![]()

PUSHING, PULLING, AND BREAKING

“Because things are the way they are, things will not stay the way they are.”

Bertolt Brecht

![]()

Notes on the Class Struggle

“I can be influenced by what seems to me to be justice and good sense;

but the class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie.”

John Maynard Keynes

The worker who gets a bad back from heavy lifting and the worker who gets a bad back from sitting in the same chair all day do not necessarily identify with each other. The worker who can’t travel because she’s working all the time and the worker who can’t travel because she has no job and therefore no money to travel can feel like they have very different problems.

Where class struggle is not obvious, class itself can seem like a strange concept. Everyone can seem like an individual commodity seller trading on the market, or a citizen with equal rights in a political process. The only way to change anything seems to be making exchange more equal and extending political rights further. The real social relationships at the base of society are invisible, taken for granted, misunderstood, or just unnecessary.

From the point of view of an advertising firm or a politician trying to get a message across, there’s no need to look at these social relationships. Society is chopped up into demographic slices based on political preferences or purchasing power. A sociolinguist studying how speech patterns relate to income might look at society and find six or seven or eight classes.

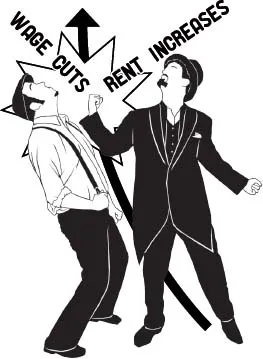

But a situation of zero struggle is impossible under capitalism. Capital has to grow or die. Businesses have to be profitable and competitive. They have to push us to work harder, for less. They have to attack our standard of living. Everything has to be shaped and reshaped to the needs of capital accumulation, or the economy stagnates. Capital is constantly looking for new and better ways to squeeze us.

Our everyday lives are a struggle—to survive, to make work as painless as possible, to keep capital from eating up every day of our lives.

When we start to fight for our own interests, a contrast is quickly visible—a contrast between our needs and the needs of capital accumulation. This contrast is what class and class struggle are all about.

As we struggle to survive, we see that other people around us are in the same position. We work together to fight for ourselves. As our needs come into conflict with the needs of capital accumulation, we come into conflict with the people who benefit from capital accumulation: capitalists. As class struggle develops, deepens, intensifies, it becomes clearer who’s on our side.

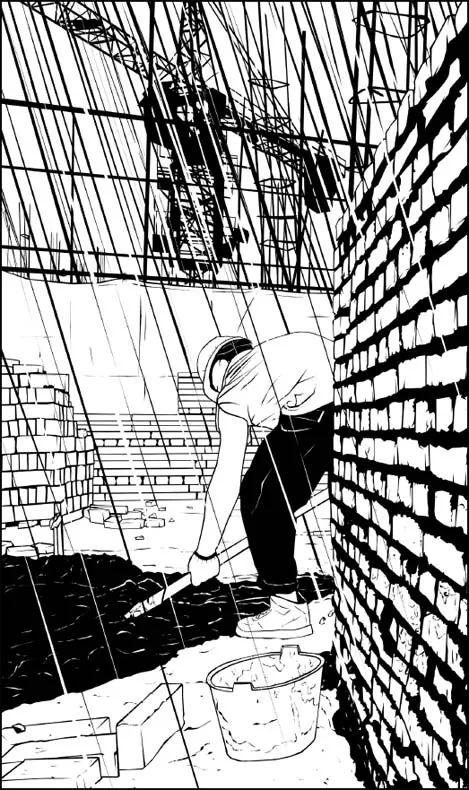

Some of the guys working for a small construction company might have talked to the boss and thought he was a nice guy, but the friendly atmosphere quickly disappears when the boss starts to put pressure on the guys to work faster. When there’s a strike or conflict, the manager, foreman, or supervisor who’s paid only a little more than the rest of the employees is forced to choose a side. Taxi drivers, truck drivers, or nurses who are classified as “independent contractors” go on strike. The police officer who we might have had a friendly conversation with at the bar is called in to evict squatters, to shoot rioters, or to break up the illegal picket lines of striking workers. The underlying class relationship becomes more clear. It becomes less and less of a simplification to see society as divided between those with loaded guns, and those who dig.

Quietly working or apart in our apartments, it’s impossible not to feel alone, weak, and powerless. As we come together and fight for our interests, a different kind of community is formed. Prejudices are weakened or broken down. Class conflict comes out of the basic capitalist social relationships, but when it breaks out, it cuts across and cuts up the already existing communities. The stronger the community of workers in struggle, the more the religious, national, ethnic, neighborhood, and craft communities look thin and archaic.

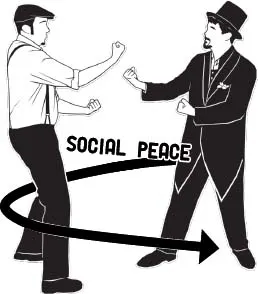

When we’re stronger, more unified, more organized, more militant, we can more effectively fight for our interests and win real concessions. But it’s not a simple matter of making demands, organizing, and then getting concessions. Class war is not like conventional war. Two sides do not meet on the battlefield and gain and lose ground. The interests, weapons, objectives, and edges of a community of workers in struggle are not simply set from the beginning.

A strike can be an expression of working-class power. It can also be a top-down move by a union bureaucracy meant to head off any expression of that power. A squat can be a direct confrontation of our needs and the needs of capital invested in the land. It can also be a marginalized and irrelevant adventure for strange-looking kids. A “defeat” can be demoralizing and destroy a movement, but it can also lead to regrouping, widening, and strengthening of a movement. A “victory” can drive the struggle forward, but it can also mean institutionalization and dissipation of the movement. What counts as a real gain and a loss is not always immediately obvious.

Whenever we start to fight for our interests there is immediate pressure to look at things from the perspective of capital and to make demands that don’t cause any problems.

Sometimes we’ll make demands that are weak, divisive, or self-defeating all on our own—demands for stricter immigration controls or more barriers to entry into a job, demands for more differentiation in the workforce based on education, skill, or experience, demands that link our pay to the profitability of the businesses we work for in various ways. More often, though, community leaders, union bureaucrats, or politicians will make these demands on our behalf. The more we take profitability and the “needs of the economy” as given, the more we are defeated before we begin.

Any government or political system is based on compromises between capitalists in different industries, different politicians, different community leaders, and different sections of the working class. These compromises are based on a set level of exploitation, a set distribution of value and surplus value. Economic crisis and the pressures of competition force the capitalist class to rearrange these compromises and attack our standard of living. Working-class struggles tend to disrupt these compromises by pushing in the opposite direction. Class war keeps coming back.

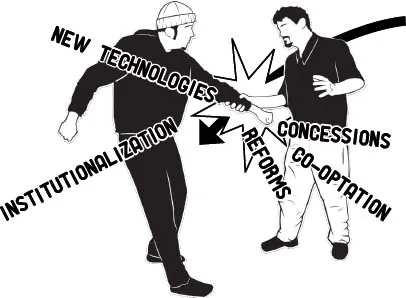

Faced with a serious working-class threat, the capitalists of any country will respond with some mix of reforms and repression, co-optation and marginalization. They don’t much care what we’ve demanded or whether we’ve demanded anything. Their goal is to end the disruption caused by our struggles. The question for them is what reforms will best keep us under control. They need to break up the community we’ve built up during and through the fight or harness it to the needs of capital accumulation. They will give concessions to one part of the movement and repress another part. They’ll legalize one part and criminalize another. They’ll promote some and fire others.

If we’re strong enough and unified enough, we can force reforms that are actually at the expense of profitability. We can force changes that haven’t been done before or that push and pull the system in new and different directions. These kinds of reforms are bitterly fought by the capitalists.

Still capitalism is adaptable. Governments can be replaced. Laws can be changed. Major reforms are possible. Reforms that push capitalism to adapt and progress can become a relatively permanent part of the system. The balance of forces are rearranged, the community of workers in struggle is cut across, and exploitation takes on a different shape. Organizations, groups, attitudes that were previously seen as a threat to the system are neutralized and made into a part of the system. The terrain of class struggle shifts. Gains are turned into defeats. Some of the old communities and prejudices reassert themselves. Some new ones are formed. The community of struggling workers is fragmented. Progress within capitalism is built on the back of class struggles defeated in this way.

The next time we press our needs against the “needs of the economy” the shapes and strategies of a community of workers in struggle will have to adapt as well. We have to critique both the “failures” and the “successes” of previous movements or be quickly defeated.

Capitalism can bend, but it can’t bend into any shape, and it can’t bend as easily in any direction. The more we push and pull, the more clearly we see the shape of capitalist social relationships: what is essential, what isn’t, how things relate to each other. Certain demands and reforms are not easily incorporated or begin to erode immediately. Capitalism pushed in certain directions quickly snaps back. Capitalism is based on class struggle but it is also based on one side always eventually winning.

![]()

Collective Living

“It is a long way from a common laundry

to a socialist dwelling.”

Karel Teige

Looking at the overwhelming isolation of modern suburban housing, of hundreds of individuals and families cooking food, doing laundry, watching TV, staring at computers for hours by themselves, it’s easy to feel nostalgia for a more communal way of living. But modern privacy and separation hasn’t replaced family living—it works on top of it. The same cities where individuals live alone in the suburbs also have people who live with their parents until they have children of their own—or longer—and 3 or 4 generations are living together in the same household. This is real community—real community that tends to impose social conformity, to be conservative and to overlap with strict and restrictive religion. Market isolation and fragmentation and conservative community play off each other. The teenager wants to get out of her parents’ house as fast as possible. The middle-aged man gets married just so he’s not alone. To be a full grown-up means to be alone—or alone with a family. Collective living outside the family is usually looke...