eBook - ePub

Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work

Theories, Methodologies, and Pedagogies

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work

Theories, Methodologies, and Pedagogies

About this book

Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work provides action-focused resources and tools—heuristics, methodologies, and theories—for scholars to enact social justice. These resources support the work of scholars and practitioners in conducting research and teaching classes in socially just ways. Each chapter identifies a tool, highlights its relevance to technical communication, and explains how and why it can prepare technical communication scholars for socially just work.

For the field of technical and professional communication to maintain its commitment to this work, how social justice intersects with inclusivity through UX, technological, civic, and legal literacies, as well as through community engagement, must be acknowledged. Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work will be of significance to established scholar-teachers and graduate students, as well as to newcomers to the field.

Contributors: Kehinde Alonge, Alison Cardinal, Erin Brock Carlson, Oriana Gilson, Laura Gonzales, Keith Grant-Davie, Angela Haas, Mark Hannah, Kimberly Harper, Sarah Beth Hopton, Natasha Jones, Isidore Kafui Dorpenyo, Liz Lane, Emily Legg, Nicole Lowman, Kristen Moore, Emma Rose, Fernando Sanchez, Jennifer Sano-Franchini, Adam Strantz, Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq, Josephine Walwema, Miriam Williams, Han Yu

For the field of technical and professional communication to maintain its commitment to this work, how social justice intersects with inclusivity through UX, technological, civic, and legal literacies, as well as through community engagement, must be acknowledged. Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work will be of significance to established scholar-teachers and graduate students, as well as to newcomers to the field.

Contributors: Kehinde Alonge, Alison Cardinal, Erin Brock Carlson, Oriana Gilson, Laura Gonzales, Keith Grant-Davie, Angela Haas, Mark Hannah, Kimberly Harper, Sarah Beth Hopton, Natasha Jones, Isidore Kafui Dorpenyo, Liz Lane, Emily Legg, Nicole Lowman, Kristen Moore, Emma Rose, Fernando Sanchez, Jennifer Sano-Franchini, Adam Strantz, Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq, Josephine Walwema, Miriam Williams, Han Yu

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work by Rebecca Walton, Godwin Y. Agboka, Rebecca Walton,Godwin Y. Agboka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section II

Conducting Collaborative Research

4

Purpose and Participation

Heuristics for Planning, Implementing, and Reflecting on Social Justice Work

Emma J. Rose and Alison Cardinal

Introduction

As technical and professional communication (TPC) moves to a more explicit focus on social justice, many scholars see this shift but don’t necessarily see their work fitting in. Others who want to move in this direction may not know where to start. And still others may want to reflect on past work to learn and look forward. In this chapter, we present a tool for scholars to help plan, implement, and reflect on the intent and impact of their research and consider ways to enact a social justice agenda.

We embrace a definition of TPC that encompasses the broad landscapes of the field, from communicating in and for organizations, using and adapting technical tools, designing experiences, using tactical technical communication in everyday life, and beyond. In this piece, we are specifically focusing on applied and empirical work in TPC that engages people in the research and design process, has direct application in organizations, and holds the possibility for impacting people’s everyday lives.

Our goal is to help all TPC researchers—whether they consider themselves social justice oriented or not—consider the choices in methodology and study design and consider how to design projects that work towards social justice. Researchers make a variety of choices when planning and implementing research, but research is never a neutral endeavor. We offer a tool to help researchers critically reflect on their intentions and their impact, to ask how their work maintains and contributes to oppression. To attempt to do social justice work, it is important for TPC researchers to ask for what purpose, for whose benefit, and to what ends does this research serve? We hope this tool provides researchers with a way to do that.

We offer a tool that is made up of two linked heuristics that can be directly applied to on-the-ground social justice in TPC work. The first heuristic examines the many purposes of doing social justice work in TPC. By understanding purpose through the categories of pragmatism, advocacy, and activism, this heuristic helps researchers consider and assess the intent and impact of any given project. The second heuristic considers participation and how researchers involve people, particularly those from marginalized communities, in the research and design process. By considering the participation of people and communities in the research process, this heuristic encourages scholars to share power and decision making with participants to develop reciprocal relationships.

Heuristics for Exploring Social Justice in TPC

When researchers make choices about what to investigate and how, there are myriad decisions that come into play. What do you hope the research will achieve? How will people, groups, and organizations be engaged in the research? What data will you collect? What tools and techniques will you use along the way?

When considering how social justice scholarship is enacted in TPC, heuristics can be helpful. Heuristics are “procedures or principles that help their users work systematically toward a discovery, a decision, or a solution” (Van Der Geest and Spyridakis 2000, 301) and are commonly used in both scholarly and practitioner settings. By providing heuristics, scholars can systematically interrogate their own work and consider ways to approach social justice-minded research within their specific context.

Building on the Conceptual Framework of the Three Ps

The three Ps—positionality, privilege, and power—make up a conceptual framework for TPC scholars engaging in social justice work (Jones, Moore, and Walton 2016; Walton, Moore, and Jones 2019). As a framework, the three Ps provide scholars an opportunity for “enacting inclusivity in TPC” (2019, 63) and facilitate “structured reflection” (2019, 64). Positionality is the recognition that our own and others’ identities (like race, gender, nationality, and so on) are complex and dynamic. Our positionality affords certain kinds of privilege, which Walton, Moore, and Jones (2019) describe as an ontological paradigm that provides a way to examine normativity and how it is embedded in “oppressive thoughts and practices” (2019, 83). Encompassing privilege and positionality, power recognizes that inequities are produced by systems of oppression, which requires a shift to “coalitional, intersectional social justice work” (2019, 105) in TPC.

Building on the three Ps, we offer our two complementary heuristics that extend the work further into practice. We refer to these heuristics as purpose and participation, and they are interconnected and designed to be used together. Simply stated, the heuristics direct the researcher to ask themselves and others within their coalition: What is the purpose and potential impact of this work? Who is participating and how?

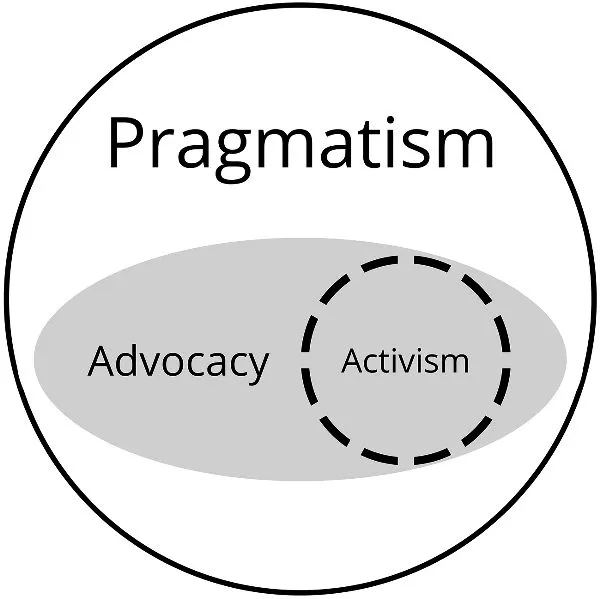

The first heuristic, purpose, helps us examine the motivation, intent, and outcomes of research. We conceptualize three overlapping categories of pragmatism, advocacy, and activism to help TPC researchers articulate their purpose for engaging in the research and examine its outcomes. The second heuristic, participation, focuses on how we involve people in our research and offers a continuum from representational to participatory engagement. In the following sections we explore both heuristics in more detail.

Researchers can use these heuristics in three ways: planning, implementing, and reflecting. They can be used to design a brand-new project and as a guide or check for each decision along the way. They can also be applied retrospectively to a project to interrogate it, learn from it, and shift future projects towards social justice in the light of the lessons learned from the reflexive application of these tools.

Purpose: Pragmatism, Advocacy, and Activism

The first heuristic (shown in figure 4.1) considers the purpose of any given social justice project in TPC and helps to critically examine the intent and impact of the work. A social justice approach to TPC considers how the practices and intent of the research works to address inequality and “can amplify the agency of oppressed people—those who are materially, socially, politically, and/or economically under-resourced” (Jones and Walton 2018, 242). Therefore, in looking at the purpose of TPC research projects, it is helpful to understand purpose through the lenses of pragmatism, advocacy, and activism. These categories frame how marginalized voices are included and represented in our work and how the agency of oppressed peoples is supported—or denied—in the projects and approaches we choose.

Figure 4.1. Three characteristics of TPC work: pragmatism, advocacy, and activism.

TPC has always had a pragmatic orientation, focusing on the direct application of practice and making improvements to it. As Jones, Moore, and Walton (2016) point out, the official, traditional narrative of TPC is “a pragmatic identity that values effectiveness” (212). However, a sole focus on pragmatism and an ethic of expediency can be damaging and dangerous (Katz 1992). Documents and designs can intentionally function to disenfranchise marginalized groups (Jones and Williams 2018) and can efficiently achieve their desired results. Interrogating and disrupting the idea that technical communication is neutral is necessary to recenter the needs and concerns of the marginalized (Haas 2012). This first heuristic helps reorient pragmatism through a social justice lens. As shown in figure 4.1, we characterize all of TPC work as pragmatic, and then nest two additional characteristics—advocacy and activism—within. Considering the work in this way helps researchers conceptualize their approach and can move their work from a sole focus on pragmatism and shift towards advocacy and activism.

The relationship between activism and advocacy is interconnected and dynamic, yet distinct. A key distinction, articulated by long-time activist Stephen Hall (2018), is that “[a]dvocacy is often seen as working ‘within the system’ whereas activism is seen as working ‘outside the system’ to generate change” (Hall 2018, n.p.). Advocacy has a long history in TPC as an “inherently rhetorical activity that seeks to constitute and engage publics through discursive processes” (Warren-Riley and Hurley 2017, n.p.). For a compelling method of advocacy in TC, refer to Grant-Davie, chapter 12 in this collection. However, not all advocacy challenges systemic inequality, which is why an activist orientation is important. Where advocacy implies support, activism requires action (Warren-Riley and Hurley 2017). As activist-educator El-Mekki explains, “advocacy alone, doesn’t alter the conditions of the oppressed” (El-Mekki 2018). Activism attempts to dismantle inequality, rather than work within the boundaries set by institutions. Activism carries more risk, since by definition activism requires putting oneself on the line. Challenging systems often leads to backlash, especially if one is already in a precarious position.

Because social justice work involves both advocacy and activism, we nested these two categories. While we define activism and advocacy separately, we see the two having a porous relationship. Represented by the dotted line around activism, we understand social justice work as an ebb and flow between the two. The amplification of marginalized voices and needs of the oppressed have to be paired with direct action (Lewis 2018). When understood as overlapping and porous, advocacy and activism together help researchers think through their purpose for engaging in social justice work. To help scholars consider the intent of their work, below we share ways that TPC scholars can intervene directly in design and build coalitions to make change.

Intervening Directly in Design

One key way TPC professionals engage in advocacy is through promoting the needs of users and readers as part of the design process (for example, refer to Lane 2018; Petersen 2018). TPC practitioners often have unique access to situations where design decisions are made. Advocacy can be used tactically to argue for the needs of marginalized users when the issue arises—be that in design decisions, policy making, or crafting content (Rose and Tenenberg 2018). Localizing is an example of social justice-based advocacy (Agboka 2013; Gonzales and Zantjer 2015; Sun 2012). As part of the process of localization, TPC professionals advocate for the design of culturally, linguistically, and locationally sensitive content (refer to Legg and Strantz, chapter 3 in this collection). As a result of this advocacy and resulting designs, marginalized communities have better access to information, leading to increased agency for these communities.

On a broader level, TPC professionals can design pragmatic tools and documents that enable activism (Agboka and Matveeva 2018). These tools are wide and varied, from apps that help to organize protests to browser extensions that help consumers avoid buying products that benefit t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Beyond Ideology and Theory: Applied Approaches to Social Justice

- Section I: Centering Marginality in Professional Practice

- Section II: Conducting Collaborative Research

- Section III: Teaching Critical Analysis

- Section IV: Teaching Critical Advocacy

- About the Authors

- Index