![]()

PART ONE

Indigenous Childhood; Colonial World

![]()

1. Digging Where We Stand

I must start where I stand. As children, we used to be told that if you dug a really deep hole, you’d come out in Australia. I think in some ways this is very true. If

any of us dig deep enough where we stand, we will find ourselves connected to all other parts of the world.

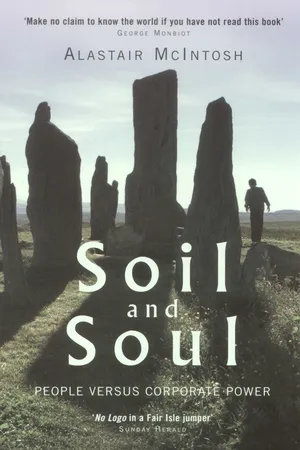

I grew up just 10 miles from the famous Calanais (or Callanish) standing stones. We lived by the village of Leurbost, on the east side of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. The island lies

some 50 miles north-west of the Scottish mainland, out in the Atlantic Ocean.

Our first house, before we moved closer to the village, was a little croft cottage called Druim Dubh. There was no mains water supply. It had a well, from which our tap spluttered a dark,

peaty flow, like real ale, for washing with, and a huge wooden water butt in which we collected drinking water from the roof. Whenever it rained, which was often, we’d hear a trickle running

down the drainpipe and into this tar-caulked barrel. Every morning Dad would scoop out the day’s fresh supply with what we called the ‘water bucket’ and bring it into the

kitchen.

Sometimes, when outside, I would climb up on the wheelbarrow, edge the lid sideways and peer down into the inky depths of the butt. As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I’d look for water

beetles. These had silky wings beneath an armoured outer shell. Because the butt’s lid did not fit tightly, they would fly in and out at night. What made them visible, black against black

though they were, was that each carried its own tiny aqualung. Each had a minute bubble of bright air held tight by surface tension in special hairs at the end of its tapered body. This shone with

a most brilliant translucence. It shone with that vibrant life that only oxygen can give, trapped and fighting for freedom. For me, then aged four, our water butt meant more than just a drink. It

was a magical place. To shift that lid and gaze upon the awesome depths was to see a chest of zooming dancing jewels.

In Gaelic, Druim Dubh means ‘the black ridge’. In recent years a fallen stone circle has been uncovered by peat digging just a stone’s throw from our old front door. It

is out by the rubbish dump on the circular rocky hillock where my younger sister, Isobel, and I used to play. We never knew about the prehistoric stones then. If we had,

we’d have thought of them nonchalantly as ‘just something from the old days’.

To us children in the early 1960s there was nothing exceptional about even the big standing stones over at Calanais. Yes, they were five thousand years old. That meant they had been erected at

around the date attributed to events in the earliest parts of the Old Testament. And yes, they were laid out in the shape of a Celtic cross on a site more spectacular by far than Stonehenge. But

otherwise they were unexciting. The Stones were just a place to get cold or eaten by midges when we showed visitors from the mainland around the island. We certainly had no sense of veneration

towards them. Indeed, the nineteenth-century people of Calanais had taken what seemed a sensibly prosaic attitude. They had used the Stones, or so it has been said, as public conveniences.

Accordingly, they were not greatly pleased when the owner of all Lewis, Lady Jane Matheson, decreed that the site was to be cleaned up and treated with respect of a rather different kind.

In fact, our attitude to the Stones differed little from our attitude to the environment in general. We were often cavalier in our treatment of the countryside. I remember how, for a bit of fun,

we boys would take matches and set the heather alight. Nobody minded us doing this. It was thought to help the grass grow. My own record was three entire hillsides burnt from one match. In dry

weather, underground fires would smoulder in the peat for weeks afterwards. I never thought much of the little creatures incinerated in the process, or of the now-recognised need for any such moor

burning to be carefully regulated. That is how it was then.

When I was about six, my neighbour and schoolfriend, Alex George Morrison, taught me how to fish in the river that flowed by our house. Rarely a day would pass that we wouldn’t be out

there with bamboo-cane rods and a poor earthworm wriggling on the hook. There used to be salmon in the river when we were very small. Now they’d gone. However, one day I did catch a small sea

trout, and often we would bring home brown trout the length of our grubby hands – lean, but incomparably tasty when fried in butter with bacon.

The bigger rivers on the island did still take a good summer run of wild salmon, but most people weren’t allowed to fish in them. They all belonged to the estates and therefore were the

private property of the ‘lairds’, as landowners are called in Scotland.

My father was the community’s doctor. We also had a croft a piece – of land, usually between 4 and 40 acres, that is rented from the laird for small-scale peasant farming. I can

remember, when I was about five, telling my dad that when I grew up I wanted to be a farmer. He said that this would not be possible. He did not have enough money to buy a farm for me. Even then,

it seemed strange to me that land had a money value. But I accepted Dad’s prescription. I accepted that in my life I would have to rely on brain rather than brawn.

All the communities around us were crofting townships, and most were strung out along fjord-like sea lochs. Our eyes were sharp, and from the school bus at half a mile’s distance we could

see porpoises breaking the surface of Loch Leurbost. They pursued shoals of herring that dappled the limpid shining surface. At various times we kept hens and a cow. In winter we looked after

Tommy, the large white horse who in spring ploughed village fields in preparation for planting oats and potatoes. My sister and I cleaned out his byre, and so the manure heap, intended for our

vegetable garden, was my pride and joy. This midden, as we called it, got so hot as it composted down that the winter’s snow could never last for long, and blackbirds made holes to snuggle

down inside for warmth. I can remember taking a lesson from nature one frosty morning when my hands were frozen numb after going out sledging. I plunged them in, almost to the elbows, and warmed

them in the steaming heat. There was nothing ‘dirty’ about this that could not easily be washed off. After all, manure was the stuff of life. It was a precious commodity.

Nearly everyone spoke Gaelic and most folks, except the very old and very young, had ‘the English’ too. I grew up with one foot planted firmly in the indigenous culture. But that was

not the whole picture. My parents were very conservative politically, so much so that when, much later, I left home to go to university in Aberdeen, I thought it perfectly natural to campaign for

the Conservative Party at general elections. You see, we were an establishment medical family in the mid-twentieth century. This meant that we had much to do with those who held social power at the

dawn of the atomic age – schoolmasters, ministers of religion, and, of course, the lairds who owned the land and often happened also to be corporate magnates or military chiefs. If I had one

foot in crofting culture, the other was in the world of the laird’s lodge – ‘the big house’. Never did I feel there was any contradiction in this. My parents taught me to

treat power, especially old-money landed power, with the utmost respect. Indeed, I was groomed to be able to fit in with that milieu in life and was taught how to dress, to behave and even, through

elocution lessons (intended primarily, it is only fair to say, to correct a lisp), to speak accordingly. To this day my Lewis accent is pronounced but not strong.

The land on which we lived was in the parish of North Lochs. Looking down on the area from an aeroplane, you might wonder how anybody could live there. It comprises a beautiful patchwork of

lochs; indeed, there appears to be almost as much water as land. Most of North Lochs came under the Soval Estate, owned by two English sisters, Mrs Barker and Mrs Kershaw. It embraced 39,000 acres

– about 16,000 hectares – from the huge Loch Langabhat in the centre of Lewis right across to our east-coast villages. To the west was the 12,500-acre Garynahine

Estate. That was owned by the Anglo-French Perrins family, of Lea and Perrins’ Worcester sauce fame.

Betty Perrins claimed to be an aristocrat; she was certainly a character. She was followed everywhere by a troupe of growling, snuffling, dribbling pugs. Dogs are the only species with which

aristocrats are happy to share power. Both, in their respective ways, excel at marking out territory. So it was that Betty decided she wanted a pretty ribbon of white built around the margins of

Garynahine Lodge; in other words, she wanted a fence. And this was to be no ordinary fence: it was to be one of those double-banded joiner-crafted wooden jobs that they put around race tracks in

England. Her husband, Captain Neil Perrins, refused. It would have cost £1000. So Betty waited until he went away, withdrew £1000 of her own money, had the fence built, and when Neil

came back presented it as ‘a surprise’ for his Christmas present!

It has to be said that Betty’s efforts to hitch the Harris Tweed industry to the fashion houses of Paris did make her sufficiently popular to be elected as a county councillor. She and

Captain Neil were two of my father’s best friends. I remember my sister and I crying the night the Captain died of a heart attack on board his yacht. He was so young – of the same

generation as our father – and we loved him.

Up north, towards the town of Stornoway, with its population of 5000, was the relatively tiny MacAulay Farm Estate. This comprised little more than a very good salmon river and some rough

shooting. Edmund and Margaret Watts of the Watts Watts shipping line ran it. And south, towards the mountains of the Isle of Harris, was the 27,500-acre Eisken Estate. Rich in deer stalking, salmon

lochs and game birds, it was a sportsman’s paradise.1

Eisken was one of my very favourite places. Driving along 10 miles of a road marked ‘Private’ into the spectacular mountains of south-east Lewis was like moving a hundred years back

in time. There was no electricity. You would be greeted by the howl of hunting dogs from the kennels. Living all alone in the gaunt Victorian lodge was a quaint but kindly, craggy, tweed-skirted

old lady, named Miss Jessie Thorneycroft. She was descended from a family branch of the seventeenth-century Edward Thornycroft of Thornycroft in Cheshire. Their fortune was cast from the ironworks

of the Industrial Revolution. To this day, the family history and name survives in the yacht, mercantile and warship building company, Vosper Thornycroft.

From time to time our family would be invited down to Eisken for lunch, usually along with the Stornoway Sheriff and his family. Of course, it was his job to punish anybody caught netting

Jessie’s salmon or popping off a stag. With the Sheriff’s twin boys and my sister, there’d be four of us kids huddled around a single paraffin heater in the immense drawing room.

This boasted a billiard table, rows upon rows of stuffed stags’ heads, a tigerskin rug (or was it a lion?) and works of art including a beautiful little Thorburn sketch

of a hind. The hind’s eyes gazed out dolefully, straight at the viewer. I can remember my mother, herself an artist of considerable talent, using this sketch to teach me a curious fact. In a

picture where the subject’s eyes look straight ahead, they appear to follow you whatever angle you view it from. Little Isobel and I felt as though the hind was alive as her eyes softly

followed us round the room wherever we went. No wonder my father said that he could see no pleasure in stalking deer.

However, as was his privilege on all the estates within his area of medical practice, my father did love to fish. This was a particular honour at Eisken. Jessie Thorneycroft came from a family

line that would not allow someone onto the loch unless they could land a fly from considerable distance into a soup plate. The reciprocal side of Dad’s privilege was, of course, that our

house was often visited by guests who needed a fish hook extracted from an ear or a thumb – not everybody was up to the soup-plate test!

Such expertise resulted in dinner invitations and friendships that went on year after year. In this way I became familiar from a tender age with the lives of generals, admirals, industrialists,

lords and ladies, their chaplains and many of the great and the good who had built up or laid down the British Empire and often lamented what little was then left of it. I have to say that they

usually seemed to be fine people. True, I was expected to say, ‘Yes Sir, no Sir,’ and call the titled ladies ‘Ma’am’. But that was not so very different from the hoops

we were put through at school, where teachers also expected certain airs and graces. And there was, after all, a bit of pride to be had in meeting such important people.

I still have a school diary from 1966. It offers a little insight into these social encounters. Tangled among accounts of fishing expeditions, rabbit hunts, bonfire nights, candy-making, my

mother’s exquisite understanding of a small boy’s love of food, and watching Tomorrow’s World or The Man from U.N.C.L.E. on the newly arrived television, I recorded the

following entry on 31 August 1966:

I went out to play with Derek and Donald. I did not have much time because my mother was having guests. When the guests arrived I opened the doors for them. My mother had

told me that the man who had come was in place of the Queen in New Zealand.

In other words, this was Lord or Viscount Cobham of Hagley Hall, the Governor-General. To me, there was nothing exceptional about his visit to our home except that I had to

provide the service of doorman! It seems incredible now, but to my child’s mind there was no incongruity between hand-scything a meadow and making haystacks on a neighbour’s croft

during the day, watching the latest pictures of the moon from the Apollo rockets on television in the evening, and dining with the royal ambassador at night.

Some of the houses in our village were very modern for their times. Others were traditional – thatched dry-stone blackhouses that reeked of peat smoke. One family near us had no bathroom.

It seemed perfectly natural that they should wash their clothes outdoors in the same pools as we fished in.

I can remember waiting for the school bus one day – I think it must have been in 1966, because the village was full of men. They were all at home because of the seamen’s strike. This

was a community of mariners. Crofting has never been able to provide a living from the land alone. The plots are too small; the ground too poor. The produce of the soil has to be supplemented by

Harris Tweed weaving, commercial fishing, local part-time jobs or working away, for example in the merchant navy. Anyway, across the road from us was a family, the daughters of which were my

sister’s best friends. One of their main sources of income was from their big brother, Neilie. He was a seaman, and, with the lengthy strike on, they had very little money. Yet here they were

building a magnificent modern bungalow! How come?

On this particular day the school bus had been delayed. We’d had a late cold snap. Ice covered the road, and so we had to wait for grit to be spread by hand before the bus could make it up

the hills. Isobel and I wandered into the new house to keep warm. Nobody ever knocked on doors in those days, and many houses had no locks fitted. You went in and out of other people’s houses

as if they were extensions of your own. If you were hungry, you would be fed; if you were cold, you would be warmed by the peat fire; if you were naughty, you would be ticked off, because the

village was like an extended family.

As Isobel and I stepped inside the half-completed bungalow that frosty morning, we encountered a hive of activity. It was buzzing with men. All manner of building skill was being applied. Every

mod con was being installed. And over the open fire a string of salted ling and cod from Loch Leurbost was being cured for consumption later. Much of our diet then was local, and everything was

what would now be called ‘organic’. Dad would rarely come home from his morning rounds without a leg of lamb, a bottle of milk, homemade butter, new potatoes or even a lobster. He never

accepted salmon or venison because, by definition, these would have been poached from our friends, the lairds!

Anyway, there I was in Neilie’s new bungalow, standing there in my black lace-up shoes, flannel shorts and long grey socks, with a striped yellow scarf bulging under a navy-blue duffel

coat. On my back I carried a brown leather satchel containing books and all manner of essential accessories: a torch made myself from batteries which in those days tended to leak a white powder,

magnets, string, nails, penknife, rubber slingshots, fishhooks and line, a tin with holes in the lid full of worms for bait, and often, rattling around among it all, an apple.

Dad used to get boxes of apples regularly posted up from England. We’d get one a day – ‘to keep the doctor away’.

‘How is it,’ I asked one of the workmen in the bungalow, ‘that Neilie’s not rich but he can afford to have all of you working on his house?’

‘Ah, well,’ came the response. ‘You see, Neilie’s helped all of us to build our new houses each time he’s been back on leave. Now it’s our turn to help

him.’

I think that may have been the last communally built home in our village. Now, to comply with government regulations for housing grants and planning requirements, contractors put up most houses

by competitive tender. But you can’t just blame outside forces for the weakening of convivial old ways. Even bringing in the peats – the moorland turf dried to provide winter fuel

– is now as often as not a solitary activity. Everybody has easy access to cars and tractors these days. Many people have jobs with hours that constrain the shared use of time. Accordingly,

the old custom of making a communal effort in order that many hands might make light work has greatly declined. Yes, people have become richer. But often money has replaced relationships. These

days, there are fewer demanding common tasks around which to build community.

![]()

2. Earmarks of Belonging

It may have been observed in the foregoing pages that I sometimes make use of the collective pronoun ‘we’ when ‘I’ might have seemed more accurate. My urban friends, and acquaintances who have been on workshops about ‘owning your own stuff’, have often remarked on this. By way of a pre-emptive strike, I would therefore like to offer my excuses. I accept that to speak in the first person is very appropriate in a culture of individuality, but to do so overlooks the big picture when speaking as a person grounded in a commonality – a commun...