eBook - ePub

The Bedrock of Christianity

The Unalterable Facts of Jesus' Death and Resurrection

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author writes that there lies a bedrock of truths about Jesus's life and ministry that are held by virtually all scholars of religion. Through an examination of each of these key facts, readers will encounter the unalterable truths upon which everyone can agree. Useful for both Christians and non-Christians alike, this study demonstrates what we can really know about the historical truth of Jesus' death and resurrection.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bedrock of Christianity by Justin Bass in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: Studying History Is Time Traveling

We are like paleontologists struggling to piece together a set of bones which a dinosaur had used all its life without even thinking about it. Simply seeing and assembling the data is a monstrous task.

N. T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God

Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure is a cult movie classic from the 1980s. Like great wine, this movie only grows better with age.45 The story is simple. Bill and Ted are failing their high school history class and need an A on their next presentation to graduate. Thankfully, a time-traveling phone booth (If you’re not old enough, Google “phone booth” to learn what that is) falls out of the sky, with comedian George Carlin inside. Bill and Ted are enabled to travel back in time through history to kidnap (and learn from) Socrates, Genghis Khan, Joan of Arc, Abraham Lincoln, Sigmund Freud, and Billy the Kid. I don’t want to spoil the ending for you, but they end up having a most excellent adventure.

If you could time travel to any time or place in history, where and when would you go? Is there an event you would most like to experience or a person you would most want to meet? What if you could travel to significant turning points in history such as the very moment when Socrates was walking to his trial before the citizens of Athens, when Lincoln was on his way to Ford’s Theatre, or when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon? Imagine being able to interview them concerning their aims, beliefs, hopes and dreams.

I hate to be the one to tell you this, but you will never be able to literally travel through time. It is a logical impossibility. For example, could one travel back in time before one’s own birth and kill one’s parents or grandparents? Think about that question too long and you will be permanently cross-eyed.

But here is the good news. We do have the tools to travel back in time thousands of years in the past and observe historical events such as the Jewish war with Rome in AD 66–70. We can meet historical figures such as Socrates, Abraham Lincoln, and Julius Caesar, or even John the Baptist, Jesus, and Paul. We can discuss justice or courage with Socrates as we walk with him down the streets of Athens. We can behold the magnificent beauty of the temple in Jerusalem with Josephus or behold the horror of Jesus’ crucifixion outside the city walls. We don’t have time-traveling phone booths—we don’t even have phone booths anymore—but we do have the tried and tested tools of the historical method.46 These tools enable us to time travel through history.

WHAT HISTORIANS WANT

In one sense, “history” is everything that happened in the past, every second of every day since the beginning of the universe. However, I mean something more specific when I talk about studying history or the historical method. In this second and more useful sense, history is the “knowable past,” the people and events of history for which reliable sources have survived.

In some cases, such as with Alexander the Great or many of the Roman Caesars and Egyptian Pharaohs, we have physical evidence of their existence such as coins, art, busts, statues, and even their mummies! However, most figures from history we only know through surviving written sources. Sometimes these are written by eyewitnesses to the events or person(s) they are describing, but in most cases, they are written by individuals many generations later. Like a paleontologist trying to piece together his newly discovered group of bones, historians work with what the sands of time have delivered them to piece together a particular historical event or understand the life, aims, beliefs, and death of a historical figure. How well they can do that really depends on the nature of the surviving sources.

We engaged in this art of time travel in the prologue when we sought to learn as much as we could from the epic meeting between Peter and Paul in Jerusalem. The one written source from Galatians 1:18 could only take us so far. Yet, since Galatians was written by a reliable eyewitness, Paul, we were able to explore in detail this event that occurred in Jerusalem sometime between AD 33 and 38.

In Bart Ehrman’s many books on early Christianity, he discusses what makes for a reliable source: “What historians want, in short, are lots of witnesses, close to the time of the events, who are not biased toward their subject matter and who corroborate one another’s points without showing signs of collaboration.”47

This can be laid out as four distinct items that constitute a historian’s wish list:

(1)Early dating: sources that are very close to the time of the person or event

(2)Eyewitnesses: multiple people who saw and/or recorded the event

(3)Corroboration: eyewitnesses and sources that corroborate with one another without collusion

(4)Unbiased: sources that are not biased toward their subject matter

As Ehrman concludes, “Would that we had such sources for all significant historical events!”

Now, if we followed this criterion woodenly, we would have to throw out most of ancient history we now take for granted. In almost all cases, we don’t have a person writing about an event who is unbiased or disinterested, and most of our sources date many generations, even hundreds of years, after the person or event that is being described.

For example, Oxford historian A. N. Sherwin-White says that historians of ancient history are usually

dealing with derivative sources of marked bias and prejudice composed at least one or two generations after the events they describe, but much more often, as with the Lives of Plutarch or the central decades of Livy, from two to five centuries later. Though connecting links are provided backwards in time by series of lost intermediate sources, we are seldom in the happy position of dealing at only one remove with a contemporary source.48

Sherwin-White goes on to say that even with many generations separating an event from the person writing about it, this does not prevent the historian from being able to say quite a lot concerning “what really happened.”49 To have the kind of sources and eyewitnesses Ehrman is describing is almost unprecedented, at least from the ancient world.

To be fair to Ehrman, that is why he calls it a wish list!

I will argue in chapter 3 that, incredibly, the creedal tradition found in 1 Corinthians 15:3–7 does pass this high threshold for sources.

But for now, I want to emphasize that most of the history we take for granted does not come even close to meeting the wish-list criteria for reliable sources. Yet that does not present a problem to ancient historians (or for us) who desire to time travel to experience this event or meet that historical figure. As Sherwin-White pointed out above, even with multiple generations separating an event from the author describing it, we are still able to learn a lot concerning what really happened.

To illustrate this further, let’s look briefly at four examples from history: an emperor, an ancient war, a philosopher, and a Baptist.

THE KNOWABLE PAST

Tiberius Caesar is one of the Roman emperors for whom we have multiple somewhat reliable biographical accounts. He ruled the Roman Empire from AD 14–37 and was the most powerful man in the world at that time. We have archaeological evidence of his reign in the coins he issued, but to learn about the man himself, we must rely on biographical material. Only a handful of written sources about him have survived, some of which were written long after his death. Sherwin-White discusses the evidence for Tiberius:

The story of [Tiberius’] reign is known from four sources, the Annals of Tacitus and the biography of Suetonius, written some eighty or ninety years later, the brief contemporary record of Velleius Paterculus, and the third-century history of Cassius Dio. These disagree amongst themselves in the wildest possible fashion, both in major matters of political action or motive and in specific details of minor events.… But this does not prevent the belief that the material of Tacitus can be used to write a history of Tiberius.50

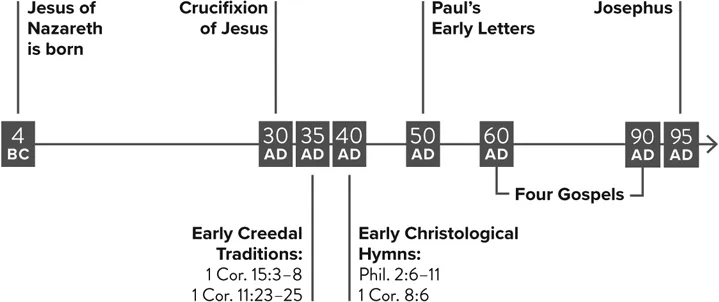

Despite the lateness and disagreement among the biographies of Tiberius, this Caesar is still part of the knowable past. We can time travel to meet him through Tacitus and Suetonius, even though they were eighty to ninety years later. To put that time frame in perspective, the latest biography of Jesus in the New Testament is the Gospel of John, which dates to around sixty years after Jesus’ death. Mark is the earliest, dating to somewhere between thirty and forty years after Jesus’ death. Even better, we have Paul’s early letters, which were written within twenty to twenty-five years after Jesus’ death. But with the traditions and hymns about Jesus quoted in Paul’s early letters, we can reach back even further. In particular, 1 Corinthians 15:3–7, as we will see, is dated by 99 percent of scholars to within a decade after Jesus’ death.

Tiberius was the most powerful man in the world of his day. Jesus was one of the poorest, belonging to the peasant class as a Jewish carpenter. He even died the most shameful death, a slave’s death, on a cross during Tiberius’ reign. Yet we have far more reliable written sources and closer to the time of Jesus’ actual life and death than this Caesar of Rome.

The second example is the events of the Jewish war with Rome, which began in AD 66 and ended in 70 when the Roman general Titus broke down the walls of Jerusalem and burned the temple to the ground. As a result of this event, we have archaeological evidence of the war to this very day. Yet how many contemporary eyewitness sources do we have for the most significant war in the first century? Only one. Jewish historian Josephus wrote down his eyewitness account in a book called The Jewish War only a few years after the event, around AD 75: “As for the History of the War, I wrote it as having been an actor myself in many of its transactions, an eyewitness in the greatest part of the rest, and as not unacquainted with anything whatsoever that was either said or done in it” (Ag. Ap. 1.55).

Using the tools of the historical method, historians do their best to distinguish clear exaggeration and the mix of legend and history from the places where Josephus is telling us “what really happened.” All in all, Josephus gives us many bedrock facts about the Jewish war with Rome despite being on Emperor Vespasian’s payroll, greatly exaggerating numbers,51 and occasionally adding legendary events to the story. But through the historical method we can time travel and witness the massacre at Masada (J.W. 4.398–404; 7.252–406), observe that Titus’ soldiers in jest played with different postures for crucified victims until they ran out of crosses (J.W. 5.449–551), and learn of many of the other horrors of the Jewish war with Rome.

For a third example, if we want to walk the streets of Athens with Socrates, listening to his philosophical wisdom, how do we do it? Like Jesus, Socrates didn’t write anything. The only way we can meet the “historical Socrates” is through the undeniably biased writings about him from Plato’s Dialogues, Xenophon’s Memorabilia and Symposium, and Aristophanes’ Clouds. These were all contemporary disciples of Socrates and wrote within decades after his death. We learn from all of them that the “historical Socrates” occupied himself primarily with ethics, seeking to help everyone around him toward excellence of character. He was the first to raise the problem of definitions and used a unique method of argument and debate known as the dialectic method.

According to Plato, Socrates was told by the oracle at Delphi that he was the wisest man on earth. Socrates was perplexed by this pronouncement. He thought of himself as someone who really knew nothing. Then he finally figured it out. He was the wisest because he was the only one who knew he was not wise, the only one who knew he did not know: “I am wiser than this man; for neither of us really knows anything fine and good, but this man thinks he knows something when he does not, whereas I, as I do not know anything, do not think I do either. I seem, then, in just this little thing to be wiser than this man at any rate, that what I do not know I do not think I know either” (Plato, Apology 21D–E).

Eventually, the leaders of Athens accused him of leading the youth astray, teaching “strange gods” (Xenophon, Memorabilia 1.1), and even “wizardry” (Plato, Meno 80B). The Athenian Senate condemned him to death by drinking hemlock. His last words, according to Plato (“Crito, we owe a cock to Aesculapius. Pay it and do not neglect it”) are recorded in his famous dialogue Apology, which means “defense.” He was seventy years old when he died in 399 BC (Plato, Apology 70D).

Scholars debate to this day whether Plato, Xenophon, and Aristophanes give us the historical Socrates or an idealized version of Socrates whom they used to teach their own philosophical theories and concepts. The majority view is that the historical Socrates is best represented in Plato’s earliest dialogues (Apology,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Prologue: When Titans Meet

- Chapter 1: Studying History Is Time Traveling

- Chapter 2: Bedrock Eyewitness: The Apostle Paul

- Chapter 3: Bedrock Source: 1 Corinthians 15:3–7

- Chapter 4: Crucifixion: “Christ Died for Our Sins and He Was Buried”

- Chapter 5: Resurrection: “He Was Raised on the Third Day”

- Chapter 6: Appearances: To Peter, the Twelve, More than Five Hundred, James, and Paul

- Chapter 7: The Rise of the Nazarenes: “Fighting against God”

- Conclusion: “This Is Wondrous Strange”

- Epilogue: New Creation

- Bibliography

- Scripture Index

- Ancient Sources Index