![]()

CHAPTER 1

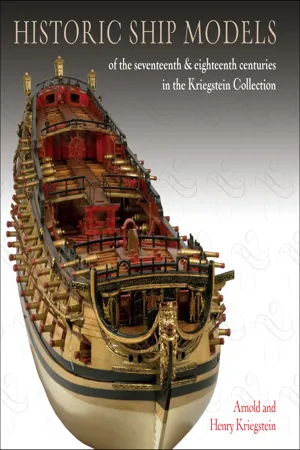

The Royal James, 1st Rate of 1671

Acquisition

FIRST RATE-SHIPS WERE the largest and most magnificent vessels in the fleet, and we had been haunted by the possibility of acquiring a model of one ever since we came across a photograph of a 1st rate from the Restoration navy that appeared in an issue of the Mariner’s Mirror in 1912, but whose whereabouts were unknown. For over twenty years we searched for the model referred to as the ‘RUSI model’ because it was last seen at the Royal United Service Institute museum in 1948. In December 1996 on a brief trip to London, Arnold stopped by the Parker Gallery, one of the few London galleries specialising in naval antiques, to chat with the proprietor, Brian Newbury, about ship models and to check his inventory. It was near closing time on Friday evening, and he had several odd models on display in the window. One was a model of a Second World War destroyer, one resembled the Mayflower and one appeared to be an unfinished model of a seventeenth-century warship. This last model had good proportions and a handsome figurehead, and Brian brought it to a table so Arnold could get a better look. Brian called it ‘the last of the Parker Gallery’s Admiralty Board ship models’. Arnold was amazed, however, at the story Brian told him when asked how he had come to acquire it. His father, Bertram Newbury, had died seven years before. Bertram had been a true connoisseur of ship models and many wonderful and important models had passed through his hands in the heyday of the Parker Gallery. The gallery was London’s oldest firm of picture and print dealers, having been founded in 1750. They specialised in naval and military subjects, and often sold models over the years.

When Bertram was literally on his deathbed, he told his son, Brian, that there was a ship model locked away in a cabinet in the basement of the shop. He admonished Brian not to sell this particular model, telling him that the longer he kept it, the more valuable it would become.With Bertram’s death the model was duly forgotten. Seven years later Brian noticed a locked chest that had been in the basement for ‘donkey’s years’. He decided to call a locksmith to have it opened.To his surprise, when the lock gave way and the cabinet doors opened, there was a dusty old ship model inside. He recalled his father’s words, put two and two together, and decided that this must be the self-same model. He dusted it off and placed it in the window for sale. This was one week before Arnold stopped by. After relating this story, Brian was ready to close shop, so Arnold took photos of the model and said goodbye. Despite the intriguing story, the model had several parts clearly made of new wood as well as some apparently unfinished areas at the stern. Arnold suspected it was a fine copy made in the last century, and he flew home the next day.

The Royal James has a relatively long beak, as well as considerable sheer at the bow and stern, consistent with its early date. The long gun decks, resulting from the placement of 15 generously spaced guns on the lower deck, produce a low-slung profile uncommon in such a large three-decker.

This model has the unusual feature, visible here, of narrow gangways on either side of the poop deck leading from the bulkhead stairs approximately halfway to the stern. This provision allows the headroom in the officers’ cabins to remain as high as possible.

The bowsprit passes to the starboard of the stem so that the butt end can be stepped alongside the foremast on the lower gun deck. The foremost gun port on the main gun deck is placed between the cathead bracket and the rail, enabling a forward arc of fire. The anchors are stowed, and the anchor buoy can be seen secured to the foremast shrouds.

A lovely feature of this model is the bold acanthus leaf decoration painted along the frieze planking. Circular wreaths around the gun ports were a standard feature at this time, having largely replaced the square port wreaths that were common in pre-restoration ships.

Three days later, on Tuesday evening after dinner, Arnold sat down to examine the newly developed photos he had taken on his trip. On top of the pile was a broadside view of the model, but it was underexposed and in near silhouette because the flash on his vintage Leica had failed to fire. The profile seemed oddly familiar. After several seconds Arnold realised that this model looked just like the missing RUSI model, and in the next moment it dawned on him that this was the RUSI model! After twenty-five years of searching for a model that was only known from dark black-andwhite photos, Arnold had come across it in living colour and not recognised it. The pieces of new wood could now be explained as part of the restoration undertaken by Robert Spence in the 1930s. Arnold immediately grabbed the phone to give Henry the incredible news.We were astounded that the model had finally been found and was for sale, but also concerned because we had not bought it yet! Arnold spent the night pacing sleeplessly until 4am (9am London time), when he called the Parker Gallery. An assistant told him that Brian was not expected for one more hour and kindly offered to have him call when he arrived. Arnold had rarely been more anxious than he was for that long, long, hour. The phone rang promptly at 5am. ‘Good morning Brian,’ Arnold said, and after a short pause, Brian, sounding quite surprised, replied, ‘How did you know it was me?’ We laughed at this, but Arnold quickly brought the conversation around to the model. Within twenty-four hours we had not only found, but had purchased the missing Royal James model. This was a time for celebration. But there was one more obstacle that could scuttle our hopes of ownership. As we had learned once before (see Chapter 6), buying an important model in England can be much easier than bringing it home. This model would require an export licence.

The Export Licensing Unit of the Department of National Heritage is charged with issuing export licences for works of art of potential cultural, historic or aesthetic importance. The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art meets regularly to consider arguments for and against export of important objects, taking into account the input from pertinent authorities. The expert for nautical works of art at the time was Simon Stephens of the NMM, and he was consulted in this case. Simon decided that the model merited a closer look, and he made arrangements to inspect the model on the Parker Gallery premises. Once before, we had the export of a model opposed by the NMM, and we knew that the decision could be influenced by how much the model had been altered by restoration. Losses were acceptable, but undetectable alterations would undermine the historical reliability of the model as an authentic example of Restoration warship design. How much of the existing model was original, and how much the work of Robert Spence? To complicate matters, Spence was a master craftsman perfectly capable of making seamless additions or alterations to a model. Proof can be found in the NMM storage depot, where there is a lovely model purchased by the museum at auction in 1944 that was believed at the time to be an authentic seventeenth-century Admiralty Board model of the St Albans. However, an identical model also purporting to be the St Albans subsequently appeared in the private collection of Robert Spence. In fact, Spence had been the consignor of the St Albans model purchased by the NMM. Spence died in 1964, and to this day it is not entirely clear which, if either, of these models is original. Possibly Spence had taken apart one authentic model and reproduced pieces to make two identical models incorporating some of the original in both! It thus came as no surprise to us that Simon planned to subject our Royal James model to a thorough inspection, even going so far as to probe the interior with a surgical endoscope.

Nearly all warships in the time of Charles II sported the royal arms beneath the taffrail. In three-deckers, including the Royal James, these were enormous carvings that dominated the stern decorations. The coat of arms shown here is a seventeenth-century replacement (the original having vanished long ago) but is an impressive example of miniature carving. The craftsman has made no concession to the small scale and has included every detail that would appear in the full-size carving.

We had spent over twenty years searching for this model, and while none of our efforts led us to it, we had accumulated some interesting tidbits of information. For example, we had learned that when Spence restored the model in the 1930s he left a note inside detailing what he had done. It now occurred to us that this note could have a bearing on the export licence because it could enhance the historical importance of the model by specifically indicating exactly what had been done to the original. We decided to leave nothing to chance. Arnold made plans for a quick visit to London intending to find the letter before Simon’s inspection and read it over. Only then would we know how damaging it might be to our case. To be perfectly honest, the thought of removing the note also crossed our minds, but we resolved not to do that. As it happened, Arnold never found the note, but not for want of trying. He spent two hours on a Saturday morning carefully inspecting and photographing every square inch; even taking the model partially apart, but to no avail. Arnold was very disappointed. He had flown to London to accomplish this one task and had failed. But Arnold was fairly confident that Simon would do no better, and that the letter, if it existed at all, would not be found and would not figure into the export decision. Many months later, however, as Arnold was once again going over the events of that morning, he suddenly realised where Spence may have hidden his note.When Arnold had lifted off the main capstan (a drum-like device used for hauling anchors and shifting guns), he noted that the partners for the capstan spindle, usually two pieces of deck planking with a round hole between them, were in this case built up into a tiny box-like structure. A box! Arnold could think of no reason why this piece should not have been a simple thin plank. The miniature box was only 1in square and ¼in thick, and he decided it must contain the fabled note.

This photograph provides a perspective that one might have had when approaching the stern of the Royal James by barge. Stern and quarter galleries were enclosed at this date. Open galleries and balconies are features that would appear only at the end of Charles II’s reign. The Jacob’s ladders, ...