![]()

1

Introduction: In Search of Lost Times

The ages live in history through their anachronisms.

Wilde, “Phrases and Philosophies.”1

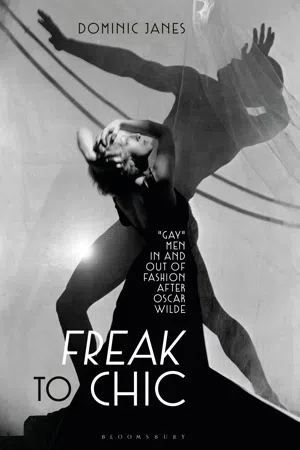

In the interwar period, queer styles came into fashion. What had been freakish became chic. This book explains how this came about and why it did not last. Accompanied by bunches of flowers and attending to glamorous women, a select number of homosexual and bisexual men were allowed to dine at many of the top social tables on both sides of the Atlantic in an age when their sexual choices were widely criminalized. On the way, they contributed immensely to the artistic achievements of their times. The design of George Kukor’s film My Fair Lady (1964), which was based on George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion (1913), emerged from these milieus. Its story of the transformation of a cockney flower-seller into a glamorous socialite bore some comparison to the rise from middle-class obscurity of Cecil Beaton, who designed many of the film’s costumes. As a confirmed bachelor and aesthete, he insisted that his working environment be as beautiful as possible. He pestered the studio for ever more plants and bouquets with which to furnish his Hollywood apartment since “in England, this was the time of the year when I could hardly drag myself from my garden for fear of missing the opening of a bud.”2 For queer men such as Beaton, fine decor, exotic blossoms, and the women who adored them provided a lusciously decorative mask that, by the 1960s, barely concealed their sexual deviance.

Suitors have long been encouraged by florists to “say it with flowers,” but in fact blossoms could be employed in poetry and art to hint at a wide variety of thoughts and feelings. They have been analyzed as providing “an alternative model of the production (of meaning) which would take into account what has been rejected and repressed in logocentric systems of thought and knowledge, namely plurality, the feminine, the unconscious and the signifier.”3 Not all flowers were bright and gay: some were dark, strange, and evocative of decadence. Men who dared to explore same-sex desire more openly were drawn by the dramatic power of the contrast between lushly beautiful surfaces and the fleshly truths that they concealed. Beaton hinted at troubling aspects of life through an exploration in much of his work as a celebrity photographer of strange juxtapositions and queer contrasts between beauty and ugliness, the extraordinary and the everyday. His was a carnivalesque imagination that celebrated, like that of his sexual fellow-traveler Jean Cocteau in France, “stars (‘the sacred monsters’), the boxers, the clowns, [and] the fashion mannequins [i.e., models].”4 Other writers and artists who were not dependent, as Beaton was, on the patronage of high society were able to explore contrasts between beauty and beastliness with even greater openness. In France, Jean Genet produced overtly queer books such as Our Lady of the Flowers (1943) and Miracle of the Rose (1946).5 In the United States, Tennessee Williams was to write of the intense passions that would tear open the aesthetic camouflage in Suddenly Last Summer (1958). The garden of Sebastian the queer aesthete, he wrote, “may be as unrealistic as the décor of a dramatic ballet,” featuring “massive tree-flowers that suggest organs of a body, torn out, still glistening with undried blood.”6 At the end of the play, all that is left of Sebastian after a horrific, cannibalistic assault is described as looking like a “big white-paper-wrapped bunch of red roses [that] had been torn, thrown, crushed!”7

Many people thought that homosexual sex was wrong and that the men who liked it were little better than beasts. Some queer men openly embraced their seemingly ugly deviance in the countercultural mode of Genet, while others denied its existence. But there was another option: to conceal in plain sight. This, essentially, was Oscar Wilde’s choice. As the dandy Lord Goring says to the morally compromised politician Sir Robert Chiltern in Wilde’s An Ideal Husband (1895): “in England a man who can’t talk morality twice a week to a large, popular, immoral audience is quite over as a serious politician. There would be nothing left for him as a profession except Botany or the Church.”8 Wilde insinuates that the truly monstrous hypocrite can only survive when he takes spiritual or worldly beauty as his occupation. Oscar Wilde had been one of the most glamorous celebrities of his age. The images that we have of him today have been powerfully influenced not just by his literary works but also by the way in which he performed himself.9 In his early life, he was both feted and mocked as a willowy aesthete. During his lecture tour to the United States in 1882, he became notorious for his interest in unusual fashions and for his allegedly effeminate fascination with aesthetic style in general and with flowers in particular.10 A decade later, The Star reported that he had appeared at a theater premiere in the company of a “suite of young gentlemen, all wearing the vivid dyed carnation which has superseded the lily and the sunflower.”11 By that time, his body had expanded from svelte to corpulent, and he was being lampooned as a gourmand. Rumors concerning his sexual interests had been spreading in London for many years before his trials made him the most notorious sodomite of the age.

This book does not explore the reception of Oscar Wilde’s literary works. It does, however, examine the ways in which images associated with his life and style became constitutive of constructions and perceptions of male homosexuality. It likewise follows the queer pattern of Wilde’s own life by focusing on fashionable society in London seen in connection with metropolitan milieus across the Atlantic and in Paris. The book aligns with the trend identified by the American historian of gender and sexuality Regina Kunzel that “queer histories are increasingly [seen as] transnational, tracing the global circuits of sexual ideas, practices, politics and subjects.”12 Forms of queer transatlantic modernism developed as Anglophile Americans influenced cultural life in London and men from the UK had made increasingly frequent visits to New York. Wilde’s lecture tour of the United States in the early 1880s was a precursor of this process. This book, therefore, is a case study focused on a particular city, but one that invites related engagements with queer fashion in other locations around the globe.13 John Potvin, in his study of queer bachelordom, has talked of the “omnipresence of Wilde” in early-twentieth-century Western culture.14 Even though Wilde was widely reviled, he became a figure against which evolving standards of normative masculinity were measured. He thereby became associated with a heady combination of ugliness and aestheticism, disgrace and fashionability, freakiness and chic.

That last term—chic—has been established in English since at least the mid-nineteenth century. It refers to skill, style, and taste and was acquired from French, where it was originally regarded as slang, and may have in turn been derived from the German word schick. Fin-de-siècle modes of dandyism had a powerful influence on the formation of queer styles of male self-expression during this period. While the sexually assertive woman—the vamp—flickered alluringly across the screens of movie theaters, the styles of Wilde were revamped for new groups of seemingly androgynous men who proclaimed themselves to be “gay” in the sense of happy. This book tells the story of how queerness in the sense of gender ambiguity came—albeit briefly and precariously—into fashion in the 1920s. However, this style and those who generated it swiftly fell out of vogue in the 1930s as the sexual content of that queerness became the subject of popular derision. These were decades that saw a dizzying pace of cultural change that involved, for some people at least, greater opportunities for sexualized self-expression. Freak to Chic explores the birth of the queer culture that would in time lead to lesbian and gay liberation and new forms of sexual identity. It centers on the question of how freakery and fashion came briefly into alignment in the form of “freak chic.”

The word “freak” was sometimes used in quite explicit ways to refer to same-sex desire, including by people of color, as in Harlem Hamfat’s song “Garbage Man—or The Call of the Freaks,” or “Freakish Man Blues” by George Hannah.15 But the word was also used in a much wider sense to refer to countercultural behavior, especially by wayward and often fashion-conscious youth. In this sense, the interwar period prefigured a similar process of appropriation of freaks and freaking by the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s.16 In 1978, the American rhythm-and-blues band Chic released a hit disco song “Le Freak” on their new album C’est Chic. It was inspired by their experience of failing to meet with Grace Jones on New Year’s Eve after being turned away by bouncers at the hot new nightclub Studio 54, which had just opened in New York. The record was a huge commercial success, becoming the best-selling album for their label, Warner Music, prior to Madonna’s “Vogue” (1990). In 1995, John Galliano titled a fashion show in Paris “Le Freak C’est Chic,” in which “giants, identical twins, fat women, bodybuilders, old men and dwarves” were sent down the catwalk.17 Such individuals are no longer exhibited to the paying public in freak shows, but they can be paraded for their shock value in the promotion of luxury commodities.

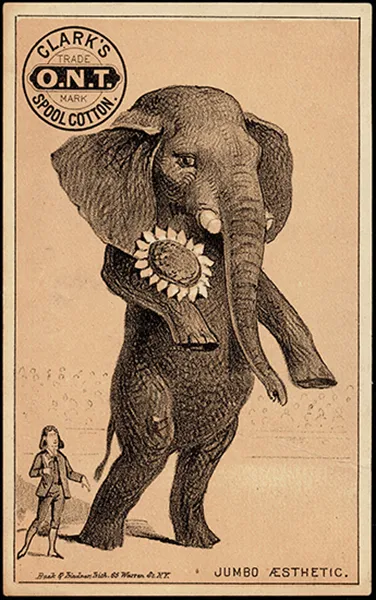

Wilde’s visit to the United States marked a key moment when the world of the freak show collided with the world of aesthetic culture and fashion. It was even rumored—falsely—that the great impresario of circuses and freak shows Phineas Taylor (“P. T.”) Barnum had offered Wilde £200 if he would ride the famous elephant Jumbo down Broadway in New York with a lily and a sunflower grasped in either hand (Figure 1.1).18 Cartoons of the time regularly depicted Wilde as a bizarrely dressed, flower-obsessed impersonator of the mores of European aristocracy. The world of popular entertainment included strong traditions of blackface minstrelsy that influenced the ways in which the performances of Wilde and his aesthetes were mocked, particularly in the United States.19 Many of these American representations were explicitly racialized, depicting people of African or Asian ethnicity as ridiculous for supposedly aping the pretentions of the visiting Irishman.20

Figure 1.1 Clark’s O.N.T. Spool Cotton, Jumbo Aesthetic (New York: Buek and Lindner, c.1882). Reproduced courtesy of Boston Public Library Arts Department.

There had, however, been a tradition of parodying Black dandies in London since the eighteenth century. One print published in 1772 depicted Julius Soubise. He had become famous as the former slave and close companion of the Duchess of Queensberry, who had named him after a courtier of Louis XV of France.21 Even though those who shaped Western fashion have often been White, the ways in which they were critiqued could still draw on racial prejudice. Celts, for instance, were not always thought of as being quite the same shade of pale as Anglo-Saxons. If queerness is understood as having been constructed through contestation between opponents and proponents, then it will contain within it elements with which we may be uncomfortable, including some that are racist, misogynist, or self-shaming. Elspeth Brown, in her Work! A Queer History of Modeling (2019), raised the concern that queer approaches might sometimes lead to neglect of other important markers of identity. This book, unlike hers, does not explore case studies of people of color. Nevertheless, the study of relatively privileged white men such as Wilde and Beaton need not mean that classed and gendered intersectionality is eclipsed in the pursuit of insights into sexuality.22 Elite lives can tell us a great deal about the systems of classification and control in which they were enmeshed.

The word “queer” usually meant strange or freakish in the first half of the twentieth century. However, it was sometimes applied in ways that betray some suspicion of sexual peculiarity. An early example of this was the reference to Lord Rosebery as a “snob queer” by Wilde’s nemesis, the Marquess of Queensberry.23 He feared that his eldest son, Francis, Viscount Drumlanrig, had been seduced by Rosebery, and he was equally concerned about relations between his younger son Alfred “Bosie” Douglas and Oscar Wilde.24 But his phrase also implied that the man who was prime minister from 1894 to 1895 was, like Wilde, a social climber with an unorthodox marriage (his wife was Jewish). The past indeterminacy of queerness is argued by many contemporary writers of queer history to be one of its enduring strengths. Queerness can be seen as involv...