![]()

Radical Interventions in the Professional Game

A Stage for Protests

Professional football has been used as a stage for political protests in various ways. To name but a few examples: in the 1970s, streakers regularly disrupted Premier Division football games in England; during the West Germany vs. Chile match at the 1974 Men’s World Cup, activists stormed the pitch and waved flags with the slogan Chile sí, Junta no in protest against the military dictatorship; at the 1982 Men’s World Cup game between Poland and the Soviet Union, banners reading Solidarność were unrolled in support of the Polish trade union movement; in 2006, a protester wrapped in a Palestinian flag ran onto the field during a Glasgow Rangers vs. Maccabi Haifa match, trying to chain himself to a goalpost; in 2009, activists in Sweden hoisted a banner at Gothenburg’s Ullevi Stadium demanding the release of the Eritrean-Swedish journalist Dawit Isaak, imprisoned in Eritrea since 2001. Sometimes, the political messages at football games can be government-sponsored. In Iranian stadiums, teams have been welcomed with slogans like Down with the USA! or Israel must be destroyed!. That football supporters also have a sense of humor was proven by Scotland’s infamous supporter community, the Tartan Army: when Scotland played the Soviet Union at the 1982 Men’s World Cup, a banner proclaimed Alcoholism v Communism.

Football stadiums have also been sites of coded political protest. During the Third Reich, the hostile reception of German sides at Viennese football grounds were hardly concealed protests against the Nazis’ annexation of the country. Under Franco’s regime in Spain, forbidden songs were intoned in Catalonian and Basque stadiums.

Football victories have served as catalysts for public rebellion. When the Iranian men’s team beat Australia for the final spot at the 1998 World Cup tournament, thousands of Iranian women stormed the stadium, defying clerical orders that ban them from stadiums when men are present. During the team’s qualification campaign for the 2002 World Cup, banks and public offi ces were attacked and anti-government slogans shouted. When Iran lost their final game to underdog Bahrain, rumors abounded that the loss had been ordered by the regime in fear of further disturbances in the case of victory.

In such a political climate, the tiniest gestures can become acts of political resistance, for example when staff members of Esteghlal Tehran allowed one of their men’s youth teams to meet the women’s side in January 2009—as a result, three club officials were suspended.

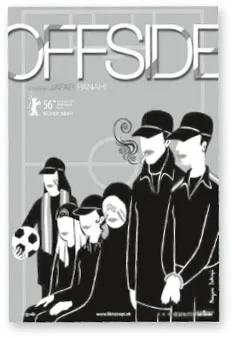

Iranian Women Barred From Soccer Games

A Review of the Movie Offside by Jafar Panahi AlterNet, April 26, 2007

Chuleenan Svetvilas

What happens when six Iranian young women disguise themselves as men so they can watch a World Cup qualifying match in Tehran? This is the situation in which director Jafar Panahi places his talented actors (all nonprofessionals) who play their fictional roles in the very real setting of a soccer stadium in Iran, where the national team faces Bahrain.

Women are not allowed in sports stadiums in Iran. So when Panahi went to get permission to make his film, he told the authorities that it was about boys who go to a soccer game. He got approval and promptly made Offside, a humorous and engaging film that defies easy categorization. It’s not quite a sports movie—we only get a few distant glimpses of the soccer match—and it’s not a purely fictional film. But one thing is certain: It is a film worth seeing.

Panahi got the idea for the film several years ago when his daughter wanted to accompany him to a soccer stadium. He didn’t think she would be allowed in, but he decided to take her anyway. She was indeed turned away, but to his amazement, found a way in and joined him in the stands.

Winner of the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, Offside captures the plight of women soccer fans who try—often unsuccessfully—to bluff their way into the stadium.

In an early scene, we see a young woman trying to pass as a man on a stadium-bound bus full of men. One passenger points her out to his friend who remarks that women know how to get into the stadium. Instead of reporting her to the authorities, they let her continue her quest to get in. Panahi makes it clear at the outset that people do find ways to get around the rules, and not everyone agrees with enforcing them.

Besides providing lively, character-driven entertainment, the film comments on the political and social contradictions in Iranian society, where, for example, custom prevents women from attending soccer games (to shield them from profanity) but allows them access to movie theaters.

Much of the film takes place in the holding area on the upper level of the stadium where women are forced to stay until the vice squad picks them up and takes them away. The women can hear the crowd but can’t see anything, so they plead with the soldiers to let them inside the stadium, saying that they can blend in with the crowd. One woman points out that Japanese women were in the stadium when Japan played Iran. “Well, they couldn’t understand the swear words,” says one soldier. “So my problem is that I was born in Iran?” she retorts.

The camera often takes a vérité documentary approach, blurring the line between fact and fiction. Some of the soldiers are not just playing a role; they are real soldiers serving in the Iranian army. And Panahi’s direction is so self-assured and the acting so natural that you forget that you are watching actors. He captures the fervor of soccer fans—male and female—and their intense desire for their country to qualify for the World Cup.

The script, written by Panahi and Shadmehr Rastin, is filled with unexpected humor, particularly from the women who have the best lines. Upon seeing a tomboy smoking a cigarette, one of the soldiers asks if she’s a girl or a boy. “Which do you prefer?” she replies.

Another laugh-out-loud scene occurs when one of the women must use the bathroom, which is, of course, for men only, and we see how one soldier struggles with the task of taking her there and “protecting” her from the graffiti on the walls. Here, Panahi shows the perspective of the soldiers, who are not comfortable with confining the women but also don’t want to get in trouble with their superiors and risk having more time added to their mandatory military service.

According to press notes, none of Panahi’s films have been released in Iran; however, Offside did have at least one screening in Tehran at the Fajr International Film Festival last year.

Panahi’s previous films have been described as neo-realist and dealt with poverty-stricken men and the struggle of women in Tehran, apparently subjects the Iranian government doesn’t wants its people to be reminded of. Panahi says that he makes his films for Iranians, but so far, his main audience has been people outside of Iran who have seen his work at film festivals and in art house theaters.

Offside has been a darling of the film festival circuit, and deservedly so. It is now making the art house cinema-rounds in the U.S.

In Libya as well, football has served as a site for coded political protest, mainly in the fierce opposition to Alahly Tripoli, a club that enjoys the backing of Muamar El-Gadaffi and his sons. Clashes during a derby against city rival Al-Ittihad in 1996 reportedly left fifty people dead.74

In Saudi Arabia, football was the background to a politically charged incident in 2009, when, during a live TV program, Prince Sultan bin Fahd, head of the FA, lashed out at reporters who had dared criticize the performance of the Saudi Arabian team. When the prince suggested that they “had not been raised well,” a deep insult in Saudi culture, the former national team player Faisal Abu Thnain objected—it was the first time that a Saudi citizen questioned a member of the royal family in public.

On rare occasions, football associations themselves have played a role in political resistance. The Football Association of Indonesia (Persatuan Sepak bola Seluruh Indonesia, PSSI), founded in 1930, was active in the anti-colonial struggle against the Dutch. Similarly, the South African Soccer Federation (SASF), founded in 1951 as an integrated opponent to the all-white Football Association of South Africa (FASA), took on an active role in the anti-apartheid struggle. In 1991, at the eve of apartheid’s defeat, the SASF merged with other South African football organizations to form today’s South African Football Association (SAFA).

On a humorous note, football was used to express a community’s overall frustration with the political system in the British town of Hartlepool in 2002, when the local team’s mascot, a monkey, was elected mayor.

Social Justice Campaigns

A number of social justice campaigns have touched on soccer, mainly connected to labor rights and anti-sweatshop activism. The best known of these might be the FoulBall Campaign, launched by labor rights organizations in 1996 after a Life magazine article had addressed the production of soccer balls in Pakistan’s Sialkot region, where 75 percent of the world’s hand-stitched soccer balls are made. The article revealed that twelve-year-old kids received sixty cents for stitching balls that Nike, Adidas, Umbro, and other companies sold for up to fifty dollars in the United States. The maximum number of balls that these kids were able to finish in a day was two.

The FoulBall Campaign made the sports company giants react, but mainly on a public relations level. Labels like Guarantee: Manufactured Without Child Labor, Certified: No Child or Slave Labor Used on this Ball, and Adult Sewn Product appeared. Puma introduced a FairTrade ball in 2008.

FIFA has supported the campaign by making star players’ hold hands with children while entering the field. Meanwhile, little has changed on the ground. The following is the summary of a 2010 report by the International Labor Rights Forum (ILRF):

More than half of the 218 surveyed workers in Pakistan reported that they did not make the legal minimum wage per month. In one Pakistani manufacturer, ILRF researchers found that all interviewed stitching center or home based workers were temporarily employed resulting [in] workers not having access to healthcare or social security. In the same Pakistani manufacturer’s supply chain, female home-based workers faced discrimination based on their gender. They were paid the least and faced the possibility of losing their jobs permanently due to pregnancy. In one Chinese factory, workers were found to work up to 21 hours a day during high seasons and without one day off in an entire month. Indian stitching centers were described as “pathetic.” Proper drinking water or medical care facilities, and even toilets were often absent. Child labor was identified by workers producing for three different factories in Pakistan.75

Personalities

Very few prominent football personalities have used the platforms provided by their popularity for sound political intervention. Arguably, people with strong political principles often do not make it to the top-level because they cannot deal with the authoritarian and corporate structures, or because they are weeded out as troublesome players. Barney Ronay wrote in a 2007 Guardian article, “At the top level at least, footballing socialists are an almost extinct breed.” He quotes former Scotland international Gordon McQueen, who states that “I’d say 99 percent [of all footballers] are totally uninterested in politics.”76

Most players who dabble in political affairs lend support to conservative parties, like England’s Kevin Keegan, or they run for office based on their fame: Pelé has acted as the Minister of Sports for the Brazilian government, and former AC Milan striker George Weah ran as a candidate in Liberia’s presidential elections of 2005. Others, like Michel Platini, the current UEFA president, have worked their way up in the ranks of international football bureaucracy.

There are even footballers with well-established links to loyalist paramilitaries, like Scotland’s Andy Goram, and self-professed fascists, like Italy’s Paolo di Canio, who sports a Duce tattoo and enjoyed greeting Lazio Roma’s right-wing fan groups with the fascist salute. The fact that the Italian keeper Gianluigi Buffon has sported a fascist slogan on a T-shirt (Boia chi molla—roughly, “Death to Deserters”) and that he chose the unfortunate number 88 at Parma (a code for Heil Hitler! in white supremacist circles) was probably based on ignorance rather than neo-Nazi conviction, but still leaves a bad aftertaste. Speaking of ignorance, it is hard to beat the answer of Berti Vogts, captain of the German team at the 1978 Men’s World Cup in Argentina, to a journalist who inquired if Vogts was worried about playing in a country full of torture chambers: “Not at all,” he said, “I don’t think that anything will happen to us.”77 In comparison, it is refreshing to see Thierry Henry in a Che Guevara shirt or Juan Verón with a Che tattoo—even if these choices might be based on political ignorance as well. Verón has stated that his Che tattoo was not a political statement but a way to honor an “Argentinean hero.”78 So much for Che’s internationalism!

There are some more encouraging examples, though.

Matthias Sindelar was a legendary Austrian player in the 1930s. Due to his frailness he was known as der Papierane (Austrian for “made of paper”), but he made up for physical weakness with exquisite technical skills. In 1938, after the Nazi annexation of Austria, he refused to play in the new “pan-Germanic” team and ran a café in Vienna instead. He was found dead in an apartment in January 1939, together with an Italian woman whom he had met a few days earlier. The official cause of death was carbon monoxide poisoning, but the exact circumstances were never clarified. The police reports of the case went mysteriously missing.

Gusztáv Sebes was the manager of the Hungarian side that dominated world football in the early 1950s before sensationally losing to Germany in the 1954 Men’s World Cup final. The Hungarians staged their probably biggest upset whe...