltic and Black Sea-Mediterranean, easily blocked by hostile powers. Yet in the air age, Russia lies astride many of the potentially busiest great circle routes from Europe to South-east Asia and from North America to Asia.

Does Russia belong to Asia or to Europe? It has been customary to conceive the Russian lands as divided into a European and an Asiatic part, though the boundaries between them have been seen differently by various authorities, and the division is still used by the Russians themselves.1 Although these terms may be useful for regional description, it is clear that the Soviet Union can only be regarded as an integral whole, and at the same time its characteristics can be described as neither fully European nor fully Asiatic: it is Eurasian, for its life and behaviour in every aspect are an amalgam moulded in the distinctive geographical and ideological environment of the Soviet state. The bulk of the population and the greater part of the nation's economic activity is concentrated in a narrow wedge of fertile black earth lands and deciduous forest which tapers eastwards into Siberia. While the centre of gravity of Soviet life tends to shift eastwards, it is unlikely that it will ever lie predominantly in Siberia or Central Asia.

STRUCTURE AND RELIEF

Fundamentally, Russia is composed of two large, ancient platforms, partly exposed and partly covered to varying depths by later deposits. On the west is the Russian Platform, and to the east the Central Siberian Platform. Between them lie the Hercynian structures of the Ural and the lowlands of Western Siberia and Central Asia. The southern and eastern periphery of the country is formed by a vast amphitheatre of mountains and uplands of more recent origin, though containing uplifted blocks of older eroded orogenic systems. The ancient platforms of crystalline rocks, such as granite and gneiss, were subjected to intense movement in Pre-Cambrian times; but later they were levelled by erosion, while fracturing and movement raised or lowered large blocks of country. Over great distances, these ancient materials are overlain by more recent sediments, frequently almost horizontal and undisturbed. In European Russia, the ancient crystalline base appears only in the shields of Karelia, a part of the Fenno-Scandian shield, and in Azov-Podolia. In Siberia, the basal structure surfaces in the Aldan and Anabar shields, although the uplifted block of Central Siberia has been deeply dissected by river erosion. Closely associated tectonically with these shields are the folds of the Caledonian orogeny in Southern Siberia.

FIG. 2 Structure. Based on Shatskiy, N., Tectonic Map, 1: 5 M, Moscow, 1956, as simplified by Saushkin, Y., in Voprosy Geografii, 47, Moscow, 1959. Also Atlas SSSR, Moscow, 1962, p1. 72-73.

The Palaeozoic materials, which form a broad belt between the two great platforms, were folded in Hercynian times. The folded materials outcrop in the low ranges of the Ural and in the Kazakh Uplands, which also contains some Caledonian elements. Novaya Zemlya also belongs to this group. Hercynian orogenic belts can also be found in the Altay and in the ranges of Central Asia, where they have been greatly modified by the Tertiary alpine orogeny. Epi-Hercynian platforms deeply covered by later materials form the base of the great lowlands of Western Siberia and Turan.

Mesozoic structural elements are found mostly in Eastern Siberia, including the great geosyncline in which the middle and lower Lena flows. They also include the structures associated with the Kolyma Median Mass. Kainozoic folds are divided by the Russians into two groups: the southern group (Carpathians, Crimean mountains, Caucasus, Pamirs, and Kopet Dag) of Tethys, and the eastern group of Pacific folds, including Kamchatka, Sakhalin, the Dzhugdzhur and Gydan mountains, as well as the Kuril Islands and the coastal ranges of the Sikhote Alin. The alpine movements caused structural modifications in Southern Siberia and the older Central Asian ranges, such as the formation of the many distinctive and economically important tectonic basins. The aftermath of these movements is left in the seismic and volcanic phenomena found here.

The ancient platforms form lowlands in European Russia and low but intensely dissected plateau blocks in Central Siberia. The roots of the older mountain systems are now found as low mountains of generally rounded relief, like the Ural, or as tablelands spattered by residual hills, such as the Kazakh melko sopochnik, or in other instances, lowlands covered by considerable depths of later deposits. The younger mountain belts have a topography of high mountain ranges and high plateaus, frequently forming serious obstacles to inter-regional movement. In the Kainozoic mountains there is great conformity between tectonic structure and morphology, which has been established over a considerable period of time; and likewise, in belts of Mesozoic folding, the relationship is less contrasted, probably as the result of extensive denudation during the Kainozoic period. The exposed roots of the ancient mountains are particularly rich in minerals, though important resources are also found in the sedimentary materials covering the platforms and lying in piedmont depressions of younger mountain ranges.2

Russia is, however, a country of immense rolling plains: about half the country lies below 600 feet. The European Russian Plain, an eastwards extension of the North European Plain, covers about a quarter of the whole country. The smaller West Siberian Lowland exceeds it, however, in monotony of relief. Between these two plains, the low ranges of the Ural with their easy passes do not form a barrier, and yet assume an importance in Russian thought greater than their true nature warrants. They have become the conventionally accepted divide between Europe and Asia. East of the Yenisey, uplands predominate, though they are seldom above 3,000 feet. The southern borders are formed by high mountains, including the highest elevations in the Soviet Union, in the Pamir-Alay mountains, where Communism and Lenin Peaks rise to 24,590 feet and 23,363 feet respectively. High mountain ranges also separate Central Siberia from the Pacific coast: the recently discovered Pobeda Mountain reaches 10,322 feet, while Klyuchevskaya Sopka in Kamchatka exceeds 15,000 feet. In contrast, the Caspian Depression lies below mean sea level; the present surface of the Caspian is 92 feet below sea level. The bottom of of the Karagiye Depression on the Mangyshlak Peninsula is 434 feet below sea level. Another great depression of the graben type is occupied by Lake Baykal, the deepest lake in the world.

Differing erosional processes have contributed to the formation of relief in Russia. During the Quaternary period, ice sheets from Scandinavia and the northern Ural spread over northern and central European Russia; Ural ice and some from the Taymyr Peninsula also covered the northern part of the West Siberian Lowland. The resultant landscapes are contrasted between the intensive ice erosion on the Karelian shield and the masses of outwash materials, moraines and other phenomena further south. Traces of widespread glaciation remain in Northeastern Siberia and parts of Central Siberia, though development of icecaps in a dry continental environment was hindered by the lack of moisture. The contemporary mountain glaciation of the mountains of Southern Siberia (the Altay and the Sayan), of Central Asia, particularly the high Pamir, and the Caucasus, is a remnant of shrunken Quaternary glaciers and icefields. The sequence of glacial advances and milder interglacial periods in Russia, however, cannot always be readily correlated with that established in Western Europe. Arctic islands still contain large glaciers and ice sheets, while over almost half the country the occurrence of permanently frozen ground exercises considerable influence upon landscape; for example, by solifluction in slope formation or the arresting of karst formation by freezing.

Throughout European Russia and in modified form in the permanently frozen ground of Siberia, normal 'humid' subaerial denudation is characteristic. In Central Asia, however, arid erosional processes are active in an area of inland drainage, where large sandy and clayey deserts exist. Evidence indicates that these areas were once more intensively desiccated, but that in the recent geological past they have also undergone moister periods marked by remains of old river beds, dried out lakes and broad alluvial deposits. There are also remains of former arid continental weathering in the inselberg (melkosopochnik) landscapes of the Trans-Uralian Peneplain and the Kazakh Uplands.

The deflation processes commonly associated with arid weathering have deposited around the fringe a belt of loessic materials best developed in the wide piedmont zone along the base of the dry foothills of the Central Asian mountains. The loessic deposits of southern European Russia appear to have originated in an ephemeral arid phase during the glacial epoch, either by deflation during a dry interglacial, or by wind-borne material carried from outwash deserts around the ice sheets' periphery. This may also explain some of the Asiatic deposits. These soft, friable materials have already been extensively eroded into gullies, an attack accelerated by man's destruction of the natural vegetation and by poor husbandry.

THE MAJOR PHYSICAL REGIONS 3

The most densely peopled parts of the Soviet Union and the core of the Russian nation lie in the European Russian Plain, the largest of the lowlands, extending some 1,100 miles from the northern arctic coast of the Barents and White Seas to the almost mediter-ranean conditions of the Black Sea. From the foothills of the Ural it extends westwards for 1,500 miles to merge with the glacial plains of Poland. The Plain rests on a base of ancient crystalline rocks, much faulted, fractured and down-warped, overlain by almost horizontal and little-disturbed younger sediments. Only in the shields of Karelia and the southern Ukrainian Podolsk-Azov uplands do the ancient rocks appear at the surface. Elsewhere they are brought near the surface by fracturing and warping, which exercises some influence upon the relief of the plain in a series of broad depressions between gently undulating plateaus. Where the younger strata have been eroded away from the older, Pre-Cambrian basement, low scarps occur — in the Silurian scarp of the Glint in Estonia and in some of the drift-mantled surfaces to the south of Leningrad — while the Donets Heights represent up-warped Carboniferous rocks of the Donets Basin resting against the Podolsk-Azov shield. The highest surfaces seldom rise above 1,000 feet and between the higher parts of the interfluvial plateaus and the bottoms of the broad valleys there is only 300-400 feet difference in elevation, so that over the vast distances of the plain the slope is indeed very gentle and the continuity of the undulating surface is seldom broken, except along the steep bluffs above the right banks of rivers and by deep erosion gullies in the southern steppe. The depressions are occupied by meandering, sluggish rivers or swamp. Settlement tends to seek higher and drier elevations, though frequently the highest surfaces are avoided, particularly in the steppe, for they are exposed to the bitter winter winds blowing from the heart of Siberia. Despite the seeming uniformity and featureless appearance of the plain, small changes in elevation or slight breaks of slope can have important military, political, or economic significance. The contrasts in the landscapes and the settlement and economic patterns of the plain are conditioned, however, more by the broad latitudinal climatic and soil-vegetation belts than by relief and physical form.

Although accurately made within the limits of scale, an atlas map can give a misleading impression of the relief of the European Russian Plain, for distances are extremely great compared to the variation in elevation over the plain. The relief features are the result of the denudation of the mantle of softer deposits which cover the crystalline base, although in some places, dislocation and fracturing of this basement has exercised an influence on the broader pattern of relief. Everywhere the action of water is evident: in the steep right banks of the rivers and their low left or 'meadow' banks, as well as in the shaping of the superficial covering of Quaternary glacial de...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents Page

- INTRODUCTION Page

- 1. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT OF RUSSIA

- 2. CLIMATE, SOILS, AND VEGETATION

- 3. THE GROWTH OF THE RUSSIAN STATE AND THE RUSSIAN CONTRIBUTION TO GEOGRAPHICAL EXPLORATION

- 4. POPULATION DISTRIBUTION AND ETHNIC COMPOSITION

- 5. TOWN AND VILLAGE AND TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION IN THE SOVIET UNION

- 6. GEOGRAPHY OF AGRICULTURE

- 7. FUEL AND MINERAL RESOURCES

- 8. INDUSTRIAL GEOGRAPHY

- 9. GEOGRAPHY OF TRANSPORT

- APPENDIX

- GLOSSARY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX