1.2 A Brief Review of Certain “Aspects” of Aspects

Standard theory recursive PS rules of the sort postulated in Aspects (and earlier) provided a revolutionary solution to the long-standing paradox of discrete infinity: while the human brain is finite, the generative capacity of an I-language is infinite. Taking this as the core “creative” property of human knowledge of syntax, it was Chomsky’s postulation of recursive PS rules that formally solved what had previously seemed paradoxical, namely “infinite use of finite means” (Humboldt’s term, as Chomsky notes). More generally Chomsky resurrected abandoned 17th-century ideas regarding the mind, and centrally contributed to the modern-day birth of the cognitive sciences, by noting the legitimacy of the postulation of abstract (non-material) concepts in normal (including, of course, even physical) modern science, hence its permissibility, in fact necessity, in (previously, and still by many condemned) mentalistic theories of the brain.

Recursive PS rules provided an explicit representation of knowledge of linguistic structure – “the basic principle” in current terms – and accounted for the “creative aspect of language use.” A recursive structure-building mechanism is necessary for any adequate theory of I-language. But, given the commitment to explanation, important questions emerged regarding the phrase structure component of Aspects, some of which we are fully appreciating only now, some 50 years later. There are two questions we focus on here, involving the nature of the mother node (i.e. projection) and the nature of the empty symbol delta.3

One central explanatory question that arises with Aspects’ conception of phrase structure and PS rules more generally is: “Why do we find that humans develop these particular (constructions-specific or category-specific) rules, and not any of an infinite number of other PS rules, or other types of rules?” Consider a PS rule like (1).

- VP → V NP

Why exactly is there a VP on the left side of the arrow? Why more specifically is the mother labeled VP (and not, say, NP, or some other category or, for that matter, some non-category)? Is the label of the higher category stipulated, or does it follow from some deeper principle of generative systems, or perhaps from an even more general principle not specific to the human language faculty? We might even ask, why is there a label at all? Indeed Collins (2002) proposed the elimination of labels, and Seely (2006) sought to deduce labelessness from the derivational theory of relations (Epstein et al. 1998, Epstein and Seely 2006). Since labels are not merged, they are in no relation, hence are equivalently absent from PS representations.

In Aspects, PS rules were essentially unconstrained, anything could be rewritten as anything, and thus the existence and categorial status of mother labels were stipulated. Thus, for example, there was a “headless” rule like (2).4

- S → NP VP

In (2), the mother node S is not a projection of (i.e. it is categorially unrelated to) its daughters. So, why do we find such headless phrases as S, while the major lexical categories seem to have heads, e.g. V in VP, and N in NP?

Another issue that arose involves a particular innovation of Aspects, namely, the postulation of the empty symbol delta Δ:5

[S]uppose that (for uniformity of specification of transformational rules) we add the convention that in the categorical component, there is a rule A → Δ for each lexical category A, where Δ is a fixed “dummy symbol.” The rules of the categorical component will now generate Phrase-markers of strings consisting of various occurrences of Δ (marking the positions of lexical categories) and grammatical formatives.6

(p. 122)

Thus, delta would appear in the (simplified) deep phrase marker associated with passive,7

- [S [NP ∆ ] was arrested [NP the man]]

Raising of the object NP would involve the substitution of that object NP for the delta subject NP, yielding:

- [S [NP the man] was arrested [NP (the man)]]

↑________________________|

In effect, the delta is an empty and non-branching maximal projection, in this case an NP, and it has a purely formal status.

Note that both the mother (the S in (3)) and delta nodes of Aspects involve, at least in one sense, “look ahead”; they are telic, anticipating transformation that will take place. And this in turn results, in part, from the “top down” conception of phrase structure and from the particular model of grammar assumed in Aspects (in which (3) is postulated since S → NP VP and in which semantic interpretation is at the Deep Structure (DS) level (see Katz and Postal 1964)).

Aspects appealed to “top down” PS rules of the sort in (1) and (2). But as pointed out by Chomsky (1995b), attributing the insight to Jan Koster,8 PS rules of this sort, where the mother node is projected, involve, at least in one sense, “look ahead.” The mother node, the label VP of, say, VP → V NP, is telic in the sense that it indicates the categories generated by the syntax that will be relevant to the interpretive components, PF and LF. Put another way, the DS in (3) in fact encodes the categorial structure of what the Surface Structure (SS) will be. That is, if (structure preserving) delta substitution is required, then the NP subject of S is already present at DS, “awaiting” the obligatory arrival of the man. This encoding of SS in DS threatens the concept of level itself, suggesting that levels are in some sense intertwined, or non-existent (as was later postulated in Chomsky 1993, Brody 1995, Chomsky 2000, Epstein et al. 1998, Uriagereka 1999).

Since in Aspects the initial level of representation, namely DS, fed into the semantic component, and since objects (presumably) required a label for semantic interpretation, it was necessary that labels be encoded as soon as possible, and hence encoded in the structures that served as input to semantics. Furthermore, since SS fed the Phonological Component, and since PF also (presumably) required labels, then the mother nodes needed to be present also at the last stage of a derivation.

Projections were needed, then, at both the initial (DS) and final (SS) levels, and were represented throughout the derivation. PS rules, projecting labels – including NP delta projected from no lexical head N,9 and the S-mother of NP delta, which is not a projection of NP delta, as in (3) above – served precisely the job of providing “sentential level” projection from the outset of the derivation (the theory being a theory of sentence-structure).

The delta is similarly “anticipatory.” Recall a case like (3), in which a subject NP is already present structurally even before it is filled lexically, and this subject NP, since the mother S is already present, has no option of itself projecting; the mother S is already predetermined.

So, recursive PS rules of Aspects provided an empirically motivated, profound answer to a paradox solving the problem of discrete infinity. But, the nature of projection and of the empty symbol delta employed in Aspects raised a number of important questions, involving: projection, the nature of the lexicon, the relation between the lexicon and syntax, delta as a lexical item, the intertwining of levels, “look ahead” the inviolability of S → NP VP, and semantic interpretation at DS.

1.3 X-Bar Theory: The Elimination of PS Rules

X-bar theory represented a major development in the history of phrase structure.10 Rather than unconstrained, stipulated, and ultimately non-explanatory PS rules, the X-bar template imposed tight restrictions on what counts as “humanly possible phrase structure representation.” X-bar theory sought to eliminate PS rules, leaving only the general X-bar-format as part of UG.

X-bar theory pushed endocentricity to its logical conclusion: since some categories seemed to be endocentric, like for example the lexical categories mentioned above (VP, NP, etc.), then, to eliminate unexplained asymmetries, it was assumed that all categories, including functional categories, are endocentric.11 Thus, a PS rule like (2) is excluded; it must be reduced to the X-bar template and thus must be “headed.”

Another major development within X-bar theory was that linear order was removed from the PS component; X-bar projections represented structure but not the linear order of elements within the structure. Standard PS rules simultaneously defined two relations, dominance and precedence, and therefore the application of a single PS rule could not (in retrospect) be a primitive operation since two relations, not one, are created. X-bar theory takes an important step in reducing the two relations to one, and it does so by eliminating linear order, which is a property of PF and (by hypothesis) not a property of LF. Thus, the theory came to express that “Syntax is not word order!” since word order is phonological. This disentangling of “dominance” (in hindsight, a misleading misnomer) and precedence, along with explaining their existence as subservient to the interfaces (dominance for semantics, precedence for phonology), was a profound step in the development of the standard strong minimalist thesis.12

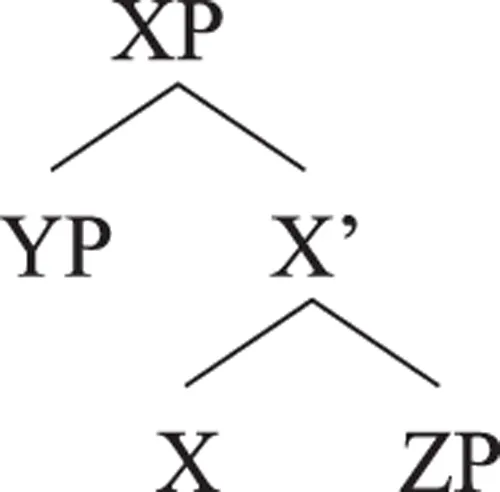

In X-bar theory, the mother is predetermined. Assuming binary branching, if X is non-maximal, its mother will be the category of X. If X is maximal, its mother will be the category of X’s sister. Consider the following tree representation (ignoring order)

In (5), X and X’ are non-maximal13 and hence themselves project. YP is maximal and hence its mother is the category of YP’s sister (in this case X). The same holds for ZP. Projection from a head (i.e. endocentricity), and the syntactic representation of projection are taken to be central concepts of X-bar theory, defining two core relations (spec-head and head-complement).

What about the delta introduced in Aspects? It too implicitly remains in the X-bar schema. Under X-bar theory, the landing site of movement is often called SPEC, but SPEC is in effect a cover-term for delta as well. So, we could say delta was still assumed for movement under X-bar theory, i.e. X-bar was a constraint on transformationally derived structures in which projection is determined by X-bar schemata.14 So, the moving category has no chance to project – the mother of the mover “landing in” SPEC is by definition not the mover.

X-bar theory thus raised a new set of questions – again, following the Chomskyan ...