![]()

III

Complex Industries/Industrial Complexes

The Military and Security Industry: Promoting Europe’s Refugee Regime

Mark Akkerman

Building on long-standing policies, the European Union (EU) has escalated its militarization of border security since the start of the so-called refugee crisis, in April 2015.1 While EU border and migration policy developments have had horrific consequences for refugees, they have meant more profit opportunities for the military and security industry. Large European companies are the big winners.

Since 2015, the use of military means and/or personnel for border security has skyrocketed. Several EU member states—including Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Macedonia, the Netherlands, and Slovenia—have deployed armed forces at their borders to assist in border control and security. Austria, Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Macedonia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey, and Ukraine have each built border security fences adorned with all kinds of detection and surveillance technology.

Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, has continued and sometimes intensified its military border security missions in the Mediterranean, which include Poseidon (Greece), Themis (Italy, a follow-up to Triton), and Hera, Indalo, and Minerva (Spain). The EU has also launched Operation Sophia, its own military-run European Union Naval Force Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR MED) operation on the Libyan coast, intended to stop refugees from attempting to cross the Mediterranean. Sophia is the first overtly militaristic response to refugees on an EU level. In June 2016, the operation mandate was extended to include the training of members of the Libyan Coast Guard and navy personnel.2 Standing maritime NATO missions in the Mediterranean assist Operation Sophia and other border patrols in the Aegean Sea.3

The importance the EU attaches to security at its external borders is reflected in the financial support it provides to its member states and third countries to strengthen border security and control. This funding flows largely through three mechanisms: the Schengen Facility, the External Borders Fund, and the Internal Security Fund—Borders and Visa. Through these programs, some €4.5 billion will have been dispersed to EU member states from 2004 to 2020.4 These funds have backed a wide array of activities and purchases, including vessels, vehicles, helicopters, IT systems, and surveillance equipment.

In September 2016, the British think tank Overseas Development Institute made a “conservative estimate … that at the very least, €1.7 billion was committed to measures inside Europe from 2014 to 2016 in an effort to reduce [migration] flows.” The report added that this figure “presents only a partial picture of the true cost.” Furthermore, “in an attempt to deter refugees from setting off on their journeys … since December 2014, €15.3 billion has been spent” in third countries. Again, the quoted figure represents “a very conservative estimate.”5

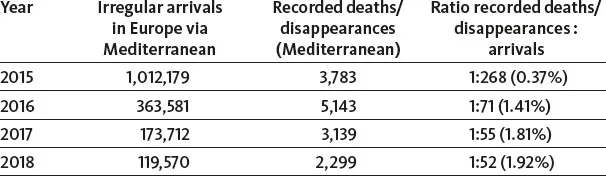

Such policies cause shifts in migration routes: when one route is almost closed off due to increased securitization, refugees are forced to look for other, often more dangerous, routes into Europe. Since the November 2015 EU migration deal with Turkey, for example, the predominant migration route to Europe became the sea crossing between Libya and Italy. This is known to be a hazardous route, and a much higher proportion of refugees died during attempted crossings subsequent to the deal than had perished in previous years.6

The militarization of border security is not limited to EU borders. Through “externalization of borders” initiatives, the EU uses third countries as forward border posts to stop refugees on their way toward Europe. Hence EU assistance to third countries, mainly in Africa, includes donations of military, security, and biometric equipment. Such support strengthens authoritarian regimes and often leads to more violence against refugees, while also undermining economic development and stability in the affected countries.

The EU’s border externalization priorities are evident in the increasingly central role migration plays in its civil-military (CSDP) missions in Mali and Niger.7 The prioritization of border management within these missions, through training and capacity building, was recognized in the 2016 annual report of the Sahel Regional Action Plan, which concluded that “the three CSDP missions in the Sahel have been adapted to the political priorities of the EU, notably following the EU mobilization against irregular migration.”8

Table 11.1: Migrant arrivals and deaths: Europe via the Mediterranean

Industry Shapes Policies

The arms industry plays a significant role in formulating the EU’s foreign and security policy agenda. According to Martin Lemberg-Pedersen of the University of Copenhagen’s Centre for Advanced Migration Studies, arms companies “establish themselves as experts on border security, and use this position to frame immigration to Europe as leading to ever more security threats in need of ever more [private security company] products”—the very products that these companies sell.9

Large European arms companies have their own lobbyists working in Brussels, while also cooperating with the European Organisation for Security (EOS), the lobbying group of the European security industry. Its primary objective is the development of a harmonized European security market. EOS has identified “border security” as one of the main areas of concern in the field of European security. It has issued papers with recommendations and organized several meetings between industry and EU politicians and officials, including European Commissioners. Military companies—including Airbus, Leonardo, Thales, and Indra—play a leading role in EOS, including in its work on border security and control.

Lobbying—both by the EOS and by individual companies—has been highly successful, foremost, in framing migration as a security problem rather than a political and/or humanitarian concern and, secondarily, in promoting military means as the solution. Concrete proposals with roots in industrial lobbying, such as the establishment of a European border guard and of the EU-wide border monitoring system EUROSUR, eventually found their way into EU policy.10

Industrial influence on EU policy can also be seen in EU security research funding decisions.11 In 2004, for example, the European Commission followed the proposal of a Group of Personalities (GoP) to integrate security research into a large seven-year European Research and Technology (R&T) project, the so-called Framework Programmes.12 This particular GoP was initiated by the European Commission, and eight of its twenty-seven members were representatives of large European military companies and research institutions—many of which turned out to be among the biggest beneficiaries of the new funding.

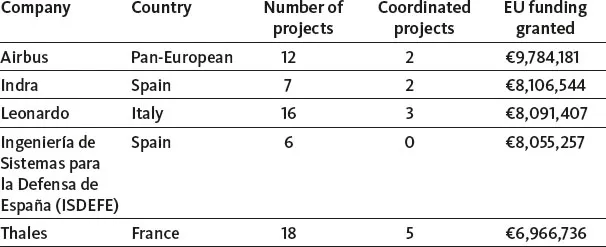

Table 11.2: Major industrial profiteers of EU-funded border security R&D projects, 2002–2016. Companies sometimes have two or more subsidiaries participating in a single project. For example, Airbus companies had a total of thirty-two participations in twelve projects.

(Source: Community Research and Development Information Service)

Profiteers: Making a Killing

Consultancy company Visiongain estimated that the global border security market was worth $18.9 billion in 2016, up from $15 billion in 2015—a 26 percent growth within one year.13 Market Research Future predicts continued market growth, at a rate of 8 percent per year until 2023.14 European arms and technology companies are the major profiteers of the EU segment in this market,15 with Airbus, Leonardo, Thales, Indra, and IDEMIA standing out as the big winners of the refugee tragedy. Cynically enough, Airbus, Thales, and Leonardo are also large exporters of arms to the Middle East and North Africa, feeding and profiting from the very chaos, war, human rights abuses, and repression that fuel forced migration.16

Table 11.3: Profits and revenues of Europe’s largest arms producing companies, 2018

EU border policies, which are focusing ever more on security and militarization, will be a key driver for the anticipated border security market growth. As of October 2016, Frontex has been able to buy its own equipment (rather than using equipment made available by EU member states) and to instruct EU member states on how to strengthen their border security, presenting a further boost for the border security market.17 Since 2017, the EU has also financed military research outright, starting with pilot projects and integrating this research as a new priority in funding cycles from 2021.18 Border security will likely remain an important area of interest.

Recent shifts of attention to the African market is another notable development: with EU pressure and financial encouragement to African countries to strengthen border security, the region is becoming a bigger target for military and security companies. Both Airbus and Thales have explicitly stated that they expect Africa to be the most promising market in the near future, particularly in the field of border security.19

The “Border Security” Profiteers

Airbus

Founded: 2000 as European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company (EADS), merger of DaimlerChrysler Aerospace (DASA), Construcciones Aeronáuticas, and Aérospatiale-Matra; renamed Airbus in 2014

Headquarters: Leiden, Netherlands; Corporate Headquarters: Toulouse, France

Arms producing companies ranking (2018): seventh (world), second (Europe)20

Shareholders: France (11.1 percent), Germany (11.0 percent), Spain (4.2 percent), others (73.6 percent)21

Employees (2019): 133,67122

Lobbying in Brussels (2018): budget €1,750,000–1,999,999 (approximately US$1,893,000–2,163,000), 11 lobbyists (4.75 full-time equivalent [fte])23

Meetings with European Commission officials, November 12, 2014– February 11, 2020: 17624

- Headquartered in Netherlands for tax reasons, most of Airbus’s production takes place in France, Germany, and Spain. Its border security products range from helicopters via communication systems to radar.

- European border guards using Airbus helicopters include Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, Romania, Ukraine, and Slovenia. The purchases by Finland and Romania were EU-funded.

- In 2004, Romania awarded the company a contract for a “Integrated System for Border Security,” bought to meet EU border security requirements before becoming an EU member in 2007. The deal, worth €734 million (approximately US$1 billion), prompted a corruption investigation by the Romanian National Anticorruption Directorate when allegations of bribes paid to Romanian officials surfaced.25

- Signalis, a joint venture of Airbus and Atlas Elektronik (Germany), has also sold border security systems to France, Spain, and Bulgaria.

- The German government purchased an array of Airbus equipment to donate to Tunisia for border control purposes.26

- In 2017, Airbus sold its DS Electronics and Border Security division to the American private equity firm KKR & Co. for approximately €1.1 billion (approximately US$1.25 billion), maintaining a 25.1 percent minority stake for “a limited number of years post-closing.”27 This division continues to operate under the new name Hensoldt.

Leonardo

Founded: 1948, as Finmeccanica; renamed Leonardo-Finmeccanica (2016– 2017), and then Leonardo

Headquarters: Rome, Italy

Arms producing companies ranking (2018): eighth (world), third (Europe)28

Shareholders: Italy (30.2 percent), others (69.8 percent)29

Employees (2019): 46,46230

Lobbying in Brussels (2018): budget €300,000–399,999 (approximately US$354,000–472,000), 3 lobbyists (3 fte)31

Meetings with European Commission officials, March 25, 2015–January 27, 2020: 4132

- Italian aerospace and defense company that, like Airbus, supplies helicopters to European border guard agencies. Purchases by Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Italy, Latvia, and Malta were funded by the EU. Other customers include Finland and Slovenia. Its 2016 delivery of two AW139 helicopters to Croatia for border surveillance cost the EU over €30 million (approximately US$33 million).

- In 2005, Poland awarded the Leonardo subsidiary Selex a €30 million contract (approximately US$35.7 million) to build a coastal surveillance system (ZSRN) for the Polish border guard. The company also installed radar on maritime patrol aircraft of the Finnish border guard.

- In 2009, Italy and Libya concluded a deal wherein Leonardo was contracted to build a border surveillance system for Libya. The deal stipulated that Italy and the EU would each pay half of the €300 million (approximately US$417 million) involved. The project was halted when the civil war broke out, but talks about reviving it have been ongoing since 2011.

- Supplies ground stations and drone communications technology to the Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) for NATO.33 US arms producer Northrop Grumman is the main contractor for AGS. Assistance in border control is one of the main aims of this system, which was intended to be in use by 2018 at the Italian Naval Air Station Sigonella, in Sicily.

- In June 2017, Leonardo announced a partnership with Heli Protection Europe (HPE), another Italian company, to provide surveillance and reconnaissance services via drones, including to monitor migration.34

- In 2018, Leonardo was awarded a contract by Frontex for three hundred hours of drone surveillance flights over the Mediterranean.35

Thales

Founded: 1968 as Thomson CSF following the merger of Thomson-Brandt companies with Compagnie Générale de Télégraphie Sans Fil; renamed Thales in 2000

Headquarters: La Défense, France

Arms producing companies ranking (2018): tenth (world), fourth (Europe)36

Shareholders: France (25.8 percent), Dassault Aviation (24.7 percent), others (49.5 percent)37

Employees (2019): 66,13538

Lobbying in Brussels (2019): budget €300,000–399,999 (approximately US$336,000–447,000), 7 lobbyists (2.75 fte)39

Meetings with European Commission officials, March 6, 2015–July 12, 2029: 2440

- French arms and technology company t...