![]()

1

The PM, the Poet and the Push

I had several faces because I was young and didn’t know who I was or wanted to be.

Milan Kundera, The Joke, 1967

OF PROPHECY AND COSTERMONGERY

ALFRED DEAKIN WAS A CHILD OF PROPHECY, HIS coming foretold by an ancient gypsy woman encountered by Alfred’s father, William, in the west of England. The wizened crone predicted that William would meet and fall in love with his future wife within weeks, that they would travel to the other side of the globe, and that the new Mrs Deakin would bear him two children – standard ancient gypsy woman schtick.

And lo, it came to pass that William, bearing gifts of apple, cabbage and turnip, did travel to the place that is called Abergavenny in the Kingdom of Wales. There he came upon the maid Sarah. And William said unto Sarah, ‘Will you marry me?’ And Sarah said unto William, ‘Sure.’ Then did William and Sarah journey even unto the ends of the earth, to a place of sin and darkness called Adelaide, where William begat Catherine. And the Spirit came upon William and called unto him, ‘Go ye forth to the lands of the tribe of Melbourne.’ William did as the Spirit bade and there, in the place of the Melbournites that is called Fitzroy, he begat Alfred. And it was good.

William Deakin was a humble costermonger when he met Sarah.1 Costermongers sold fruit and vegetables on the streets, usually from a wheelbarrow. Some, like ancient gypsy women, were travellers – monging their costers by horse, pony, donkey or goat cart.2

Prophecy and costermongery had led William Deakin to Australia. Prophecy would guide William’s only son, Alfred, and raise him to the prime ministership of Australia. Costermongery would guide Australians in fashion, language and the arts – and in developing a national identity – for it is Australia, not Britain, that is truly a nation of grocers.

ALFRED DEAKIN’S SCHOOL DAYS

Alfred Deakin was named after Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the poet laureate of Great Britain and Ireland. Both his parents dabbled with verse, and poetry would become one of Alfred’s great loves.

By the time of Alfred’s birth in 1856, William had abandoned his barrow for a stagecoach and vegetables for Victorians, transporting the latter from Melbourne to the Bendigo goldfields. He would rise through the coaching ranks to become the Victorian manager of Cobb & Co, nineteenth-century Australia’s largest land transport company. Alfred Deakin’s upbringing would be comfortably middle class.

And odd.

Alfred was packed off to boarding school at the unusually young age of four. Even more unusually, he attended Kyneton Ladies’ School, an institution that taught young girls how to be young ladies (i.e. chaste, domesticated and cultured). As the only boy among dozens of girls, he was cossetted and encouraged to be heard, not just seen – a ladies’ school first.

At the age of seven, the aspiring young lady found himself at the all-male Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. Australian grammar schools were modelled on British public schools and, during Deakin’s school days, were the sole providers of secondary education.3

Alfred didn’t make a good first impression at Melbourne Grammar. The other boys teased him for his girlish ways and one of the masters described him as ‘the most incorrigible vexatious restless and babbling creature I ever met’. Alfred performed poorly, later admitting that he’d been ‘an incessantly restless, random and at times studiously mischievous pupil’.

Alfred escaped the humdrum of class through daydreaming. He loved books and haunting public libraries, and seeing Sir William Don performing in drag sparked a lifelong passion for the theatre.4 Alfred, who lacked the practical skills of his father, was definitely more arts than crafts.

The young drag fan progressed to Grammar’s upper school and applied himself to his studies to please his favourite master, John Henning Thompson, brother of the two sisters who’d run Kyneton Ladies’. Alfred later recalled Thompson as ‘over 6 feet, handsome as Apollo, voice like a bugle, eyes beautiful as a woman’s … His influence over me was the most potent yet formed.’

The pliable young man was also shaped by his headmaster, Dr John Bromby, a clergyman who rose early, chopped wood for exercise, sat down to a spartan breakfast, lectured boys on moral living, encouraged their participation in organised games, sat down to a spartan dinner (definitely no alcohol) and retired early for the night, so that he might wake refreshed to do exactly the same again the following day.

Bromby was a Muscular Christian. Muscular Christians believed that manliness was next to godliness and that Christian men should work out more because Jesus was buff.5 They were ascetics who insisted Christian men should preserve their God-given bodies by not abusing them with anything enjoyable, for the degradation of a body made in God’s image was an assault on God Himself.6 The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) helped spread the doctrine of looking hot for Christ around the globe by encouraging young Christian men to exercise and developing new manly sports, including basketball and volleyball.

The Muscular Christian movement, which began in the mid-nineteenth century, was popularised by two English Christian socialist writers, Thomas Hughes and the Reverend Charles Kingsley.

Hughes was a lawyer, judge and politician who championed workers’ cooperatives and the legalisation of trade unions. His works included Notes for Boys, True Manliness and The Manliness of Christ, but today he’s best remembered for Tom Brown’s School Days, in which Tom, an unacademic but athletic pupil at the elite Rugby school, bests the school bully, Flashman, and develops into a manly young man who does not cheat on his homework, says his nightly prayers and is jolly good at ball games.

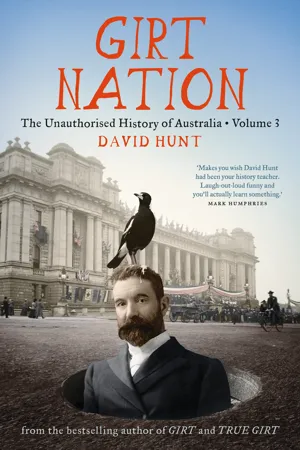

FIG. 1: THE YOUNG MEN OF MELBOURNE GRAMMAR KNEW IT WAS FUN TO STAY AT THE YMCA.

Kingsley was a Church of England clergyman, Cambridge history professor, novelist and poet who championed workers’ cooperatives and the liberal education of working-class men. He was also chaplain to Queen Victoria and private tutor to the Prince of Wales – nice work for a socialist, if you can get it.

Kingsley believed the British royal family were descendants of the Norse god Odin, which might explain the muscularity of the superior ‘Norse-Saxon race’, if not the Christianity. Kingsley didn’t like Italians, Turks, Jews, blacks or Americans. Poor Irish Catholics were ‘white chimpanzees’ and Catholics more generally were slaves to effeminate priests who couldn’t relate to women in the manly way God intended. Effeminacy, Kingsley asserted, had also weakened the Church of England. There should be no place in the clergy for sissies – just cissies, born men who were born leaders and proclaimed their masculinity to the world.

Kingsley is today best remembered for his children’s novel The Water-Babies, in which Tom, a young chimney sweep, drowns after being chased from a rich girl’s house and awakens as a 3.87902-inches-long aquatic cherub whose moral education is completed while living in a commune of other tiny aquatic cherubs, and who saves the soul of his also-drowned former master, for which he is returned to life and becomes a great industrialist and scientist.7

Kingsley and most early Muscular Christians were ‘broad church’ liberals who reinterpreted Christianity according to personal experience and reason. A friend of Charles Darwin, Kingsley championed the theory of evolution, arguing that God had ‘created a few original forms capable of self-development’.

Dr Bromby included evolutionary theory in Melbourne Grammar’s curriculum, and Alfred Deakin, with his inquiring mind and desire to reconcile his spirituality with his observations, integrated this ‘new science’ into his Christian faith. He believed that God had set the wheels of the universe in motion and then taken a back seat, allowing scientifically observable processes to keep those wheels spinning.

Alfred also embraced Dr Bromby’s regimen of self-discipline. The impressionable schoolboy swore off alcohol, coffee and tea, and became a strict vegetarian. Alfred’s vegetarianism was motivated by both his commitment to temperance and his belief that animals had rights, not the least of which was the right not to be eaten.8 Alfred also took up vigorous morning exercise, which became a lifelong habit, although he disdained the organised games that were of growing importance to Muscular Christians and Australians.

Marching was more Alfred’s thing. He lied about his age to join the Southern Rifles, a volunteer regiment that embarked on a recruitment drive when Britain withdrew the last of its troops from the Australian colonies in 1870. The Rifles were warrior poets and Alfred joined their debating society, learning to wound with weapons and words alike.

Alfred had become a well-rounded if tediously earnest young man. In 1871, at the age of fifteen, he finished school and passed the exam to study law at the University of Melbourne.

BARTY AND THE BANJO

Rose Paterson gave birth to a healthy baby boy at Narrambla Station, near the New South Wales town of Orange, on 17 February 1864. The baby’s birth certificate recorded his name as Baby, suggesting that Rose and her husband, Andrew, were very literal people. He was later christened Andrew Barton Paterson, but everybody called him Barty.

The Patersons were descendants of John Petersen, a Scandinavian who’d changed his surname after moving to Scotland. They were into sport, horses and losing vast sums of money, a common Australian trifecta. Barty’s grandfather Captain John Paterson was a champion curler.9 John Paterson, another relative, bred the first Clydesdale horses. And Barty’s ancestor Sir William Paterson convinced Scotland to invest 20 per cent of its money to establish a colony in Panama – the colony failed and Scotland went bust, forcing it to accept union with England.

Barty also had poetry in his veins. Captain Paterson wrote verses about his adventures in India, while Barty’s grandfather Robert Barton married Emily Darvall after reading her poems aboard the ship they shared to Australia. Barty’s early childhood was spent at Buckinbah Station, where he hung out with Jerry the Rhymer, an old convict shepherd and balladeer.

Barty’s idyllic years at Buckinbah were interrupted by a broken right arm, which his mother diagnosed as teething. Rose treated the break by slicing Barty’s gums and burning him behind the ears in an attempt to drain toxins from his body. This was far less dangerous than standard teething treatments – alcohol syrup, laudanum (a tincture of opium) or chlorodyne (a tincture of opium with some cannabis and chloroform thrown in for good measure).10

Barty’s break was not detected until he rebroke his arm after falling from a horse. He snapped it again at the age of twelve and was left with a permanently shortened and weakened limb. Rose, on the basis of no evidence whatsoever, blamed Barty’s Aboriginal nurse for the original break:

That horrid Black Fanny must’ve been climbing trees with him or something of that sort and never let on to us for a moment that anything happened to the child.

Aboriginal women evened the ledger when the accident-prone Barty asked Nora Budgeree, a young Aboriginal girl, for a spear-throwing demonstration. With uncanny accuracy, she threw the spear through his leg.

The Patersons’ curse of losing vast sums of money struck when Barty was five. Andrew senior lost the farm (and two others he owned) when a failed Queensland property venture bankrupted him. Andrew remained station manager at one of his properties, Illawong, a glorified servant on what had once been his own land. He hit the bottle and took laudanum for back pain, slipping into an addict’s depressio...