![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Great Panic of 2008

BEFORE THE DENIAL CAME THE PANIC. AND WHAT A PANIC IT WAS.

“I am really scared,” U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson confided to his wife on September 14, 2008, as the Lehman Brothers investment bank disintegrated, sending shockwaves through global credit markets.25 The next day brought Lehman’s collapse, followed a day later by that of AIG, the world’s largest insurance company. Before the month was out Washington Mutual would melt down, registering the biggest bank failure in U.S. history. Then America’s fourth-largest bank, Wachovia, went on life support. A wave of European bank collapses rapidly followed.

So panicked and bewildered were global elites that Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, informed a Congressional committee the following month that he was in a state of “shocked disbelief ” over the failure of markets to self-regulate.26 Small wonder. By the fall of 2008 the global financial system was in full-fledged meltdown. Worldwide credit seized up as financial institutions refused to lend for fear that borrowers would not survive. Stock markets plummeted. Global trade collapsed. Banks toppled. As shaken commentators invoked memories of the 1930s, two U.S. investment bankers openly compared the situation with the Great Depression.27

“Our economy stood at the brink,” Tim Geithner, current U.S. treasury secretary, testified about those weeks. “The United States,” he continued, “risked a complete collapse of our financial system.”28 Canada’s finance minister, Jim Flaherty, echoed this view, stating that the world economy had hovered on the edge of “catastrophe.”29 Catastrophe, indeed.

Over the course of 2008, global stock markets plunged nearly 50 percent, wiping out about $35 trillion in financial assets. All five of Wall Street’s investment banks simply vanished— kaput . But the disease did not stop with the U.S. economy. Banks went under in Ireland, Spain, Germany, the UK, Iceland, and beyond. Nor was the meltdown limited to finance. General Motors and Chrysler both went bust, only to be bailed out and taken over by the U.S. government. And across the meltdown, millions of people lost their jobs, and many of them their homes. Homelessness and hunger soared.

Unfolding into 2009, the crisis tracked the contours of Great Depression of the 1930s. The collapse of world industrial production, global trade, and stock market values was as severe as 1929–30, sometimes more so.30 For the first time in seventy years, world capitalism seemed to have entered a crisis with no clear end in sight.

And for the first time in a very long time, the world’s ruling class lost its swagger.31 Arrogance and ostentation were displaced by fear and trembling. So severe was the capitalist crisis of confidence that in March 2009 the Financial Times , the most venerable business paper in the English-speaking world, ran a series on “The Future of Capitalism,” as if that were now an issue. Introducing the series, its editors declared, “The credit crunch has destroyed faith in the free market ideology that has dominated Western economic thinking for a decade. But what can—and should— replace it?” The next day the paper’s editors opined that “The world of the past three decades is gone.” And one of its column-ists quoted a Merrill Lynch banker who remarked, “Our world is broken—and I honestly don’t know what is going to replace it.”32

So palpable was the sort of fear expressed by Hank Paulson to his wife, so tangible the loss of confidence conveyed by Alan Greenspan’s “shocked disbelief,” that a small but important space opened up for real discussion and debate about our economic and social system. In this environment, even critics of capitalism occasionally found their views solicited by mainstream media.33 “Marx is in fashion again,” declared a Berlin book publisher, describing an uptick in sales of Capital , while in Japan a comic book version of Marx’s greatest work sold tens of thousands of copies.34

It is not hard to see why the crisis generated interest in alternative social and economic perspectives. After all, for decades mainstream economics had denied that such an event was even possible. Clinging to the so-called Effi cient Market Hypothesis (EMH), which insists that markets always behave rationally, the leading lights of the economic profession repeatedly proclaimed that systemic crises were no longer possible. “The central problem of depression-prevention has been solved,” announced Nobel laureate Robert Lucas, in his 2003 presidential address to the American Economic Association. Meanwhile, the originator of EMH, Eugene Fama, haughtily dismissed those who predicted a financial crisis, telling an interviewer, “The word ‘bubble’ drives me nuts”—just as one of the greatest financial bubbles in history was exploding.35 Backed by a profession that denied the possibility of economic slumps, David Lereah, former chief economist of America’s National Association of Realtors, published one of the most absurdly titled books in a very long time, Are You Missing the Real Estate Boom?: The Boom Will Not Bust and Why Property Values Will Continue to Climb through the End of the Decade — And How to Profi t From Them (2005). And the mainstream media, incapable of challenging the established consensus, turned the author into the foremost authority on housing prices, reproducing his views in hundreds of outlets, including the New York Times , the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal.

Little surprise then that the credibility of mainstream economics went up in flames as the crisis deepened. Not only could critics of free market nostrums now find a hearing, but books like The Myth of the Rational Market garnered widespread attention and favorable reviews in the Economist , the Washington Post , Financial Times, and beyond.36 Not that any of this led to a fundamental rethinking within the mainstream itself. Instead establishment pundits, once they conceded that the economy was in crisis, endlessly proclaimed that it could not have been foreseen. It was a once-in-a-century event, they insisted, a bizarre aberration. “Everybody missed it—academia, the Federal Reserve, all regulators,” Alan Greenspan recently claimed—though, as we shall see, this is anything but the case.37 But by endlessly repeating these mantras, ruling class spokespeople and their media friends have been busily creating a structure of denial and mystification meant to close off critical inquiry into what actually happened—and why.

But just as denial is unhealthy for individuals, so it is for groups and societies. To deny or repress a traumatic experience means, as Freud taught us, to invariably repeat it.38 And this is what global elites are in the process of doing. By denying the trauma of the meltdown and their own profound panic, by trying to wipe them from memory, they trap society in a repetitive cycle of trauma and repression. Of course, it is in their interest to do so; they profit from a culture that inhibits critical inquiry and analysis. But the vast majority—those who do not own banks and giant corporations, or multi-million-dollar stock and bond portfolios—need to understand the world in order to change it. And that requires confronting traumatic experiences—especially when jobs, incomes, housing, education, and pensions, not to speak of human happiness and well-being, are at stake. So, let us resist the denials and mystifications and probe the Panic of 2008 a bit more.

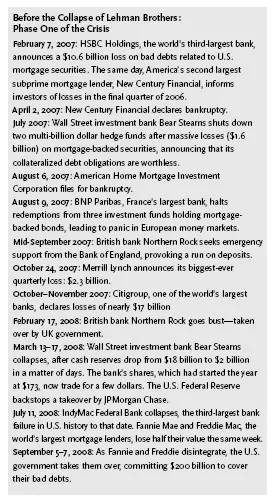

Why Hank Paulson was Scared

Hank Paulson had good reason to be scared on September 14, 2008. Global capitalism was in freefall, as one financial institution after another was taken down by “the most virulent global financial crisis ever.”39With stunning rapidity, eight major U.S. banks collapsed, as did more than twenty in Europe, many of them to be taken over by governments. GM and Chrysler went bust, along with many parts suppliers. Tens of millions of people worldwide were thrown out of work. And no amount of government intervention seemed capable of calming the markets. Despite a full eighteen months of warning signs, from the collapse of hedge funds to huge losses at investment banks, government offi cials utterly failed to grasp the nature or severity of the crisis. On March 28, for instance, Fed chair Ben Bernanke calmly asserted that, rather than undermining the broader economy, mortgage-related problems were “likely to be contained.” A few weeks later, the International Monetary Fund went further, issuing the astonishing claim that “global economic risks have declined . . . The overall U.S. economy is holding up well.”40This was more than deception. It was also stupidity—as we shall see in chapter 4. Government leaders, just like world bankers, truly did not understand what was happening to the world economy. Yet, as the accompanying box, which tracks the First Phase of the crisis, demonstrates, the powers-that-be had received plenty of warning as to what was coming.

At this point, it should have been obvious that something was seriously amiss with the world’s financial institutions. Indeed, it was obvious to a small number of critics and commentators, as we shall see. But because mainstream economics, armed with the Effi cient Market Hypothesis, claimed that markets would quickly self-correct, government offi cials, bankers, and media talking heads kept proclaiming that all was well, or soon would be. To be sure, some of this was just the steady diet of lies and distortions that our rulers feed the people. But much of it was also their own stupidity, their incapacity to see that neoliberal capitalism was profoundly unstable and that its financial structure was coming undone. Had Paulson and the U.S. government brain trust at the Treasury and the Federal Reserve—which included Fed chief Ben Bernanke and then New York Fed president Tim Geithner—actually understood what they were dealing with, they would not have let Lehman collapse. For the disintegration of the New York investment bank triggered Phase Two of the crisis, by far its most virulent stage, sending shockwaves through the global economy that took down banks and at least one government.

The implosion of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, was a truly spectacular event, without precedent in U.S. economic history. Seven years earlier, the collapse of Enron, worth $60 billion, had astounded commentators. But Lehman, valued at $635 billion only five days before it went under, was more than ten times the size of Enron and more than six times larger than WorldCom when it melted down some months after Enron. Most important, it was dramatically more interconnected with the world’s financial institutions. The Enron and WorldCom failures were early tremors, shifts in the fault lines that signaled the quakes to come. The false calm that ensued was broken by the wave of shocks that started in mid-2007. But Lehman’s collapse was the Big One, a tectonic eruption that blew a gigantic hole in the world economy. If Lehman could go down, after 158 years as perhaps “the greatest merchant bank Wall Street ever knew,” then no one was safe.41 Worse, nobody—not Lehman’s directors, not Treasury and Fed offi cials, not savvy investors—could calibrate the scale of the damage.

Because of the increasingly complex financial instruments that had emerged across the neoliberal era, an utterly opaque market had developed in which no one could figure out who owed what to whom. Derivatives, collateralized debt obligations, credit-default swaps, and similar instruments (all of which I explain in chapter 4) might have been profitable for a while, but they were obscure, deceptive and volatile. Built upon fantasies, deceit and nonsensical formulas, the values of these “assets” were impossible to calibrate, particularly as they melted down. “We have no idea of our derivatives exposure and neither do you,” Lehman bosses told Treasury and Fed officials poring over their books as the firm expired.42 As a result, no institution was prepared to lend to another, for fear that its borrower too would c...