![]()

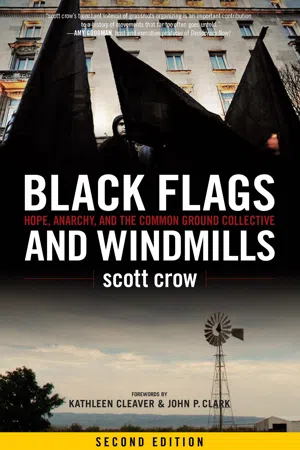

Dream the future

Know your history

Organize your people

Fight to win

![]()

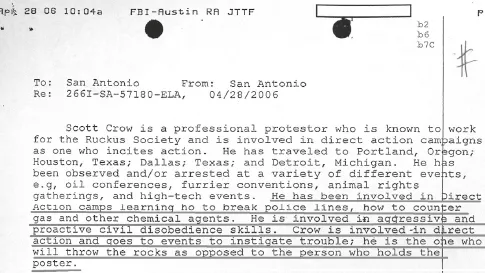

2006 FBI memo that says I use direct action to go to events to cause trouble.

Treasure City Thrift, an anarchist worker co-op I cofounded in Austin, TX, 2006. PHOTO CREDIT: ANN HARKNESS

With Rebecca Solnit, talking about the aftermath of disasters. PHOTO CREDIT: LIZ HIGHLEYMAN

In Austin with Ann Harkness and Robert King, 2009.

Left to right: Jeff Luers, Ryan Shapiro, Will Potter, scott crow.

Original Common Ground Collective cofounders: (left to right) Malik Rahim, Sharon Johnson, scott crow. PHOTO CREDIT: TODD SANCHIONI

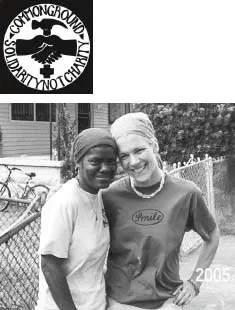

Common Ground cofounder Sharon Johnson and volunteer Hali Stone. PHOTO CREDIT: DAVID AMPERSAND

First distribution center in Algiers neighborhood, 2005. PHOTO CREDIT: JACKIE SUMELL

Unidentified, bullet-riddled dead black male. When I first arrived in Algiers in September 2005, we put the metal on him to cover him up. Who killed him—the police or the white militia? PHOTO CREDIT: JAKE APPLEBAUM

PHOTO CREDIT: CGSTORIES.ORG

Common Ground general assembly, 2006. PHOTO CREDIT: CGSTORIES.ORG

“House of Excellence,” one of the many community Internet/phone access sites set up by Common Ground. PHOTO CREDIT: CGSTORIES.ORG

Signs that were all too common across New Orleans in white areas. PHOTO CREDIT: JACKIE SUMELL

A sign with relevance before and after the disaster. PHOTO CREDIT: JACKIE SUMELL

Soldiers in front of Common Ground’s little blue house in the Ninth Ward, 2006. PHOTO CREDIT: CGSTORIES.ORG

MLK school where volunteers using civil disobedience cut the locks and cleaned out the school, 2006. PHOTO CREDIT: CGSTORIES.ORG

Speaking to a crowd in New Orleans: (left to right) Kerul Dyer, Lisa Fithian, Malik Rahim, and Sakura Kone, 2006. PHOTO CREDIT: CGSTORIES.ORG

Meg Perry, young tireless organizer from Maine who was tragically killed while working for Common Ground. PHOTO CREDIT: CGSTORIES.ORG

![]()

Shifting Culture without Government

DJ Pangburn

I recently spoke to noted anarchist community organizer scott crow about how average people—people with dreams, vision, grit, and motivation-can affect change in a very real and quantifiable way after the vote. This isn’t a playbook for smashing some McDonald’s or Starbucks windows but for taking the fight to communities.

A tired cycle exists in American electoral culture. Every two years we vote for federal representatives and senators, and every four years we vote in the presidential election. Each election cycle builds to a critical mass of ideological recriminations that crescendo on election day. Americans then rather sadly wash their hands of the mess and resolve to do little or nothing to actively make democracy work. There is a relinquishing of the responsibility of democracy to representatives. And as we’ve seen in the last twelve years of bitter partisan divide, it has produced paralysis instead of results. It has popularized politicians who behave more like actors or programmed holograms than actual problem solvers.

Mr. crow has had a roughly two-decade-long résumé of working in community organizing circles, most notably as one of the founders of the Common Ground Collective, one of the largest and most-organized volunteer forces in the post-Katrina wasteland. When W’s buddy “Brownie” (Michael Brown) was botching the FEMA response, and the National Guard was enforcing martial law on New Orleans streets, CGC was busy cleaning out destroyed homes, mobilizing free healthcare, clothing, and food, and otherwise delivering mutual aid to a grateful New Orleans population. Much of crow’s current work involves helping communities build worker cooperatives and local economies horizontally, which is explained in more detail below.

We Are More than Just Voters and Consumers

The voter, says crow, must pass into oblivion. In his or her place must arise the doer, the creator—that person who sees all potential and jumps into action.

Ancient Rome suffered a political paralysis similar to contemporary America. In Rome, voters were mostly irrelevant. Into this political void came the Roman emperors who, while bringing some domestic stability, only hastened Rome’s fall. Whereas the great American political paralysis might be a melancholic moment for this country’s patriots, scott crow sees vast opportunities to do great things. “There are a set of paths in the middle that we haven’t even explored to a great extent in this country,” he says. “The dominant paradigm tells us that we are just voters and consumers with a void of other alternatives. Life—politics, culture, and economies—[involves] more complicated social relationships in this country.” The trick is to be a creator, someone who sees new paths and pursues them energetically. “The [new paths] aren’t always going to be easy,” he says. “But we will be doing them together; block by block and community by community, as needed.”

Asked if voting has any real redeeming value, crow is mostly pessimistic. “Voting is a lot like recycling: if you’re so damned lazy that you can’t do anything else, then at least do that,” he says. “It’s the least you can do. Pulling the lever or throwing something in the correct bin; neither require great effort or thinking, but neither have real impact either.”

Community organizers like crow have no time for political saviors. They are individuals who eschew antiquated democratic politics. Dreamers and doers who depart the political reservation for more unknown trajectories.

“We’ve had this mythology of the Great White Hope, that some great leader who will take us from our chains into the future,” notes crow, a little astonished that so many still buy into the collective democratic hallucination. “When ‘he’ fails—as they always do—we blame the person and not the systems that got us there. We need to look anew at our world and think of the different ways we can engage with the world, our city, our neighborhoods, and ourselves.”

“We have other choices,” he adds. “Why is that we demand choices in MP3 players, sodas, or schools, for example, but not in our economic, cultural, or political systems that affect everything about us and our world?”

Issues Do Not Exist in Isolation

Americans have the tendency to engage issues in isolation. For the extreme (and even the mainstream) conservatives, “socialism,” “immigrants” or “gays” are the viruses corrupting the system—other domestic and international considerations be damned. A matrix of interrelated issues work at one another like a neural network. One cause may have several effects. And that cause may itself be the byproduct of other variables.

“If you want to stop hunger, you can’t just go, Well, I’ll just feed somebody and it’s over,” crow argues. “You start with that and then ask, Why are they hungry? Did they not have access to good schooling? So then we need to fix the schools or create new ones. Did they not have good access to jobs? Then we need to create good jobs with a living wage, dignity, and respect. Or did they have healthcare issues that aren’t being addressed, even just basic stuff? Well then we need to get community clinics in every community so that people can have their basic needs looked at before they become major issues like cancer or diabetes.”

For this sort of education, crow had to look toward more revolutionary movements for this sort of education. “I had to look at what the Black Panthers and the Zapatistas did for their communities,” he says. “I had to look at what the Spanish anarchists did when fascism was taking over. They were inspiring in that they helped their people and rebuilt their world. Those are just political references. In every subculture, whether it’s religious groups, charities, or hip-hop communities, there are examples of people doing things themselves without waiting for government or other people to do it.”

“In what I like to call anarchism with a little ‘a,’ we need to explore ideas of direct action so that we’re not waiting on others to fix the problems,” he adds. “We will do it ourselves. Mutual aid, cooperation, collective liberation—the idea that we’re all in this together. But there also needs to be an awareness that you are in this yourself.” He points out the unvarnished political reality: no leader, party or group is going to do this for Americans. But there is a more salient point. Even if a single leader or political party had this sort of desire, the country is far too big and complex for such national policymaking. They are mere band-aids on gushing wounds. “We need to decentralize and localize to solve the problems around us, while looking to support other communities doing the similar things and connect on larger issues,” he says. “And to do this we have to first look at history.”

Create Localized Economies

“It’s absolutely cliché to say we need to think globally and act locally,” says crow. “But that’s exactly what we need to do while we are creating localized economies (gift, barter, or local currencies), opening the common spaces from the holds of corporate private property (like shopping malls) and becoming neighbors again.”

“We need to know what is happening around the world and share the information, successes and challenges that we face in our communities to help each other,” adds crow. “What happens to a rice farmer in India or a landless peasant in Brazil or a family in Appalachia is of utmost importance to me in thinking of supporting each other.” The internet and social media in particular will help in this flow of information.

Perhaps the most important lesson in the recent trend of localization is that scaling down just might be what saves us. It doesn’t require a singular savior but hundreds of millions, indeed billions of them. Centralized government and corporations haven’t worked for humanity, argues crow. And who would disagree in this second decade of the twenty-first century?

“Centralizing corporations—these giant pyramids with elites at the top—aren’t working out for the rest of us,” adds crow. “And it’s not just the 99%—it’s not working out for any of us, not even some of the elites.”

Government and industry aren’t the only institutions ripe for a downsizing, according to crow—the world’s...