![]()

![]()

PART ONE

The Setting

![]()

Chapter 1

Dilemma

French institutions and foreign policy in the interwar years generally received much more criticism than sympathy from British ministers. Up or down, France always seemed to be in the wrong. ‘France is full of the idea that she is going to control, overwhelm and keep under Germany … It is only France who could give us trouble now’, Lloyd George told his Cabinet on 30 June 1920.1 Eighteen years later all the talk in the British government was about the defects of the French who had ‘no Government, no aeroplanes and no guts’.2 Even the fall of France and passing of the Third Republic was greeted with some satisfaction. The third French Republic’, wrote Henry Channon, R. A. Butler’s Private Secretary, on 10 July 1940, ‘has ceased to exist and I don’t care; it was graft-ridden, incompetent, Communistic and corrupt and had outlived its day’.3

Such verdicts showed little appreciation of the limitations which circumstances placed on French statesmen. The shrinking of French power was as well-established as the decline of British influence. French predominance in the 1920s masked a deep, underlying predicament. France, like Great Britain, was not a power from her intrinsic strength, as the United States and the Soviet Union were fast becoming between the two world wars. Many of the trials and tribulations which plagued France were caused by her endeavour to sustain a role for which she was unfitted. The First World War overtaxed her strength and the peace that followed confirmed her weakness.

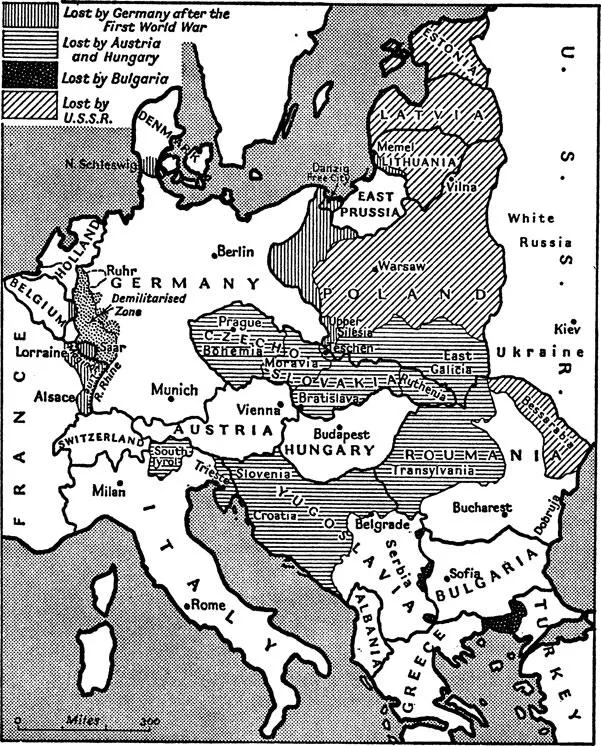

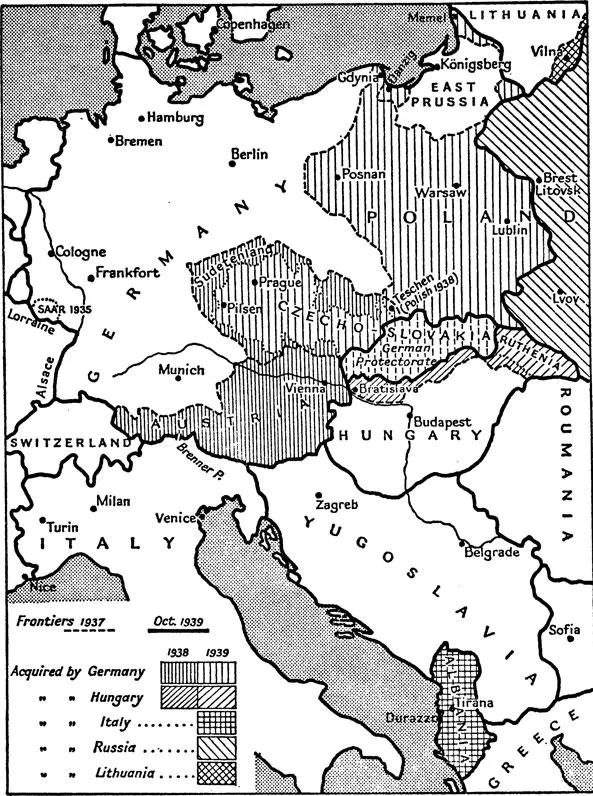

The constraints of circumstance with which French leaders had to contend after 1918 were of two kinds: external pressures imposed by the changing international situation, and internal restrictions stemming from the inherent weaknesses and peculiarities of French society. The chief external constraint was the destruction of the balance of power between 1870 and 1914. By her victory of 1870 Germany replaced France as the leading continental power and much of the international history of the next forty years was a direct result of the consequences of this supremacy. However until the 1880s there was an equilibrium in the sense that no one of the five great powers — Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Great Britain and Russia — could hope to vanquish all the others combined. By 1914, as the First World War showed, Germany, with only a little help from Austria-Hungary, was able to take on a coalition of four great powers — France, Great Britain, Russia—and, from 1915, Italy.

The war of 1914-18, by completing the destruction of the international system, greatly increased the limitations of French power. France owed her victory to the intervention of the United States in 1917, but American withdrawal from Europe after 1919 left a vacuum which a resurgent Germany would sooner or later fill. The survival of Germany as a great power and the withdrawal of the United States marked a fundamental deterioration of France’s position. There were no counterbalancing allies. The Russian revolution of 1917 deprived France of a major ally. The Franco-Soviet pact of May 1935 never compensated for the loss of the Franco-Russian military alliance of 1894. Although diplomatic relations with Russia were restored in 1924, the Bolshevik revolution left a legacy of mistrust. The antipathy of French conservatives for the new Soviet regime was compounded by the Bolshevik repudiation of Tsarist debts. Eighty per cent of Russia’s pre-1914 state debt was owed to Frenchmen and there was hardly a middle class family which did not hold some Russian bonds.

In the race towards industrialization and military strength France was held back by the poverty of her natural resources. In 1850 Great Britain and France were the only industrial powers of any consequence; by 1880 Germany had outstripped France in coal, iron and steel output and France had slipped to fourth place in the production of these materials. Her coal output in 1913 was 41 million tons, compared with Germany’s 279 million tons and Britain’s 292 million tons. By 1935-39 the disparity between France and Germany was even more marked: France was producing 47 million tons of coal against Germany’s total of 351 millions. In 1938 the French government estimated that in war France would have to import 48 million tons of fuel, including 23 million tons of coal. Of course, Germany herself was overshadowed before 1914 by the meteoric rise of the United States. By 1914 the United States was producing 474 million tons of coal. Moreover French industries were, on the whole, comparatively small and major industries were confined to five departments in the north, the edges of the Massif Centrale, and a few cities such as Paris, Lyons and Marseilles.

Equally as important as France’s industrial weakness was her demographic inferiority. In an age of conscript armies the key test of a great power was the number of men she could put into the field. In 1850 France with a population of 35.5 millions was still the most populous country in western Europe. In 1880 she had 15.7 per cent of the European population; in 1900 she had only 9.7 per cent. The rate of increase of the French people between 1880 and 1910 was 5 per cent, for Germany it was 43 per cent, and for Britain 26 per cent. In 1940 France’s total population was 41.9 millions; this compared with 45.9 in Great Britain, 43.8 in Italy, and with 69.8 in Germany. The fall in French natality had established itself in the early years of the nineteenth century. Given the lack of population growth, the manpower losses of the war of 1914-18 were disastrous. Of the belligerents, France suffered most in relation to her active male population, losing over 10 per cent of her active males; this compared to 9.8 per cent in Germany, and 5.1 per cent in Great Britain.4

The First World War, by testing the fundamental economic resources of the belligerents, demonstrated the inability of France to maintain herself unaided in a major conflict. France was dependent for manufactures and armaments on imports, especially coal. Geography imposed an extra handicap since much of her heavy industry was concentrated in the northern and eastern departments, close to the frontier with Germany. German occupation of large areas of northern France represented 53 per cent of coal production, 64 per cent of iron, 62 per cent of steel, and 60 per cent of cotton and other manufactures. Agriculture was also seriously affected. The territory occupied from 1914 to 1918 accounted for one fifth of the country’s wheat supply.

The alliance with Great Britain, indispensable though it was during the war, offered no security for the future. The entente had withstood the test of war but British Ministers shunned a peacetime military pact and a full military alliance was not re-created until the spring of 1939. All that the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, could promise France in 1938 was two divisions, with the proviso that their despatch would be subject to the decision of the government of the day. Great Britain had her own problems in the postwar decade. She was no longer the self-confident nation of 1914. A sense of diminished power and a growing preoccupation with Imperial interests strengthened the determination of British statesmen to steer clear of continental entanglements.

The changing relationship between Europe and other continents was another adverse circumstance for France’s leadership. In a world dominated by the European powers, France had appeared to be stronger than she was. In the Far East, Japan emerged as a great power of formidable naval strength. The war of 1914-18 speeded up the political and economic forces which were undermining Europe’s primacy. One indicator of change was the loss of French overseas investments. In 1914, French investments abroad totalled 8,686 millions of United States dollars, by 1938 the sum had shrunk to 3,859 millions. Half of the French portfolio was sold to pay for the war but, unlike the British who rebuilt their foreign investments, the French allowed their holdings to decline.

Another external restriction on France’s freedom was the onset of the Great Depression. The effects of the world economic crisis did more to undermine French power than the material losses of the First World War. Without the Depression, the economic recovery of the 1920s might have been maintained. The chief effect of the Depression was to bring to the surface the latent tensions and weaknesses in political and economic life. The timing of the crisis was decisive. As social and economic strife engulfed France, Germany began rearming and the conjunction of foreign and domestic perils presented the political leadership with well-nigh insoluble problems.

In 1932 the major industrial nations were in the trough of the Depression but France did not experience the worst of the crisis until the mid-1930s — by which date Great Britain, Germany and the United States were showing strong signs of recovery. While her competitors recovered France remained in the doldrums and did not show any evidence of renewal until 1939. Between 1929 and 1938 industrial production increased by 20% in Great Britain and 16% in Germany, while in France in the same period it fell by 24%. In terms of unemployment France was not as hard hit as Germany and Great Britain. Unemployment in France never totalled more than half a million but the protracted stagnation was extremely demoralising. Despite the poor economic performance from 1932 to 1938, the end of the decade brought a glimmer of light. Between October 1938 and June 1939 industrial production returned for the first time to the level of 1928. This economic upswing, equalling the rate of growth of the 1920s, came too late in the day to be of any real help. However the renewed vigour of French diplomacy in the spring and early summer owed much to the gold reserves amassed by Paul Reynaud, Minister of Finance.5

In addition to these pressures France’s rulers were cramped by a number of internal handicaps. The financial burden of the First World War and material devastation caused by the fighting imposed a powerful constraint. The damage was immense. Ten départements had been occupied or laid waste. German troops carted away industrial equipment and economic life had to be restarted virtually de novo. Also, there was the double burden of paying both for the war and for the cost of raising France from the ruins. This was a mammoth task, coming so soon after the strain of the pre-war armaments race. The weight of armaments had fallen heavily on France and she had set aside for defence nearly the same proportion of her national income as Germany had done. The cost of the war was met almost wholly by borrowing. French insistence on the payment of reparations has sometimes been seen as heartless legalism. In reality, reparations, as the French Foreign Minister, Aristide Briand, reminded British Ministers, were a necessity since his country faced ‘ruin and bankruptcy’.6

The war, by aggravating underlying defects in French society, contributed to the decline of France as a great power. Without the war, the archaic fiscal system, practically unchanged since 1789, might have held together longer. In the event the cost of the war brought about its collapse. Unlike Great Britain and Germany, who adopted a modern system of direct taxation in the nineteenth century, France did not accept the principle of such a tax until 1914 and income tax was not introduced until 1920. Consequently very little revenue was raised by direct taxation and it was estimated that while 55 milliards of francs were spent on the war in 1918, only 7 milliards of this sum were raised in taxes. With the advent of peace Germany was expected to pay for the war and French opinion was in no mood to welcome a comprehensive scheme of direct taxation.

All the belligerents were confronted with the problem of inflation and the phenomenon was particularly bewildering for the French who had come to consider the stability of the franc de germinal of 1803 as part of the natural order. During the war, the value of the franc had been maintained by Anglo-American support and when this was withdrawn in 1919 its value fell rapidly. The depreciation of an hitherto stable currency, coupled with the problems of adjustment to a peacetime economy, sharpened social and economic distress. By 1920 the prices of 1914 had quadrupled, though the value of real wages declined. Economic mobilisation and the need to establish new centres of industry behind the front accelerated the long-term drift of population from the country to the towns. The influx of labour brought new strains and stresses, especially in housing. The fiscal system added to the difficulties. Although the principle of a general income-tax was approved in 1914, its implementation was delayed until 1920. The new tax created considerable injustices and inequalities, which fell largely on the lower pa...