![]()

1

North American Freedom Struggles

THE THREE DECADES FOLLOWING WORLD WAR II, ROUGHLY 1945 TO 1975, WITNESSED an array of upheavals around the world that continue to influence the political, economic, social, and cultural landscape. Perhaps the most important development internationally was the success of anticolonialism. With European colonial powers stretched thin by a costly world war, radical and revolutionary movements throughout the Third World of Africa, Asia, and Latin America began achieving independence or emerging triumphant against Western-supported dictators in their own countries. In most cases, these movements attempted to replace the corrupt regime with some form of socialism. Most of these Third World liberation movements struggled for independence from the colonial regimes or the overturning of neocolonial regimes that had controlled their countries for decades or generations. The list of victories was impressive and seemed permanently expanding: beginning with China in 1948, there were successful revolutions or triumphs by popular movements in Ghana (1957), Guinea (1958), Cuba (1959), Cameroon, Togo, Senegal and Mali (1960), Algeria (1962), Chile (1970), Guinea Bissau (1974), Angola and Mozambique (1975), Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos (1975), Grenada (1979), Nicaragua and Iran (1979), Zimbabwe (1980), Namibia (1991), South Africa (1994), and dozens of others. Such sweeping and at least initially radical change defined the Third World as a political project in its own right, separate from either the capitalist First World or the bureaucratic communism of the Second World—although some national liberation movements did align with the Soviet Union or China and received much-needed material aid from the “socialist camp.” These movements united revolutionary nationalism with some form of socialism and an eclectic range of tactics to achieve independence. While recent history has shown capitalism’s ability to colonize without formal armies, as well as the problem of leftist authoritarian rule, the sweeping tide of revolution seemed to leave no country unaffected in the two-decade period known as “the Sixties.”

Soledad Brothers George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Clutchette in a police van, circa 1971.

BLACK LIBERATION AND SETTLER COLONIALISM

Within the United States, the Third World socialist project was most forcefully articulated by the Black liberation struggle. Through the internationalist politics of many leaders and rank-and-file activists, Black liberationists identified their cause with anticolonial resistance overseas. More than affinity, however, this unity was born of a similar designated status. As the Sixties wore on, many radicals began to speak of peoples of color in the United States as “internal colonies,” captive nations within a “settler colonial” empire. Rather than a colonial government serving a faraway power, settler colonies are those countries—the United States, Israel, Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand—established through the settlement of foreign populations as dominant classes and the imposition of institutions and structures upon a displaced and marginalized Indigenous population. Settler colonialism in the Americas is based on both the slaughter and containment of the Indigenous population, as well as the subjugation and control of African slaves and their descendants.

Viewing the situation of Black people and other peoples of color as one of internal colonialism was a natural complement to the militant politics already developing within the movement. This analysis joined race and class as constituent elements of colonial rule: the nations internal to the United States were the most oppressed populations, where race served as a marker of class distinction. The goal was to liberate the captive nations—and, as Black Liberation Army soldier Mtayari Shabaka Sundiata once put it, “How can we talk about a nation and not talk about an army?”

While the armed actions of the 1970s marked a different phase of the Black liberation movement, this shift was not as unprecedented as some have suggested. The civil rights movement was never as nonviolent as it has been traditionally depicted; sections of it were always armed (most famously the Deacons for Defense), and even the unarmed aspects were constantly seeking to raise the stakes of resistance to white supremacy. Groups like the Revolutionary Action Movement worked behind the scenes in the early to mid-1960s to develop both Black nationalist consciousness and the capacity for armed resistance. As civil rights activists became more effective and with the quick growth of a selfconsciously Black Power movement, the struggle for Black liberation clashed with an entrenched white supremacist power structure and increasingly repressive state.

The Black Panther Party (BPP) was the best-known of the revolutionary nationalist formations in the late 1960s. Born in Oakland in 1966, the Panthers had grown to a nationwide organization in just two years. It was, as former New York Panther Jamal Joseph has said, a Black organization rooted in class struggle. Panther chapters in cities across the country built a series of community programs; the best-known entailed community defense, whereby Party members would observe police officers making arrests in an attempt to thwart brutality or stop the arrest altogether. The Panthers also engaged in free community healthcare and breakfast for children programs, among other “survival pending revolution” operations. With the full weight of state repression against them, the Panthers soon began racking up political prisoners on charges big and small. And the repression wasn’t just based on imprisonment; part of the FBI’s campaign against the Panthers, as codified in its Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO), entailed spreading distrust within the group and between the Panthers and other radical groups. Sometimes these FBI-fostered hostilities degenerated into violence; for instance, the shooting deaths of Panther activists John Huggins and Bunchy Carter in early 1969, ostensibly by members of a rival organization, were in fact provoked by the police. Police had already killed Bobby Hutton, one of the first to join the Panthers, on April 6, 1968, and a dozen other Panthers were felled by police by 1970. In addition to the murder of Panther activists, both leaders and rank-and-file activists found themselves facing a variety of charges for acts real and imagined.

Such repression bred a climate of fear and distrust internally, as well as a push toward clandestine armed struggle. Black communities had been increasingly in open revolt against the state, especially the police; there were hundreds of rebellions in cities across the country between 1964 and 1968 (dubbed “urban riots”). In that climate, several police officers were killed, and the government increasingly looked to blame Black Panther activists for any attack against police or, for that matter, white people in general. LA Black Panther Romaine “Chip” Fitzgerald, for instance, remains in prison from a 1969 shootout with police. This climate made it easy for the state to frame Black radicals. To name just a few cases: Panther leaders Dhoruba Bin-Wahad in New York and Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt in California both served time in prison (nineteen and twenty-seven years, respectively) for attacks of which the state knew they were innocent. Mondo we Langa (formerly David Rice) and Ed Poindexter in Nebraska continue to serve time on trumped-up charges, as do Marshall Eddie Conway in Maryland and Herman Bell and Jalil Muntaqim of the New York 3. (Their codefendant, Albert “Nuh” Washington, died of cancer in prison in April 2000 after almost thirty years inside.)

Two instances of repression particularly stand out in the formation of a Black underground: in a predawn raid on December 4, 1969, Chicago police murdered Mark Clark and Fred Hampton, the twenty-one-year-old leader of that city’s Panther chapter. Police fired almost a hundred bullets into the apartment, unprovoked, seriously wounding Hampton as he slept (a police informant had drugged him to ensure his slumber) and then finishing him off execution-style with two bullets to the head, fired at point-blank range. Four days later, Los Angeles police attempted a similar predawn raid on the Panther office there, though the chapter was prepared and survived the assault. The message was unmistakable: the government was bent on destroying the Black Panther Party by any means necessary.

The other key incident at this time was the April 1969 indictment of twenty-one Black Panthers from the BPP’s New York chapter for a host of fabricated, violent conspiracies. Although all were acquitted by the jury in less than an hour, the trial lasted two years, during which time most of the accused remained in prison, as bail had been set at $100,000 each. Even without securing convictions, the government had managed to remove most of the leadership and key activists of the New York chapter. And during those two years, internal divisions within the Panthers had become unbridgeable, as BPP cofounder Huey Newton expelled many members of the New York 21, as they were collectively known, for questioning his leadership. Many of the defendants from that case either went into exile with the international chapter of the Panthers or they went underground to help form the Black Liberation Army (BLA).

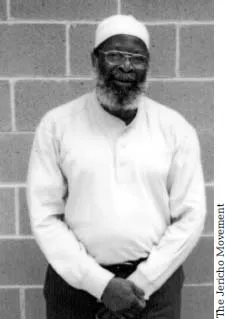

The BLA emerged in a climate of heightened police repression, not only against Black liberation activists, but against the Black community at large. Police shootings and killings of unarmed civilians, including children, had become a regular feature of urban life by the late 1960s. Viewing the police as an occupying army, the BLA crafted a response of guerrilla warfare. While the idea, and perhaps even the infrastructure, for the BLA had long been in the making, the organization announced its presence through armed attacks against police as retaliation, not against individual officers but against police violence in general. In 1971 alone, the FBI claimed that the BLA carried out more than a dozen attacks on officers in California, Georgia, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. The BLA claimed responsibility for several of these in communiqués sent to the media. Between 1971 and 1981, at least eight alleged BLA members were killed in shootouts with police, and more than two dozen were arrested. In many cases, the shooting was initiated by police, and the alleged BLA members were then falsely accused of wounding or killing their attackers. Most notorious were the murder charges brought against Assata Shakur and Sundiata Acoli following their arrests on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1973 (in an incident where BLA member Zayd Shakur and a police officer were killed). Despite evidence showing their innocence, they were convicted in separate trials and sentenced to life. In addition to engaging the police in combat, the BLA also had a campaign against drug dealers in the ghettos, whom they saw as sapping the strength and vitality of Black communities; BLA prisoner Teddy Jah Heath, who died in prison in 2001, served twenty-eight years for the kidnapping of a drug dealer in which no one was hurt.

Lacking wealthy benefactors or steady access to resources, BLA cells often relied on bank robberies to secure funds (a tactic revolutionaries call “expropriations,” for it involves taking money that capitalist institutions have secured through other people’s labor and using it ostensibly to further liberatory ends). In a phenomenon other revolutionary groups would also experience, many BLA soldiers were captured engaging in these high-risk actions.

As members of a clandestine army fighting to free a colonized people, most captured BLA combatants have defined themselves as prisoners of war, not just political prisoners. Several attempted to escape from prison, often with the help of units on the outside—sometimes successfully, at least for short periods of time. Among those still incarcerated for alleged BLA activities (and not mentioned above) are Russell “Maroon” Shoatz, Kojo Sababu, Joe-Joe Bowen, Bashir Hameed, and Abdul Majid. Meanwhile, after their release, former BLA soldiers and POW’s, such as Ashanti Alston and Safiya Bukhari among many others, became stalwart organizers for the freedom of remaining prisoners.

By 1975, there was a lull in BLA activity, as many participants were on trial or in prison. At this time, the group’s attention turned toward consolidating its political ideology through small-scale newsletters, a study manual, and communiqués. On the outside, however, others began rebuilding the BLA’s capacity to carry out even grander actions than had been undertaken to date.

In November 1979, the BLA made an auspicious public reentry, helping Assata Shakur break out of prison in New Jersey; it was a daring escape, made more impressive by the fact that it succeeded with no injuries or fatalities. Shakur ultimately went into exile in Cuba, though the state continues to pursue her capture; in 2013, the FBI made Shakur the first woman on the “most wanted terrorist list” and the state of New Jersey offered $2 million bounty for her capture. Besides Shakur, ex-Panther Nehanda Abiodun remains in exile there, as does Puerto Rican independentista William Morales. News reports estimate that Cuba is home to ninety U.S. fugitives, although it is unclear how many of them fled political persecution, nor is Cuba the only place housing U.S. exiles. Former Panthers Pete and Charlotte O’Neal are exiled in Tanzania, and Don Cox lived in France for more than three decades until his 2011 death.

Units of the BLA continued. Two years after Shakur’s escape, in October 1981, several people attempted to rob a Brink’s armored car in Nyack, New York, about thirty miles north of New York City. The expropriation would have netted $1.6 million which, according to a communiqué issued two weeks later under the name Revolutionary Armed Task Force of the BLA, was to have helped fund continued clandestine endeavors and other Black community programs. But the action went awry: a shootout at the Brink’s truck left a security guard dead, and two police officers were killed at a roadblock in an exchange of gunfire a few miles away, as the radicals attempted to flee. Four militants were captured at the scene, including BLA member Sam Brown and three white allies—Kathy Boudin, David Gilbert, and Judy Clark. (Boudin and Gilbert were former members of the Weather Underground and had been living clandestinely for some time; Clark was a leader of the aboveground May 19th Communist Organization; the three were not at the scene of the robbery itself but were arrested at the police roadblock.) A shootout in Queens, New York, two days later left BLA soldier Mtayari Shabaka Sundiata dead and Sekou Odinga in police custody. Police tortured Odinga, burning him with cigarettes, removing his toenails, and rupturing his pancreas during long beatings that left him hospitalized for six months.

In the weeks that followed, an FBI dragnet created a climate of hysteria, sweeping up many other activists, some of whom had nothing to do with the Brink’s incident (and several of whom were ultimately acquitted of all charges). All told, more than a dozen people were arrested leading to multiple trials, at both the state and federal levels, emanating from the Brink’s robbery and the escape of Assata Shakur. Additionally, several above-ground supporters and friends, both Black and white, served time for refusing to testify before grand juries investigating these matters. While many from these assorted trials have since been released, several remain in prison with what, for most of them, amount to life sentences. Clark, Gilbert, and BLA member Kuwasi Balagoon—a veteran of the NY 21 case—were convicted on state felony murder charges in 1983 and sentenced to seventy-five years to life. In another state trial, BLA member Sekou Odinga was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to twenty-five years to life for returning fire against the cops shooting at him prior to his arrest.

Sekou Odinga

In a move that would be repeated in later cases brought against left-wing radicals, federal prosecutors in the Brink’s case used the RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) Act, originally intended for prosecuting the Mafia, to try those they claimed were involved in illegal underground activity. (RICO allows guilt-by-association “conspiracies” to be prosecuted as criminal enterprises). In the 1983 federal trial, Odinga and white anti-imperialist Silvia Baraldini (another May 19th Communist Organization leader) were found guilty of racketeering and conspiracy in connection with an attempted bank expropriation and Assata Shakur’s escape, each receiving a forty-year sentence. Three codefendants facing robbery-murder charges, former Panthers Chui Ferguson and Jamal Joseph and Republic of New Afrika activist Bilal Sunni-Ali, were acquitted of the RICO charges, although Ferguson and Joseph were convicted of accessory charges and received twelve-year sentences. Balagoon and Odinga had attempted to be tried together to collectively mount a POW defense, but they were tried separately (Balagoon by New York State, Odinga by the federal government). Still, both invoked international law in claiming the right to resist unjust rule by force.

Balagoon died of AIDS in prison on December 13, 1986, and Odinga remains incarcerated. Brown was convicted in 1984. (Brown and Clark are not considered political prisoners: Brown was tortured after his arrest and denied medical care until he cooperated with authorities, yet he still received a life sentence, which he serves under protective custody for being a government witness. In the late 1980s, Clark asked to be removed from political prisoner lists.) Kathy Boudin, who pleaded guilty in 1984 to felony murder and robbery, was sentenced to twenty years to life; she was granted parole and released from prison in 2003. Marilyn Buck and Mutulu Shakur were convicted of racketeering and conspiracy in a federal trial in 1988; Buck received fifty years (on top of twenty years for an earlier conviction), Shakur sixty years.

A later case that the FBI falsely dubbed “Son of Brink’s” and a “successor” to the BLA involved an attack on another group of Black revolutionary nationalists: In October 1984, eight members of the aboveground Sunrise Collective—Lateefah Carter, Coltrane Chimurenga, Omowale Clay, Yvette Kelley, Colette Pean, Viola Plummer, Robert Taylor, and Roger Wareham—were arrested in a set of massive, military-style police raids around New York City. They were charged with conspiracy to rob banks and break out Balagoon and Odinga from prison. Using a new “preventive detention” law pushed through Congress by then-President Reagan supposedly to combat the Mafia, prosecutors led by U.S. attorney Rudolph Giuliani convinced a judge to deny bail to the activists—none of whom had any criminal record—as “dangers to the community” and they were all held for several months. The case became known as the New York Eight+ (a ninth, Latino activist José Ríos, was charged later), and it sparked major headlines, mass organizing, and a packed trial. Despite extensive video and audio surveillance and testimony by an informant in the group, in August 1985 the jury acquitted all defendants of the major charges. They were convicted only of minor charges—seven of possession of illegal weapons and one of possession of false IDs; Ríos was acquitted on all counts. In interviews afterward, jurors condemned the FBI surveillance and the prosecutors’ “guilt by association” tactics. One defendant (Pean) received three months’ jail time; the others got probation and community service. (These activists later became the core of the December 12th Movement, which has done much work internationally and at the United Nations to highlight the human rights violations against Black political prisoners and the demand for reparations for Black people.) The New York Eight+ case also led to an investigative grand jury that subpoenaed many Black community members and jailed several who refused to cooperate for months.

Several of those tried for alle...