![]()

1

Previously on Red Army Faction

FORTY YEARS AGO, THE WORLD was a very different place.

The division between “Communism” and “The Free West”—détente notwithstanding—marked each and every political conflict, as did the anticolonial revolutions, which had by no means run their course.

Millions of people around the world felt that it was reasonable and worthwhile to risk their lives fighting for liberation from capitalism and imperialism, joining movements with these stated goals. This global upheaval found its epicenter in the Third World, and yet its effects left no nation unchanged. While in the wealthy imperialist countries these revolutionary movements were most evident in the 1960s, there remained pockets of resistance, subcultural remnants, people who persisted in putting their lives on the line, carrying the struggle forward through the 1970s and beyond.

This is the story of one such group, the Red Army Faction (RAF).

West Germany, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), was an anticommunist state set up after World War II to threaten the Soviet bloc, around which imperialism hoped to and succeeded in rebuilding Western Europe’s economy. As part of this process, immediately after the war the capitalist Allies decided to make peace with former Nazis and their supporters, so long as they were willing to play ball with the new “democratic” masters. Throughout the late 1940s, the ‘50s, and the ‘60s, many of the key positions of power in the FRG were occupied by men who had played similarly important roles in Hitler’s Third Reich.

As a substitute for any real denazification, religious and civil leaders simply repeated the mantra that the best way to make sure the crimes of the Nazi period were never repeated was for all Germans to concentrate on living “decent, law-abiding” lives. A message that would often be repeated by parents—not a few of whom had sieg-heiling skeletons in their closets—to their children.

A stifling, authoritarian, and conformist ideology was being imposed from above, a perfect match for the cultural wasteland that had been sterilized in the postwar period, just as it had been “Aryanized” by fascism.

The global wave of revolt that became known as the “New Left” hit the FRG in the 1960s, just as it was reaching the other imperialist countries. Students in West Berlin began questioning not only the economic system, but the very nature of society itself. The structure of the family, the factory, and the school system were all challenged as these young rebels mixed the style of the hippie counterculture with ideas drawn from the Frankfurt School’s brand of Marxism.

In 1966 and ‘67, a recession that had hit the entire capitalist world pushed unemployment in the FRG to over a million for the first time in the postwar era. In a move to preempt dissent, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) was brought into a so-called “Grand Coalition” government alongside the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its more rabid Bavarian counterpart, the Christian Social Union (CSU). With the putative “left” working hand-in-hand with the right to manage the crisis, it appeared that any real change could only come about outside of government channels. Disenchantment struck West Germany’s youth in the factories and on the street, as younger workers were increasingly marginalized by the new corporatist compact—but most especially in the universities, which had been bastions of right-wing power for over a hundred years.1 The Außerparlamentarische Opposition (APO), or Extra-Parliamentary Opposition, was born.

Communes and housing collectives began to spring up. Women challenged the male leadership and orientation within the student movement and the APO, setting up daycares, women’s caucuses, women’s centers, and women’s communes. The broader counterculture, rockers, artists, and members of the drug scene all rallied to the emerging political insurgency. Political protests encompassed traditional demonstrations, as well as sit-ins, teach-ins, and “happenings.”

This was all the more striking given the conservative cultural and political situation in West Germany at the time. In retrospect, it may not be difficult to see that the student revolt was one part of a complex and often contradictory process of social transformation, through which capitalism was not only being challenged, but also renewed, new classes rising as old classes updated their worldview. At the time, however, the gulf that separated the student protesters from the surrounding society could seem well-nigh unbridgeable.

The APO was opposed by a rabidly right-wing gutter press and gratuitous violence, which would be exemplified for many by the killing of Benno Ohnesorg, a young student shot dead by police while attending his first demonstration in West Berlin, on June 2, 1967.2 In this context, the APO was forced to develop a capacity for street militancy, as ongoing attacks on the movement combined with the specter of Germany’s recent past to imbue it with a sense of “do or die” urgency—an attitude that was sadly vindicated, as Socialist German Students Federation (Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund, or SDS) leader Rudi Dutschke, the target of a hate campaign in the popular Springer Press, barely survived being shot three times by a would-be assassin in 1968. (He would in fact die as a consequence of his injuries eleven years later.)

In radical circles it was a commonplace that the Federal Republic was simply the Third Reich in new clothing, and this view—made all the more credible by the violence directed at the New Left—had consequences as to the place that repression, violence, and resistance would all play in activist strategies. As Irmgard Möller would recall, over thirty years later:

Repression had not brought people together, but it had sharpened the perspective of those affected. Who is it that one confronts? How can one protect oneself? Above all, it became clear that people could only defend themselves if they acted together! Then, the overview of the entire justice system, the repressive system—what would they go after? What grinder would they put us through? I’m not saying that persecution automatically gives rise to something good. But at the time, it was important that anyone who had ever set foot on the street—against the state of emergency legislation, protesting the Vietnam War, the junta in Greece, there was an endless stream of demonstrations and demonstrations—felt threatened. All of this was criminalized.3

It was within this context, and inspired by the liberation struggles occurring in the Third World, that militants began experimenting with a new form of political intervention: the urban guerilla.4

Initially, this armed development manifested itself in two broad tendencies. A constellation of groups based in the communes and the counterculture, often described as anarchist, carried out a number of firebombings, robberies, and attacks on police. They operated under names such as the Tupamaros Munich and West Berlin, the Raging Panther Aunties, the Central Committee of the Roaming Hash Rebels, the West Berlin Yippees, and the Blues—by 1972, elements from all these had coalesced into the 2nd of June Movement (2JM), the group taking its name from the date of Ohnesorg’s murder in 1967. This first tendency was marked by a more populist approach and paid particular attention to the question of class within the FRG.

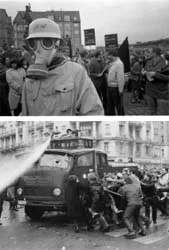

Demonstrations following the murder of Benno Ohnesorg in 1967 (top) and attempted assassination of Rudi Dutschke in 1968 (bottom).

The second guerilla tendency to emerge was more clearly a product of the student movement, for whom capitalism had been discredited, not so much by internal class oppression but by its past and present complicity in military aggression and genocide around the world.5 This second tendency overlapped significantly with the first, with several individuals crossing back and forth, but it would ultimately develop along a separate path.

Those who followed this path constitute the subject of our study, the guerilla organization they established being the Red Army Faction.

A STRATEGY AGAINST IMPERIALISM

The Red Army Faction first announced itself in 1970, when a small group broke a young man out of jail.

Andreas Baader was serving a three-year sentence for having set fire to two department stores to protest the war in Vietnam. One of his rescuers, Gudrun Ensslin, had also participated in this political arson, and, as such, was living underground at the time. Another rescuer, Ulrike Meinhof, was a well-known left-wing social critic, a journalist who had been putting the finishing touches on a docudrama about girls in reform school. Significantly older than the other guerillas, within the FRG she was in fact the best-known left-wing female intellectual of her generation; due to her role in Baader’s escape she had no choice but to go underground.

The RAF made international headlines with this jailbreak, during which an elderly librarian was shot and seriously injured, and the operation was hotly debated on the left. All the more so when one year later at the annual May Day demonstration in West Berlin, supporters handed out copies of the group’s foundational manifesto, The Urban Guerilla Concept, a document that not only made the case for armed struggle in the metropole, but also established the RAF’s reputation as a group that took political theory seriously.

In this and subsequent texts, the RAF would develop a distinctive analysis of capitalism and the possibilities of resistance “in the belly of the beast,” addressing the difficult fact (as formulated by former RAF member Knut Folkerts), that “All revolutionary initiatives in [Germany] suffer—if they do not wish to resolve the question opportunistically—from the contradiction between the reality presented by this population and the need to find a base here.”6

Grappling with this, the RAF would combine insights from the Frankfurt School and other European Marxist intellectuals with the anti-imperialism of their day, arguing that the First World working classes suffered a unique form of psychological/cultural oppression, the “twenty-four-hour-workday,” saturated with “consumer terror.” That oppression notwithstanding, according to their subjectivist anti-imperialism, material issues in the metropole no longer qualified as the primary contradiction; the battlefield had shifted to the Third World, and the national liberation movements now constituted the global vanguard. While it was not exempt from contradictions and class oppression, for various reasons (social democracy, consumerism, and integration into the state, to name a few) the metropole, imperialism’s “safe hinterland,” had become a place where people could only be mobilized for revolution through a personal breakthrough, for instance, the realization that life under capitalism is alienating, that commodities are no replacement for communities, or that living off the blood of others is unacceptable.7

While aspects of this analysis could be found in The Urban Guerilla Concept, a countervailing focus on poverty in West Germany was evident in Serve the People: Class Struggle and the Guerilla, released in May 1972.8 These ideas would find their ultimate synthesis in The Black September Action in Munich: Regarding the Strategy for Anti-Imperialist Struggle,...