Chapter One Im Kwon-taek: Korean National Cinema and Buddhism

In 1926 Han Yong-un, an eminent Buddhist master and leader in the movement to free Korea from Japanese occupation, published a collection of poems, Silence of Love (Nim ŭi ch’immuk) in which he assumed the persona of a woman abandoned by her lover. In the title poem, she looks out across the mountains and the path through them by which he left her; but, with the dialectical logic of Buddhism, she finds in her loss the implication of its opposite, and so concludes by affirming her anticipation of re-union with him. Silence of Love is usually read allegorically simultaneously in religious and political terms, with the absent lover figuring both the void at the heart of Buddhist ontology and the Korean national homeland abducted by the Japanese invaders.

Twenty years later, a similar scene occurs in Yun Yong-gyu’s film Home is Where the Heart Is (Maum ŭi kohyang, 1948), one of the few Korean films from before the civil war that survives to us. In this film the erotic metaphor is oedipalized. To-song, a young boy being raised by the monks at Chongnam temple, desperately awaits the return of his mother who abandoned him and who now lives in Seoul. He asks an old woodcutter if his mother is beautiful, and when he hears that she is, he raises his eyes to the mountains that surround him, to the peaks and the forests, which we see from his point-of-view. As these figure both his mother’s beauty and her absence, To-song’s scopophilic gaze, like Han’s lyric voice, makes palpable and present that which is missing – a function that has been proposed as fundamental to the cinematic signifier and its Oedipal operation, and one that the film’s narrative will confirm by bringing him a surrogate mother who is nevertheless invested with all the erotic intensity of a lover.

Thirty years later, the same motifs of loss and restoration begin to pass obsessively through the films of Im Kwon-taek. In his mature work, Im explored precolonial cultural forms in order to engage the question of Korean national identity, especially as it has been alienated and thrown into crisis by the multiple forms of colonization to which the country has been subject. Of the traditional cultural vocabularies Im interrogated, Buddhism will be the one considered in detail below. Like Han and Yun, he mobilized the resonant metaphors of eroticism and landscape that Buddhism contains, though the quite different historical conditions of the three artists ensured that those metaphors would be differently inflected. But before turning to Im’s use of Buddhism, we must consider his confrontation with what, for a filmmaker, is an especially immediate form of alienation, that is, a national cinema subject to neocolonial political control and censorship and marginalized by the global hegemony of the U.S. capitalist culture industries. We begin, then, with Im’s attempt to turn the colonized Korean film industry into the vehicle of a national culture.

I. Korean National Cinema: Im Kwon-taek as Auteur

Although the theoretical status of the concepts of the art film, national cinema, and the director-as-author has been largely undermined, practically they continue to organize scholarship. Even so, to approach a Korean auteur and a Korean art cinema committed to national reconstruction in the general terms they demarcate demands at the outset some justification in an account of the material conditions of film production in South Korea. Designating a number of locally-specific variants either within or on the edges of studio production, the concept of the art film mediates between the division of labor of the industrial feature film and the personal expressivity associated with authorship in avant-garde or independent films. Although the South Korean film industry centered in Seoul’s Ch’ungmuro district has been consistently market-driven (rather than government subsidized in the manner of, for example, the German or Taiwanese New Waves), its structure has been unstable, oscillating between the proliferation of small, more or less independent studios and government attempts to control these by forcing them into conglomerates. The absence of a stable infrastructure is commonly bemoaned by Korean critics, in terms such as “over the course of its 70-year history … the Korean film industry has not established a systematic or organized industrial structure for itself”,1 especially since government censorship inhibited whatever ideological flexibility or variety the dispersion of production might otherwise have allowed. The first break in this control occurred in the mid-1980s, during the Minjung movement, when a populist alliance of workers, peasants, and factions of the middle class joined to oppose the authoritarian state, leading to a liberalization of the political climate and eventually to a democratically elected government.2 The cultural component of minjung included a generation of young filmmakers who emerged from the university cine clubs to create an underground, agitational cinema, known as the “small-film movement” (chagŭn yŏnghwa undong). Some of these activists subsequently founded their own small companies, allowing them to explore political themes in the often very illustrious features that have gained international recognition as the Korean “New Wave”: Park Kwang-su’s To the Starry Island (Kŭ sŏme kago sipda, 1993) and A Single Spark (Arŭmdaun ch’ŏng’nyŏn Chŏn T’ae-il, 1995) are outstanding examples.3 The authorial expressiveness allowed by this mode of production emerged, however, in the shadow, and often within the stylistic vocabularies of Im Kwon-taek’s earlier auteurist attempt to fashion a Korean art cinema capable of addressing national issues, one that was made under entirely different and fundamentally circumscribed industrial conditions.

Im has only occasionally had anything like the autonomy of the New Wave directors. During the 1960s and 1970s, he worked for small, usually short-lived studios that were dependent on immediate market returns, and generally not able to sustain long-term commitments of the kind that allowed an innovative directorial style to mature.4 But still, they had more in common with the director-driven period of the silent American cinema than with the producer or package-driven systems that replaced it. In the productive system where Im learned his craft, once topics were approved by the studio, directors generally had immediate and more or less complete responsibility for all stages in production – writing, photography, and editing, as well as directing. In this situation, where industrial genre production itself to some degree resembled Western art cinema, Im was able to develop the range of skills that makes the idea of authorship credible later in his career when he was able to choose his own topics.

Other specifically Korean conditions shaped his development. A revision to the motion picture law in 1973 giving the producers of a “quality” film more privileges in importing Hollywood money-makers coincided with Im’s desire to shift the direction of his work, and he quickly became known as a director of “quality” films. And the relaxation of censorship in the 1980s allowed him to raise, if not deeply to probe, previously-proscribed political issues, though typically in historically-distanced allegorical form: the story of the nineteenth century Tonghak nativist uprising, Fly High, Run Far (Kaebyŏk, 1991), for example, was read as referring to the contemporary student movement. But undoubtedly behind Im’s emergence as a singularly prolific and distinctive director was the length and success of his studio work and the unusual range of responsibilities it centralized in one person. He had already made fifty features in this system when, in 1973, a crisis of conscience set him on the path to the art film. “One day I suddenly felt as though I’d been lying to the people for the past 12 years. I decided to compensate for my wrongdoings by making more honest films”.5

After this crisis, which Im has described in several interviews, he envisaged his subsequent career in two streams. In return for his continuing to make genre works for mass consumption, his producers would allow these to subsidize his “honest” films, without expecting them all necessarily to make a profit. The distinction between the two streams turned out to be anything but categorical. The very profitable genre action film, The General’s Son (Chang’gun ŭi adŭl, 1990) and its sequels contain many motifs in common with the art films considered here, while Im’s “honest” films still mobilize the hoariest melodramatic effects. And Sopyonje (Sŏp yŏnje, 1993), Im’s masterpiece and the most fully realized of his personal undertakings, which he never expected to be a commercial success, turned out to be the most profitable domestic film in Korean history until the blockbuster Shiri (Swiri, Kang Je-gyu, 1999). But the arrangement did allow Im to clarify for himself a specific project: in the “honest” films he would confront the manifold traumas of Korean history, and in doing so he would create a specifically Korean art film style.

Since World War II, national art film styles have been conceived in the interplay between deconstructions of the languages of the classic Hollywood cinema and some combination of primarily two other frames of reference. First, the languages of cinemas constructed against capitalism, notably the socialist realisms adopted from the Soviet models in the People’s Republic of China, Viet Nam, and North Korea or the socialist modernisms developed especially in Latin America. Second, the languages of precolonial domestic cultural practices as adapted to the medium of film. The first alternative was categorically unavailable in South Korea in the Park Chung-hee [Pak Chŏnghui] regime in the 1960s and 70s when Im was coming to maturity. During the consolidation of his stylistic strategies and indeed of his fundamental conception of what a film could be, domestic repression, militant anti-communism, and the demonization of North Korea, anathematized any gestures toward socialist realism or the revolutionary Third Cinemas. By the minjung era, when loosening censorship allowed both directions to be explored in the short-film underground, Im was already fifty years old, and successfully entrenched in his own project that had perforce been organized in quite different terms. Of necessity, those terms had been developed out of the other possibility. With no access to a direct critique of capitalist culture per se, Im’s address to Korean modernity was negotiated in respect to precolonial national culture.

For East Asian cinemas generally, traditional theater has been the most important of such resources. The very first film made in China, for example, Dingjun Mountain (1905), was an adaptation of scenes from a Beijing opera. More recent Chinese films, otherwise as disparate and made in as radically different political conditions as The Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin, 1961), Two Stage Sisters (Xie Jin, 1964), Peking Opera Blues (Tsui Hark, 1986), Woman Demon Human (Huang Shuqin, 1987), Good Men, Good Women (Hou Hsiao-hsien,1995), and Farewell My Concubine (Chen Kaige, 1993) attest to opera’s ability to supply stylistic alternatives to U.S. narrative forms. Though Sopyonje concerns a traditional operatic form and though precolonial dramatic and ritual forms were refurbished during the minjung cultural movement, theater has not generally supplied such a fundamental resource for Korean cinema. Im’s oeuvre as a whole is, then, notable for his search through non-theatrical pre-cultural forms to ground the language of a modern Korean cinema, and in several of his best films traditional cultural practices supply metaphors and models for his own aspirations.

Of Im’s films about art, Sopyonje is the most comprehensive. The p’ansori singer, Yu-bong, and especially his adopted daughter, Song-hwa, are proposed as exemplary Korean artists, who attempt to sustain a specifically Korean culture against its debasement, neglect, and the encroachments of foreign media. In Mandala (1981), the protagonist expresses his dissatisfaction with the indifference to worldly suffering that he perceives in traditional Buddha images by carving his own primitive, agonized figure. And in Festival (Ch’ukche, 1996), Im’s negotiation between Confucian tradition and contemporary culture is explicitly inscribed in the two roles of the protagonist, Chun-sŏp: on the one hand, he is a novelist who has made his career by writing about his family; on the other, a dutiful son who, on his mother’s death, presides over the rituals of a traditional funeral, which the film presents in elaborate ethnographic detail. Bringing together the several narrators who recount the widowed mother’s heroic story of raising her seven children, these rituals restage the national question in the form of an allegory of the family, one that explores the terms by which its black sheep may be reintegrated into it. And the funeral ceremonies are interwoven with further dramatizations of the family in other mediums: Chun-sŏp composes a children’s story of his mother’s aging that is presented in a highly artificial film-style utilizing digital technology; and his exploitation of his family in his own art is explored in critical reviews by a young journalist from a literary magazine.6

Such a use of multiple narrators subtends Im’s distinctive formal innovations. Omniscient linear narration is replaced by extended, sometimes multiply nested, subjective flashbacks to produce a structural sophistication matched only by Hou Hsiao-hsien of contemporary fiction filmmakers. In Im’s best films, especially Mandala, Sopyonje, and Festival, the subjective narrators do not contradict each other and thereby mobilize some humanist ontological uncertainty in the manner of, say Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950), the locus classicus of this technique. Rather they fragment the narrative into tesserae that in editing the filmmaker recombines to make thematic arguments, turning narrative into argument, histoire into discourse. But Im’s use of the figure of the artist to investigate questions of national identity was first developed in a formally simpler film, one made at a low point in South Korean cinema mid-way between the golden age of the 1960s and the mid-1980s renaissance. In The Genealogy (Chokpo, 1978) – the work in which he himself believed he first successfully “reflected a personal style”7 – he turned to ceramics, one of the mediums of Korea’s greatest cultural achievement, to limn the terms of a postcolonial cinema.

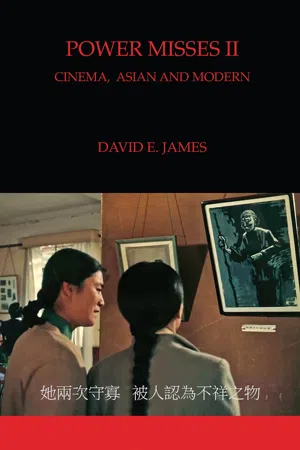

The Genealogy is set in the late-1930s during the most oppressive phase of the occupation, when attempts to extirpate cultural difference included forcing all Koreans to take Japanese names. Believing in the sanctity of his family line, Sŏl Chin-yŏng, a Confucian clan patriarch, refuses to dishonor his ancestors by denying his Korean name. The negotiations between him and the colonial administration are carried out by a young Japanese, Dani, who is also a gifted artist. Recognizing the accomplishment of Dani’s genre painting in classical styles, Sŏl welcomes him into his home, more as a son than as an invader, and the signs of a romance between Dani and one of Sŏl’s daughters, Ok-sun appear. Dani also experiments in modern idioms; he makes a pencil sketch of Ok-sun, and she accompanies him as he tries to paint the Korean countryside in oils (see figure 1.1). Meanwhile Sŏl attempts to solve his predicament by a linguistic sleight; he simply takes the name that is the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters that form h...