- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

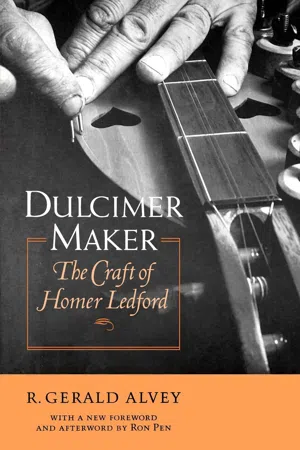

Dulcimer making has long been considered an art. The exquisite design is also functional, and the best instruments sound as beautiful as they look. Homer Ledford, a legend among dulcimer makers, is known for his innovative but traditional craftsmanship. A biography and a step-by-step guide to dulcimer making, this classic book illuminates and celebrates the work of a master craftsman, musician, and folk artist. This new edition presents a foreword by Ron Pen, director of the John Jacob Niles Center for American Music at the University of Kentucky, and an enlightening afterword featuring a conversation with Ledford. In an era when Americans are rediscovering their musical roots, Dulcimer Maker offers a unique look at a bluegrass legend.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dulcimer Maker by R. Gerald Alvey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

III

THE LEDFORD DULCIMER IN CONTEXT

Homer and his dulcimer craft are inextricably grounded in and bounded by the sociocultural, psychological, socioeconomic, and political milieu of American society. Thus it is impossible, from a scholarly perspective, fully to appreciate the origins and the evolution of the Ledford dulcimer without first acquiring some understanding of the cultural contexts, or systems, in which we as Americans live.

Operating within our modern industrialized society are three systems of culture identified by various scholars as folk culture, popular culture, and elite culture.1 All three systems have influenced and continue to influence Homer’s craft in various ways, although the influences of folk and elite cultures probably have been more noticeable than those of popular culture. In order to appreciate and understand the contribution of each of these categories to Homer Ledford’s development as a craftsman and consequently to his dulcimer craft, a brief discussion of the nature of culture, as well as a brief delineation of the three systems is essential.

In essence, culture is everything that a human being is, does, and creates beyond the biophysiological aspects of being a human being; however, the manner in which we attend to biophysiological processes is also cultural. Culture is essentially a process, or a mode, or a system, both of acquiring knowledge or learning and of demonstrating or expressing that knowledge and learning—the values, attitudes, mores, tendencies, preferences, proclivities, beliefs, sophistications, and so on that govern one’s life. This conception of culture is particularly crucial to an understanding of folk culture, as folk culture—and by extension folklore—has for too long been defined primarily in terms of group. It is true, of course, that the people who are integral to the folk cultural process may constitute a group, but to define folk culture—or folklore—by utilizing group as part of the defintion is both erroneous and misleading. This is not to say, of course, that groups—formed for whatever reason—have no folkore; all groups “possess” folklore or, rather, have folk culture contributing to their overall makeup; likewise, all people “have” folk culture contributing to their complex identities, but one person may belong to several groups in today’s complex society, thus complicating matters for the observer or analyst. To be more exact, people actually do not “have” or “possess” “culture;” rather, all people, and every group, learn and retain knowledge and share, express, and perpetuate it in what we see as three basic manners or systems—processes—that we call folk, popular, and elite culture; and the sociocultural essence of all people and all groups is composed of an intricate complex of all three systems.

In delineating the differences between folk, popular, and elite cultural processes or modes, it is essential first to understand that no one system is exclusive of any other; rather, in our modern complex society, there is constant integration of cultural modes. Consequently, as indicated earlier, a boundary cannot be drawn around a group of people in an attempt to identify that group as folk, popular, or elite; however, it is possible to state that a groups’ activities or products reflect at any given time predominantly either elite, popular, or folk culture. However, such analysis must be made for each group phenomenon each time it occurs or exists, as various changes can alter the cultural nature of a phenomenon. It must be further remembered that no group today manifests only one set of cultural characteristics exclusively; for example, a coliseum concert by a bluegrass band (predominantly popular culture) will reflect many folk characteristics both in musical compositions and playing style, yet the performers might have learned music via formal music instruction (elite culture), and certainly the knowledge of how to construct most of the instruments they play is elite cultural knowledge. No group in modern complex society is enclaved or sheltered to such an extent that its cultural dimensions are exclusively those of any one of the cultural systems; rather each group will reflect aspects of all three cultural systems to some degree, although usually one cultural system will be predominant.

The same is also true for individuals. Indeed, the entire cultural dimension of even one individual, such as Homer, existing as he does in our modern complex society, necessarily comprises all three cultural processes. A given individual—say, by virtue of his occupation—may be considered predominantly an adherent of either elite, popular, or folk culture; at the same time, the other two systems will, to a considerable degree, also contribute to that individual’s overall sociocultural identity. For example, Homer, by virtue of his occupation as a dulcimer maker and his heritage as a folk craftsman, without doubt is seen as a folk-culture-oriented individual. Yet he sometimes uses aspects of popular culture to market his dulcimers, and certainly mass tastes and interests have affected his craft. Homer and his craft have been affected by elite culture, too, especially via his institutionalized training in industrial arts. Only by examining a specific sociocultural phenomenon in terms of its origins, past influences, and contemporary contexts can one determine at any given point in time and place whether that phenomenon is predominantly folk, popular, or elite. With these reservations, then, a delineation of the characteristics of the three modes or processes of culture present in modern society follows.2

The system of popular culture is predominant in our society; it is the most widespread and the most adhered to by the majority of people. Elite and folk culture are less pervasive systems. The continuing dominance of popular culture in our society is probably assured because its channels of transmission are the all-pervasive and perennially popular mass media: television, radio, newspapers, magazines, motion pictures, mass marketing, and so on. Popular culture is created primarily by commercial interests—advertising people, A&R (artists and repertoire) people, journalists, business people, and such—for the primary purpose of making money as quickly and on as large a scale as possible; consequently, popular culture is directed toward the anonymous, heterogeneous majority, the masses, the “consumers” of our society; it is designed to prompt people to accept and buy various commercial products: cosmetics, clothing styles, records, soaps and so on.

In contrast, the elite cultural system is created and perpetuated by the so-called intelligentsia: the academicians, the politicians, the “experts” and scholars of the various learned disciplines. Elite cultural processes are usually transmitted via formal, institutionalized, professional, and educational programs and are directed to an individualistic, heterogeneous minority, which nevertheless can be very much a clique and even worldwide in scope. Elite culture is designed both to perpetuate the “tried and true” and to provide opportunity to create anew, to make new discoveries, in whatever field. Not only does elite culture retain and perpetuate its traditional knowledge but a primary purpose of elite culture is to evoke a personal response in its devotees and often to shock them into new awarenesses, new perceptions, ideas, realizations; therefore, progress is often the key word, demanding a constant search for new knowledge.

Although it may sound trite, folk culture nonetheless is probably best described by paraphrasing Abraham Lincoln: it is a culture of the people, by the people, and for the people; it is, to use another hackneyed phrase, grass-roots culture. The system of folk culture is created and perpetuated by the people themselves and transmitted from individual to individual via social situations that are relatively informal, unorganized, personal, intimate, usually noncommercial, and nonofficial; often the folk cultural mode of communication is that of imitation. Folk cultural knowledge, processes, or modes are absorbed by a sort of sociocultural osmosis afforded by a personal intimacy, over a relatively long period of time, between the receiver of the culture and people who already express it. Major purposes of folk culture are to teach models for living and to express humanity at society’s relatively informal, unofficial level.

A brief illustration of these three systems of culture operating simultaneously but more or less independently can be found in cookery. Mass-media-provided recipes (in magazines, in newspapers, on boxes and cans of food products) and health hints (for example, margarine and vegetable oil advertisements) are products of popular culture. Home economics or cooking classes in academic or institutionalized settings and diets provided by medical doctors are illustrations of elite cultural processes. Folk culture includes everything not learned about cookery from popular and elite culture—that is, the knowledge about foods and cooking and eating that one acquires from family and friends. In essence, folk culture constitutes all that one learns other than from classrooms, museums, journals, textbooks and the like (elite culture processes), other than from mass media—radio, TV, movies, comics, rock concerts, newspapers, and the like (popular culture sources).

It should be understood, however, that it is possible to communicate elite knowledge via mass media, public educational television being a prime example. Yet it is not possible to communicate folk culture via mass media; folk culture performances or demonstrations of knowledge require natural contexts, and the artificial contexts of mass media inhibit, distort, and often even destroy the very nature of the folk cultural process. I am fond of saying that folk cultural communication requires at least two warm bodies, not one warm body and one warm tube. If a folk singer’s performance is broadcast on television, the most one can say is that it is a media representation of a folk-culture performance. (This is not to say, on the other hand, that information garnered from either elite or popular cultural presentations cannot be adopted and adapted by the folk cultural process; parodies of all kinds exemplify such adoptions and adaptations.)

Likewise, it is impossible to capture most forms of folk culture in other media; it is impossible to have, for example, a folktale “in” literature. Folktales are more than just words; they are, as Robert Georges has discerned, folk cultural “storytelling events.”3 To share in that event, one needs to be personally present when the tale is told, so that one not only hears the words but also appreciates and comprehends how the words are used, where, when, by whom, to and for whom, and why they are used. One needs to experience the communal effect of the live communicative process; that is a folktale; that is folk culture, in context and in process. Any literary scholar will be quick to admit that not even dialect can be represented accurately in print; moreover, print cannot possibly convey intonation, modulation, timbre, nuance: the paralinguistic and nonverbal dimensions of what we call storytelling. Folktales in print are merely written representations of only part of the linguistic aspects of storytelling events. Folk cultural communication occurs only when it takes place in natural context. Even some literary scholars recognize that “the value of the study of the folklore . . . depends entirely on the context and the critical implications of the subject.”4

Similarly, then, a folk craft cannot be communicated in totality in print, or even on videotape. This study, consequently, while attempting to describe and to discuss Homer Ledford’s dulcimer craft, cannot hope to render to the reader the totality of the craft itself. Through such media as print or even videotape it is impossible for a viewer to see every angle of a process, to assess precisely the amount of pressure to place on an object in a phase of its delicate construction, to ascertain the “just right” angle of a pocketknife or chisel, to feel the wood or other materials—to know by personal immediate presence everything one must know to comprehend the craft and the craftsman and how they meet to produce art.

Thus far this delineation of the characteristics of popular, elite, and folk cultural modes has primarily emphasized the acquiring of cultural knowledge rather than the demonstration of that knowledge, although, of course, acquiring cultural learning and expressing cultural learning are in reality two sides of one coin. Because this study deals specifically with the production of a craft-art form and its artist-craftsman, it will perhaps be most pertinent to discuss the demonstration or expression of each of the three cultural systems in terms of art and craft products, and their artists-performers-makers.

In order to achieve success—that is, to make money—in the popular-culture system, artists-craftsmen-performers and their products (especially the latter) must be faddish, innovative, and able to provide their mass audiences with immediately appealing, easily digestible entertainment or diversion; the audiences of the mass media are, for the most part, passive receivers of popular art forms and will expend little intellectual effort in order to appreciate them. The norms for popular-culture art forms are determined by popular demand, by what will work or succeed with the mass public, by what will be accepted as the “in” thing; few, if any, codified rules govern such art forms. Consequently, popular art is continually changing and necessarily ephemeral; the minute an art product of popular culture ceases to attract the masses, popular culture permits and even demands that such a form be changed, altered, or obliterated; incessant—sometimes frenzied—mass popularity is the ideal goal. Obviously, such adulation can persist for only a relatively brief span of time; hence the continual flux and ephemeral nature of popular culture products. Furthermore, in its efforts to remain continually in vogue, popular culture frequently borrows forms, styles, and modes from both elite and folk culture and then subjects the borrowing to some sort of faddish alteration; hence such hybrids as “folk rock.” This preoccupation with fad and fashion is in sharp contrast to folk and elite art forms, both of which endure over long periods of time.

In the elite-culture system, technical and thematic complexities are a great concern in art forms; as a result, audiences are usually instructed formally in proper “appreciation,” often through so-called music or art or literature appreciation courses. Audiences are expected to ponder and savor each production, to experience it over and over again. Ideally, once an elite art form is created, it does not change; performances generally are attempts to reproduce as exactly as possible the original creation as conceived by its author; one would not, for example, attempt to rework a Beethoven symphony. Rules for both the creation and the performance of elite art forms are often strictly codified; however, within such codified techniques, individualistic variation is usually permitted, allowing authors and artists to develop idiosyncratic approaches to style and content. Consequently, it is possible, for instance, to recognize the works of various given individuals, all of whom might nonetheless by painting within one mode; for example, one can differentiate among the many Florentine masters and identify any one master’s works, yet all such artists are still within the Florentine “school.” Furthermore, all of these elite art forms, once created, persist through time and space. Maintained a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Introduction

- I. Homer Ledford: The Man and Craftsman

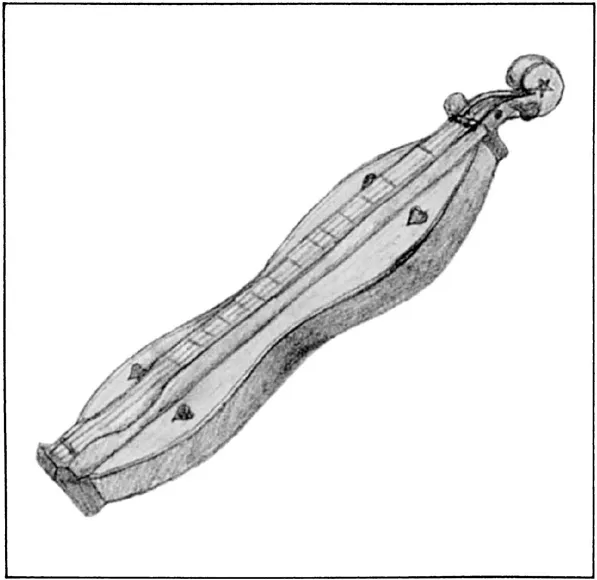

- II. The Anatomy of the Ledford Dulcimer

- III. The Ledford Dulcimer in Context

- Afterword

- Audeography

- Notes

- Index