- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The War of 1812, A Short History

About this book

This abridged edition of Donald R. Hickey's comprehensive and authoritative The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict has been thoroughly revised for the 200th anniversary of the historic conflict. A myth-shattering study that will inform and entertain students and general readers alike, The War of 1812: A Short History explores the military, diplomatic, and domestic history of our second war with Great Britain, bringing the study up to date with recent scholarship on all aspects of the war, from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada.

With new information on military operations, logistics, and the use and capabilities of weaponry, The War of 1812: A Short History explains how the war promoted American nationalism, reinforced the notion of manifest destiny, stimulated peacetime defense spending, and enhanced America's reputation abroad. Hickey also concludes that the war sparked bloody conflicts between pro-war Republican and anti-war Federalist neighbors, dealt a crippling blow to the independence and treaty rights of American Indians, and solidified the United States' antipathy toward the British. Ideal for students and history buffs, this special edition includes selected illustrations, maps, a chronology of major events during the war, and a list of suggested further reading.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The War of 1812, A Short History by Donald R. Hickey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Coming of the War, 1801–1812

On March 4, 1801, Thomas Jefferson walked from his boardinghouse in Washington City, as the nation’s new capital was then called, to the Capitol Building, where he was inaugurated as third president of the United States. The ceremony was short and Spartan. The nation’s new leaders favored a simpler and more democratic style than their Federalist predecessors. They also planned to adopt a new set of policies. It was these policies—initiated by Jefferson and carried on by his friend and successor, James Madison—that put the United States on a collision course with Great Britain and ultimately led to the War of 1812.

Republicans did not differ with Federalists over the broad objectives of American policy in this era. The French Revolution, which had erupted in 1789, plunged Europe into warfare. Known as the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, this conflict lasted from 1792 to 1815. Essentially a world war, the struggle cast a long shadow across the Atlantic as the two leading belligerents, Great Britain and France, repeatedly encroached on American rights in the pursuit of victory. During this era of sustained warfare, all Americans agreed that the new nation should promote prosperity at home while protecting its rights and preserving its neutrality abroad. But what was the best way to achieve these ends? It was this question, more than any other, that divided Americans into two political camps.

The Federalist Ascendancy (1789–1801)

The Federalists, who controlled the national government in the 1790s, subscribed to the old Roman doctrine that the best way to avoid war was to prepare for it. Under the leadership of President George Washington and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, they implemented a broad program of financial and military preparedness. Besides adopting Hamilton’s financial program (which included trade and excise taxes, a funded national debt, and a national bank), they expanded the army, built a navy, and launched a rudimentary system of coastal fortifications. Their aim was not simply to deter war but to put the nation in a position to fight and finance a war if hostilities ever erupted.

Besides embracing preparedness at home, the Federalists pursued a pro-British foreign policy abroad. The cornerstone of this policy was the Jay Treaty, an Anglo-American agreement negotiated in 1794 that regulated commerce between the two nations and defined Britain’s belligerent rights and America’s neutral rights in the European war. The Republicans, who never got over their fear and hatred of Britain from the American Revolution, denounced the Jay Treaty as a one-sided sellout of American interests. In a typical Republican editorial, one newspaper called it the “death-warrant to our neutral rights.” Whatever its liabilities, there is no denying that the Jay Treaty served American interests in two important ways. It ensured peace with the Mistress of the Seas, the one nation that could seriously threaten the young Republic’s growing trade. It also ushered in an era of friendship with Britain that allowed American trade, and hence the entire American economy, to flourish. American exports, which stood at $33 million in 1794, nearly tripled to $94 million in 1801.

The only liability of the Jay Agreement was that it infuriated France, which was still nominally bound to the United States by a treaty of alliance the two nations had signed in 1778 during the American Revolution. Determined to bully the United States into repudiating the Jay Treaty, France severed diplomatic ties and unleashed its warships and privateers on American trade. This led to the Quasi-War, an undeclared naval war with France that lasted from 1798 to 1801. The new Federalist navy acquitted itself well in this war. Cruising mainly in the Caribbean, where most of the French depredations had occurred, the navy defeated or destroyed three French warships (while losing only one of its own), captured eighty-two French privateers, and recovered seventy American merchant vessels that were in French hands. In response to U.S. determination, France called off its war on American trade and agreed to restore normal relations.

Although their policies in the 1790s had served the nation reasonably well, the Federalists were voted out of office in 1800. Their approach to politics was too elitist for the rising spirit of democracy in this era and their pro-British foreign policy ran counter to the widespread distrust and hatred of Britain that was a legacy of the American Revolution. In addition, some of their policies during the Quasi-War—a boost in taxation and the adoption of the repressive alien and sedition laws—were unpopular with many Americans. As a result, the Republicans won control of the presidency and both houses of Congress.

The Republicans Take Control (1801)

When the Republicans took office in 1801, they reversed many of the policies that they had inherited from the Federalists. Convinced that the excise taxes discriminated against their constituents in the South and West, they repealed these duties in 1802, and regarding the national bank as an aristocratic monopoly subject to foreign control, they refused to renew its charter when it expired in 1811. Preferring to rely on militia and privateers as well as small and inexpensive gunboats, the Republicans trimmed the army and took most of the navy’s warships out of service. They also used the army’s officer corps as a dumping ground for the party faithful.

Although these policies weakened the nation financially and militarily, they were popular with the American people and initially at least did no harm. Great Britain and France concluded the preliminary Peace of Amiens in 1801 and remained at peace until 1803. When the European war resumed, both belligerents once again interfered with American trade and encroached on American rights. Because the British controlled the high seas, most Americans found their behavior more offensive. Soon a whole range of issues emerged to drive the two English-speaking nations apart.

James Madison (1751–1836) was president during the War of 1812. He was not a strong leader and was unable to impose his will on Congress or to inspire the country. (J. A. Spencer, History of the United States)

Impressment and the Orders-in-Council

To fill out the crews of its chronically undermanned warships, the Royal Navy routinely stopped American merchant ships on the high seas and impressed or drafted seamen into service. Although the press gangs were supposed to target only British seamen, through accident or design a fair number of American citizens got caught in the dragnet. Between 1803 and 1812, an estimated 6,000 American tars (as seamen were then called) were forced to serve on British warships.

British officials were willing to release any Americans whose citizenship could be proven, but this could only be done through diplomatic channels, a process that could take years. In the meantime, American victims of impressment were subjected to all the misery of British naval service (where discipline was enforced with the cat-o’-nine tails) and to all the horrors of a war that was not their own. Moreover, any impressed tar who accepted the enlistment bounty while in service was considered a volunteer regardless of any evidence of citizenship that might be produced.

Besides impressing seamen from American ships, the British periodically interfered with America’s lucrative trade with the West Indies and often violated American territorial waters, conducting searches and making seizures within the three-mile limit. In addition, they made sweeping use of naval blockades to close off the trade of their enemies, and they insisted on a much broader definition of contraband than the United States was willing to concede.

The British offered to resolve some of these problems in the Monroe–Pinkney Treaty of 1806. This agreement was designed as a successor to the Jay Treaty (most of whose clauses had expired in 1803), although in the realm of commerce and neutral rights it was actually more favorable to the United States. But President Jefferson found it so unsatisfactory (mainly because it did not address the issue of impressment) that he refused to submit it to the Senate for approval. The loss of this treaty was a great turning point in the period. By rejecting the agreement, the United States missed a chance to re-forge the Anglo-American accord of the 1790s and to take a road that might have led to peace and prosperity instead of one that led to trade restrictions and war.

After the loss of the Monroe–Pinkney Treaty, Anglo-American relations steadily deteriorated. In the summer of 1807 there was a full-blown war scare when the British frigate Leonard (52 guns) fired on the U.S. frigate Chesapeake (40 guns), killing and wounding a number of the crew. After the Chesapeake surrendered, the British removed four seamen that were deserters from the Royal Navy. The British government did not claim the right to search or impress from neutral warships (which were considered an extension of a nation’s territory), and it disavowed the attack and offered to pay compensation. But the issue became entangled with others, and a settlement was delayed until 1811. In the meantime, the Chesapeake affair festered, contributing to the rising tide of anti-British feeling in the United States and the drift toward war.

Shortly after the Chesapeake outrage, another problem surfaced that was to bedevil Anglo-American relations even more. This was the Orders-in-Council, a series of executive decrees issued by the British government between 1807 and 1809 that sharply curtailed American trade with the European Continent. The British conceded that the Orders did not accord with international law but justified them as a necessary response to Napoleon’s Continental Decrees, which prohibited all trade with the British Isles. This did little to pacify Americans, who believed, with some justice, that both belligerents were using their anti-commercial war as a pretext to loot American trade. American losses were considerable. Between 1807 and 1812, Great Britain and France and their allies seized some 900 American ships.

The Restrictive System (1806–1811)

To combat the growing assault on American commerce, Republicans adopted their own restrictions on trade. Known collectively as the restrictive system, these measures grew out of the Republican belief that American trade could be used as an instrument of foreign policy. The underlying assumption was that Great Britain (and to a lesser degree France) and their West Indian colonies needed the United States as a source for food and other raw materials and as a market for their finished projects. By limiting or cutting off American trade, the Republicans believed they could force the European belligerents to show greater respect for the young Republic’s neutral rights.

In 1806 Congress enacted a partial non-importation act that prohibited a select list of British imports. In 1807 Congress added a general embargo that prohibited all American exports. In 1809 these measures were repealed in favor of a non-intercourse act that permitted trade with the rest of the world but barred all trade with Britain, France, and their colonies. This law was repealed in 1810, but in 1811 Congress passed a fresh non-importation law that prohibited all imports from Britain.

These measures failed to win any concessions from the belligerents but instead boomeranged on the United States, destroying American prosperity and depriving the federal government of much-needed revenue that normally came from taxes on trade. American exports fell from a peak of $108 million in 1807 to a low of $22 million in 1808, and American imports declined from a high of $139 million in 1807 to a low of $53 million in 1811. In a similar vein, government revenue, which peaked at $17 million in 1808, fell to less than $8 million in 1809. The ineffectiveness of the restrictive system exposed Republicans to sharp criticism from the Federalists, who had opposed Republican foreign policy ever since the loss of the Monroe–Pinkney Treaty.

Growing Tension (1811)

Two other developments contributed to the deterioration of Anglo-American relations in 1811. The first was the Little Belt incident, a kind of Chesapeake affair in reverse, in which the U.S. frigate President (54 guns) exchanged fire at night with the much smaller British sloop Little Belt (20 guns), killing and wounding a number of the crew. Since it was never clear who fired first, the British chose not to make an issue of the matter, although many Americans considered it just retaliation for the Chesapeake affair.

The other development was the outbreak of an Indian war in the Old Northwest. This conflict was an outgrowth of a series of dubious land cession treaties that William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, had imposed on the Indians, culminating in the Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809. This treaty was the last straw for two Shawnee brothers, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (better known as the Prophet), who headed an Indian confederation opposed to the further loss of Indian lands and the destruction of the traditional native way of life.

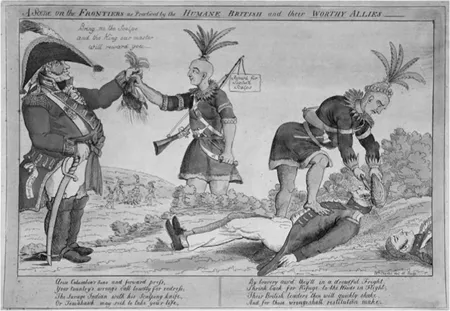

Harrison’s policies led to a growing number of Indian raids on the frontier. Because the Indians got the bulk of their supplies (including their muskets) from the British in Canada, most Americans were convinced that the British were behind the raids. “We have had but one opinion as [to] the cause of the depredations of the Indians,” said Niles’ Register. “They are instigated and supported by the British in Canada.”

This contemporary cartoon suggests that the British were behind Indian raids on the American frontier before the War of 1812. In truth, the British sought to restrain their native allies but were not always successful. (Watercolor etching by William Charles. Library of Congress)

In the fall of 1811 Harrison marched into Indian territory to break up the native settlement at Prophetstown, which was on the Wabash River just below the mouth of the Tippecanoe River. The result was the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7. Although Harrison suffered heavy casualties, he drove off the Indians and then burned their village and food supplies. This marked the beginning of an Indian war that later blended into the War of 1812. The outbreak of the Indian war rendered the entire frontier unsafe. “Most of the citizens in this country,” Harrison reported in 1812, “have abandoned their farms and taken refuge in such temporary forts as they have been able to construct.”

The War Congress Meets

By the time the Twelfth Congress—known to history as the War Congress—met on November 4, 1811, there was growing talk of the war. The British had made no concessions on the issues in dispute, and any settlement of the leading issues—the Orders-in-Council and impressment—seemed remote. Many Republicans were frustrated with the restrictive system, which seemed to do more harm to the United States than to Britain or France. To a growing number of Republicans, war seemed to be the only answer.

The Republicans had solid majorities in both houses of Congress, controlling 75 percent of the seats in the House and 82 percent in the Senate. But for years the party had lacked competent floor leadership and been torn apart by factionalism. The regular Republicans, who usually followed the administration’s lead, could usually muster a majority, but on occasion dissident members of the party combined with Federalists to block legislation. “Factions in our party,” complained one Republican, “have hitherto been the bane of the Democratic administration.”

Fortunately for the administration, there was a new faction in the War Congress capable of providing the leadership and firmness that hitherto had been lacking. These were the War Hawks, a group of about a dozen ardent patriots who came mainly from the South and West. Too young to remember the horrors of the last British war, the War Hawks were willing to hazard another contest to vindicate the nation’s rights.

Heading the War Hawks was young Henry Clay of Kentucky. Although not yet thirty-five and never before a member of the House, Clay was elected speaker and lost no time in establishing his authority. Heretofore, the speakership had been largely ceremonial, but Clay molded the office into a position of power, and, as one contemporary put it, he “reduced the chaos to order.” By directing debate and interpreting the rules, by packing key committees with War Hawks and by acting forcefully behind the scenes, Clay kept the war movement on track.

War Preparations (1811–1812)

The president submitted his opening address to Congress on November 5, 1811. Focusing on the Orders-in-Council, Madison accused Great Britain of making “war on our lawful commerce” and urged Congress to put the nation “into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis.” Congress responded by adopting a comprehensive program of war preparations. The army was expanded, the recruitment of short-term volunteers was authorized, and the militia was readied for service. The nation’s warships were put into service, and money was appropriated to purchase munitions and other war material and to build and repair coastal fortifications. A war loan was also authorized, although Republicans refused to consider new taxes until war was actually declared.

Most of the war prepa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to Bicentennial Edition

- Preface to First Edition

- Introduction

- 1. The Coming of the War, 1801–1812

- 2. The Campaign of 1812

- 3. The Campaign of 1813

- 4. The British Counteroffensive, 1814–1815

- 5. The Inner War

- 6. The Peace of Christmas Eve

- Legacies

- Chronology

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Index

- About the Author