A work of literature is considered a “classic” when, long after it was written, readers continue to read it. A famous example is Sophocles’s dramatic telling of the story of Oedipus. This is so much a classic that one does not need to have read Sophocles, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, or Freud to know something of the story. Most people recognize in themselves the truth told in this ancient Greek drama: that human beings are affected deeply by extreme feelings of love and hate for their parents.

In most versions of the story, Oedipus loves his mother too much. Without knowing what he is doing or who the people involved really are, Oedipus kills his father and marries his mother. He rules his land with Jocasta, his mother-wife and queen. When a plague threatens the kingdom, Oedipus learns that his domain can be saved only if his father’s murder is avenged—and that he himself is the murderer! He blinds himself and goes into exile. Oedipus’s actual blindness represents his deeper blindness to the effects of his desires on his behavior. His fate is tragically determined not because he had forbidden feelings of love and aggression for his parents but because he acted on them without knowing what he was doing. This story is a classic because people find in it some sort of standard for normal, if confusing, human experience. In literature, a writing is classic because it still serves as a useful reference or meaningful model for stories people tell of their own lives.

Hence, a period of historical time is considered classical because people still refer back to it in order to say things about what is going on in their time. Generally speaking, classical ages engender a greater number of classical writings for the obvious reason that literatures convey the delicacies of their social times. Thus, in our day, when people refer to the Oedipus story, they usually have in mind Freud’s version, which still conveys much of the drama of the modern world affecting people today. The Oedipus story figured prominently in one of Freud’s classic writings, The Interpretation of Dreams, which was published in 1899. In this book, Freud made one of his most fundamental claims about dreams just after retelling the Oedipus story. Dreams, he explained, are always distorted stories of what the dreamer really wishes or feels. They can thus serve “to prevent the generation of anxiety or other forms of distressing affect.”

Freud’s telling of the Oedipus myth is a subject of controversy today because it is taken as a case in point for the feminist criticism that most classical writings in the social and human sciences systematically excluded and distorted women’s reality. They did. In this case, Freud distorted reality by his preposterous inference from the Oedipal symptoms he believed he saw in his patients to the claim that the major drama of early life is the little boy’s desire to make love to his mother. Little girls were left out of this story, the crucial formative drama of early life. They were said to be driven by the trivial desire of envy for the visible instrument of true human development, the boy’s penis. The feminist critique is to the point, but it does not destroy the classic status of Freud’s writings. Feminists are among those who still find much else of interest in his ideas.

Social Theory’s Classical Age: New Beginnings—Then Confusion in a Changing World

When social worlds change, people who live in them often discover a new and different world to which they must adjust. When this happens, initial attempts to come to terms with new global realities usually borrow from the past what once seemed to work in order to invent fresh ideas that might serve well enough in the new dispensation. Some work. Some do not.

Times like these are called conjunctures—which is to say, historical moments when different kinds of time come together to change the way history is lived. It was Fernand Braudel (1902–1985), the French historian, who distinguished historical conjunctures from the two other salient temporal orders. These were, first, what he called long enduring time, or the geologic and geographic aspects of any given region, and, second, the time of specific historical events, or event-history. Braudel’s most famous book was The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. The title tells the tale of his theory of historical times. The Mediterranean Sea and its region served as the long enduring geological and geographical time around and on which the deep history of events from the Greeks and Romans down to Phillip II of Spain came to be, made their histories, then fell away.

The Mediterranean world is another matter. Phillip (1527–1598) was the dominant political figure in Europe after 1500 when, for the greater part of that century, he was the ruler not only of Portugal and Spain and England but also of the Provinces of the Netherlands and the Duchy of Milan. Yet, soon after Philip died, the Iberian kingdoms declined to be succeeded by the Dutch as the core power of the global world system. These were the events for which the Age of Philip II serves as a convenient token. Philip II was the dominant figure of the Age, but the Age comprised a good many historical events.

Therefore, the conjuncture itself was more than the reign of Philip II. It included the structural shift from a Mediterranean world to an Atlantic world and beyond to the beginning of true geographical globalization. This new world began in large part after Gutenberg invented the moveable type press in 1450 which, by 1500, made literacy and reading common skills. Before then, literacy was enjoyed only by priests and elite members of Court. This in turn led to the Protestant Reformation that Max Weber argued, in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904–05), was the source of a radically future-oriented and individualistic practical ethic he called the spirit of capitalism. Protestant culture required that adherents read the sacred text and think for themselves—as a result, in time modern people became independent individuals. In other words, this conjuncture spelt the end of the traditional, backward-looking, medieval culture that choked the region for a good millennium after the Fall of Rome in 410 CE.

All of this was set against the long enduring geological geography of seas, mountains, and settled lands blessed with a temperate climate and an expansive number of safe harbors from which its ships could eventually set sail across the Atlantic, then to the wider world. The historical events before, during, and after Philip II defined the Mediterranean world that was intruded upon by the conjuncture of the 1500s when that world changed dramatically. The new world that slowly emerged just before and after 1500 was the beginning of the Modern Age. Many tend to imagine that the world we live in today is straightforwardly modern. Others suppose it is somehow postmodern. In either case, since 1500, human affairs on earth have changed in many ways without, however, resorting to the dark days of the medieval world. Among those changes, the Enlightenment philosophies in the late 1600s and 1700s set down the cultural terms that made the modern world and its social theories possible.

The Age of Enlightenment, like the Age of Philip II, was itself a conjuncture of sorts. It was an age of many different aspects, each of which could be considered conjunctural. For one example, the Enlightenment gave rise to modern sciences. Michael Foucault, in The Order of Things (1966), persuasively demonstrated that the late 1700s and early 1800s marked the radical shift away from metaphysical, formal, and medieval scientific categories that had little to say about social things. The Enlightenment undercut these traditional analytic categories in favor of philosophies that allowed for theories of the social which is by its nature resistant to metaphysical thinking. Thus was laid the groundwork for the emergence of sciences of modern medical practice, penal practices, economic sciences, and political theories that, in turn, paved the way for the emergence late in the 1800s of social theories as we know them.

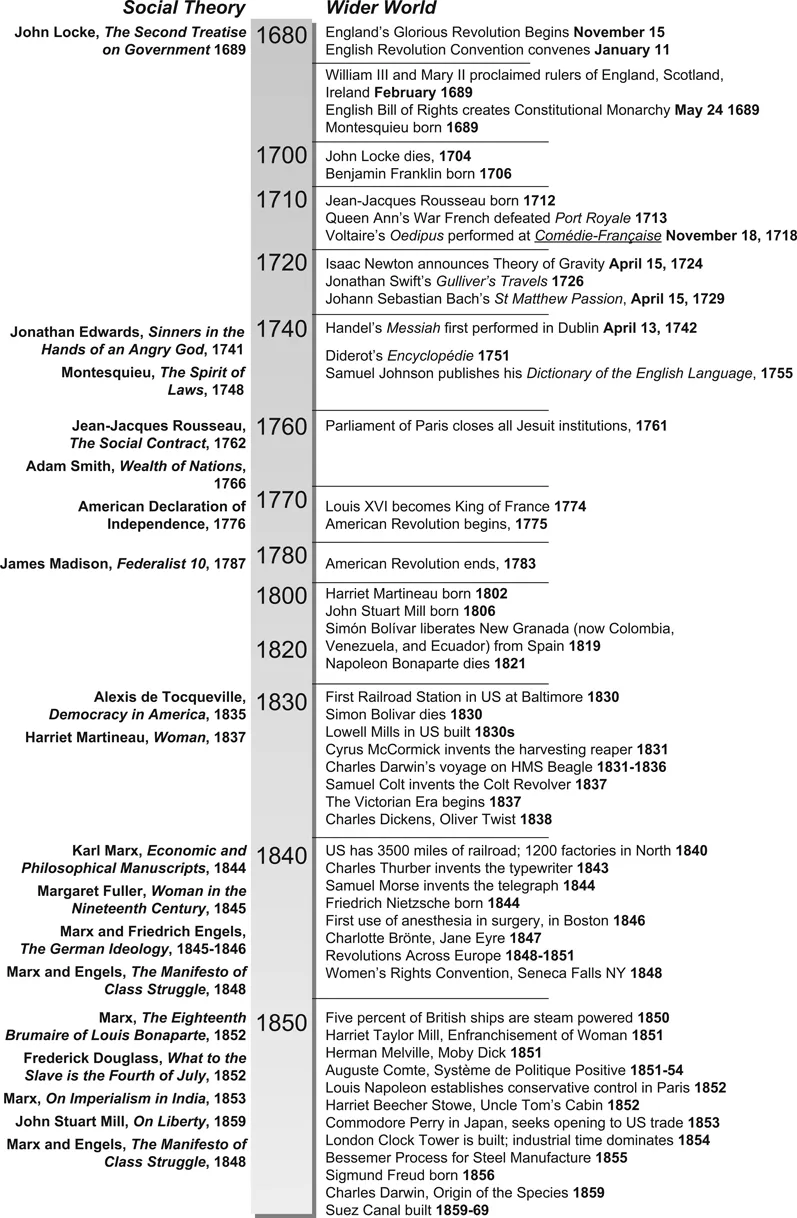

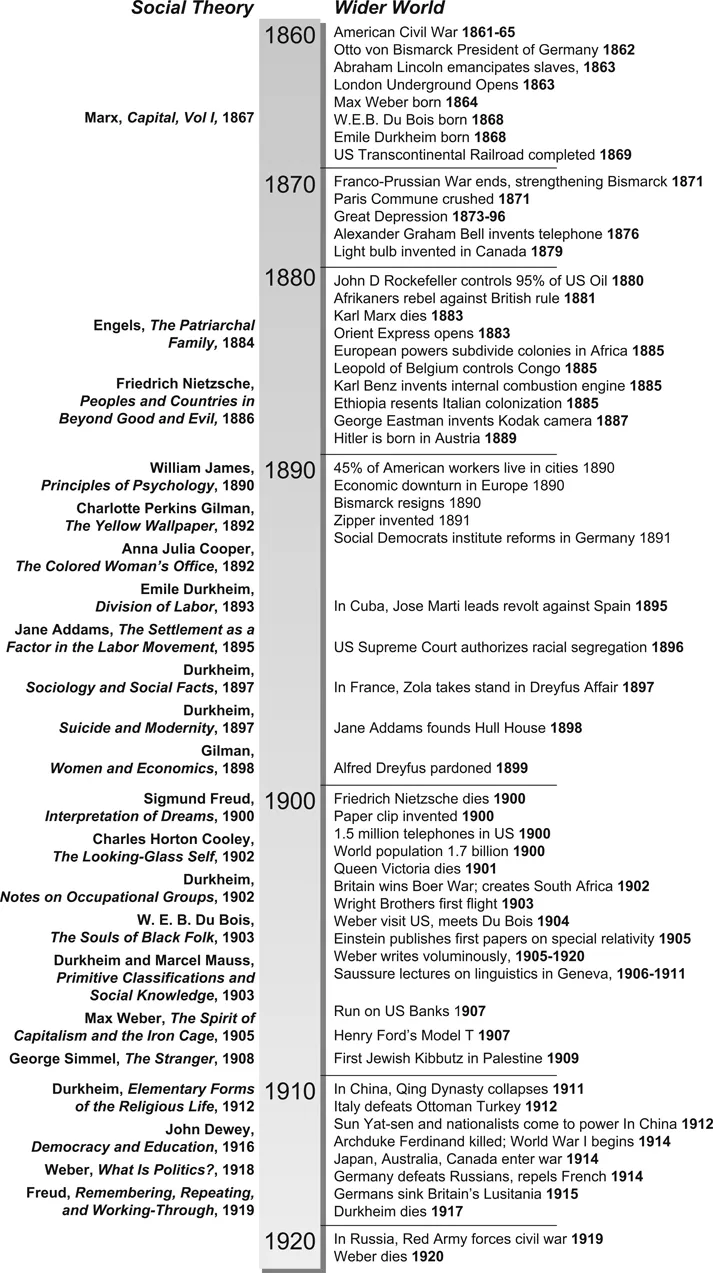

Eric Hobsbawm, the British historian, in three of his most famous books, defined the historical moments of what he called the long nineteenth century—The Age of Revolution: 1789–1848, The Age of Capital: 1848–1875, and The Age of Empire, 1875–1914. Hobsbawm’s dating of his three ages should not suggest that these were discrete moments so much as what might be called a diffuse conjuncture that the Enlightenment made possible—from the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 when the modern nation-state first came to be to the Great War of 1914 that spelled the end of premodern empires like the Ottoman and Astro-Hungarian. These sub-conjunctural moments suggested the idea of a long nineteenth century from 1774–75 and the American Revolution and the French Revolution in 1789, through the rise of industrial capitalism in the mid-1800s, to the Gilded Age late and the growth of urban life late the 1800s, to the end of traditional empires early in the War of 1914.

Across this long march from Enlightenment to urban modernity, the new sciences generated methods that made agriculture more efficient, which reduced the need for field labor, which led to the mass migration of displaced works to urban centers in search of jobs. Urban life and industrial capitalism then made social theories necessary to explain this new configuration of social and economic life. Social theory, thus, was launched slowly at first in the interstices of the Enlightenment philosophies early in the long nineteenth century. Ultimately, a new social order made social theory necessary.

This being said, it remains to say just how this new kind of theory was grew out of Enlightenment philosophies that were, seemingly, anything but social. The answer can be found by a closer examination of the types of Enlightenment philosophies. William Bristow’s superbly clear article in The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (2017) describes three related yet different philosophical concerns of the Enlightenment: 1) The True, 2) The Good, 3) The Beautiful. Each, of course, had its own notable figures, even though most of them contributed to the other two concerns.

For the first concern, The True, notables include Descartes, Hume, and Newton—all philosophical founders of modern science. What they began came to be, late in the 1700s, a full-blown comprehensive theory of all three aspects of early Enlightenment philosophies. It was then that Kant set down the most radical theory of knowledge of the day in his sharp distinction between the external objects of knowledge and the subject’s phenomenological mental apparatus by which they are synthesized. For Kant, the reality of external objects can only be known in the subjective mind—not the experience of them, much less by abstract a priori reasoning. Just as important was Kant’s robust theory of moral behavior as obedient to a categorical imperative. Then, too, his idea of the sublime was also an important contribution to theories of The Beautiful. Though there were differences aplenty among Enlightenment philosophers, Kant was the one who systematically formulated a unique solution to theories of truth, morality, and beauty. It was Kant who provided a succinct (if not universally accepted) answer to the question What is Enlightenment? “Have courage to use your own understanding!” which is often rendered “Dare to know!”

In respect to Kant’s contributions to the evolution of social theory, it is important to note that the homebound Immanuel Kant published his most influential book, The Critique of Practical Reason, in 1788, the year before the French Revolution. (Kant interrupted his daily walks in his Königsberg only twice—when the French Revolution started and when reading Rousseau’s Emile.) The most memorable line in Kant’s The Critique of Practical Reason is a version of his basic moral principle: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.” This is not to say that Kant’s ideas caused the Revolution, but it does suggest that his very high-minded Enlightenment philosophy was subject to the ethos of the revolutions from 1775 to 1789. Otherwise put, Kant’s philosophy of knowledge was so closely tied to his moral politics as to make them philosophically inseparable.

Kant, therefore, illustrates just how the second of three Enlightenment philosophies, The Good, led most directly to modern social theory. The Good may seem to suggest ethics and morality, even religion, as the principal sources of the social theory and science. To a certain extent this is true. All of the great social theorists at the end of the nineteenth century—Marx, Weber, Durkheim, Freud—were, in different ways, preoccupied with social ethics, moral values, and religion. Marx and Freud meant to dismiss them, religion in particular. Weber and Durkheim lamented their decline, then attempted to imagine a future without them. Even these four social theorists owed a debt to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment—a debt that is seldom acknowledged. Although the social theories of Marx, Weber, Durkheim, and even Freud served to invent social sciences appropriate to their time, they had also to account for the passing of traditional society and the stunningly new urban worlds of their day. For them, the fate of modern moral order in the decline of religion was a question that could not have been asked, much less answered, late in the nineteenth century, were it not for the field ploughed by Locke, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and other proponents of Enlightenment in the eighteenth century.

Enlightenment ideas were clearly philosophical and not yet social theory. Still, they came into their own in a time of rapid social change. The seventeenth century was itself a turning point (if not a full-blown conjuncture) when Europe’s several traditional royal kingdoms were breaking apart into early versions of modern nation-states—this after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 ended the Thirty Years’ War. Also, in the mid-seventeenth century, the several colonizing powers of Europe required an enduring peace at home in order to attend to their colonizing enterprises abroad. The emerging nations in Europe agreed upon territorial borders and other interstate agreements meant to assure that peace. Their worldwide system of colonies and markets made early instances of state formation necessary, which, in striking instances, led to internal rebellions and revolutions. The English Revolution in 1688 was, of course, the first of these. It led to the establishment of democratic rule in England, including a Bill of Rights in 1689.

John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government was written in 1688 and is known to have influenced the democratizing elements in the English Civil War, as it influenced Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and the American Revolution after 1776, which in turn inspired the French Revolution of 1789. Locke’s line—that people are “willing to join in society with others… for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates”—clearly served as a model for Jefferson’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Montesquieu’s Spirit of Laws in 1748 was, many think, the first systematic social study with a sturdy social theoretical spine. Though the book’s subject is the political philosophy of laws, Montesquieu wrote in a decidedly sociological manner: “Considered as living in a society that must be maintained, [people] have laws concerning the relation between those who govern and those who are governed, and this is the political right.” Then too, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract in 1762 opens with the famous declamation: “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.” Rousseau’s treatise on the social contract as the primordial social aspect of modern democracies is surely among the most compelling and disciplined statements of the matter.

These are instances of political philosophies that, in effect, could not help but become embryonic social theories—a fact that becomes more evident in subsequent classical statements of the social nature of revolutions, of conflict and factions in independent states and, ultimately, of democracy in the modern state—thus: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, James Madison, Alexis de Tocqueville.

Burke is considered a founder of political conservativism. He was appalled by the French Revolution of 14 July 1789 because he believed it destroyed “the ancient principles and models of the old common law of Europe” that had been handed down from the past. Immediately after 14 July, Burke began to write notes for what became an undelivered letter to a young revolutionary-minded Frenchman. In final form it was published in 1790 as Reflections on the Revolution in France. Among the pamphlet’s many denunciations of the French revolutionaries is: “Not one drop of their blood have they shed in the cause of the country they have ruined.” Burke’s Reflections became the object of Anglo-American revolutionary Thomas Paine’s biting attack of Burke’s conservative attitude. His dismissal of Burke’s position in The Rights of Man, Being an Answer to Mr Burke’s Attack on the French Revolution (1791–92) is simply put: “[G]overnment is for the living, and not for the dead, it is the living only that has any right in it.” If Burke was a major conservative figure in Great Britain, Thomas Paine was the foundational figure of radial liberalism in America. Paine invented a theorical concept that, unfortunately, has not taken hold in today’s social thought. Imagine how social theory co...