![]()

Part I

INTRODUCTIONS

![]()

INTRODUCTION

On New Year’s Day 1939, Manfred and Malka Goldfisch stepped ashore into the heat of a Trinidadian winter.1 In Port of Spain it was 30 degrees centigrade and brilliant sunshine. Their journey to freedom had started two weeks earlier, as they left an ice-bound Hamburg to begin their lives as Jewish refugees in the Caribbean:

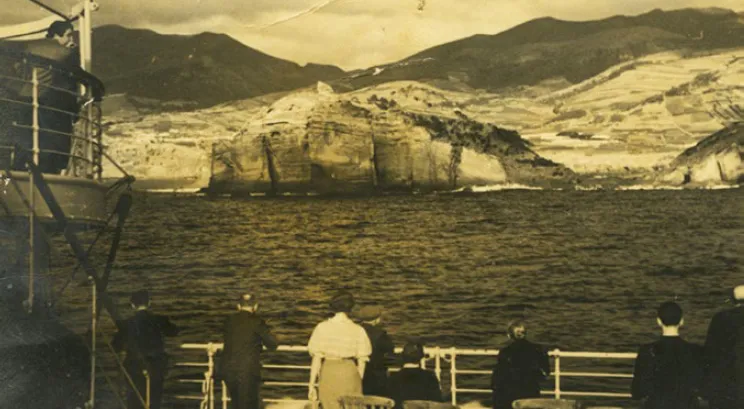

On a cold day in Koenigsberg, [there was] nothing else left but to say goodbye to a few friends, and at the end of November we were ready to leave the now grey and wintry Baltic … We boarded a train to Cologne to spend a last week with my parents, and then the sad moment of parting had to be faced. There were no tears, no sighs, only grim faces all round, when the whistle blew, and the Hamburg express started to pull out of the station … The excitement of the imminent departure kept us awake, and it was almost morning before our eyes closed. At 7 am the desk [in the hotel] woke us as arranged, and an hour later a bus took us to the quay – the great adventure was about to begin. It was bitter cold … The liner was to sail at noon, and icebreakers were busy keeping channels open so that departure would not be delayed. In spite of the biting cold I could not resist to go on deck to watch tugboats getting into position to pull the giant hulk into the stream. Then a shudder went through the ship as the powerful diesels down below started their run that would not stop for fourteen days and nights. I watched as, to the sound of grinding and crushing ice, the liner slowly edged away from the ice-covered concrete wall of the quay. A strip of black water appeared; we had lost contact with German soil. With long angry blasts of their sirens the tugs began to pull, and we were on our way.

Figure 0.1 Manfred Goldfish and Malka Goldfish (later Wagschal née Golding) a year before leaving Germany for Trinidad in 1937. From The Last Goldfish. Umbrella Entertainment, 2017. Screenshot. Published with permission.

Exactly a fortnight after the couple arrived, with mounting numbers of refugee arrivals, Trinidad, alongside other British colonies, placed a ban on the further admission of refugees from Europe. The Goldfisches had married just three months earlier, and immediately started to arrange for passports and look for places to which they might emigrate. After ‘Kristallnacht’, the Nazi pogrom on the night of 9/10 November 1938, with its thousands of arrests, the looting and destruction of Jewish homes and property, and the burning of synagogues across Germany, Manfred felt it too dangerous to remain. After a fruitless attempt to get visas for the United States through a relative there, in desperation they contacted shipping agents who sold them the last two tickets for a berth on the SS Cordillera, bound for Trinidad. It would cost Manfred almost all he had left in his bank account; but watching the ‘still smouldering ruins’ of one of the synagogues, he paid up. Saying goodbye to his parents in Hamburg, he did not register the full importance of the farewell. In a memoir written years later, he recalled: ‘Gradually the figures of my dear parents Lina and Eugen Goldfisch faded into the steamy mist of the big railway junction and I had a feeling, almost a premonition, that I would never see them again’.2 In 1942 his parents were deported to Theresienstadt where they both died, within a year of each other.

The Goldfisches’ experience of escaping Nazi Germany is part of the much larger story of the plight of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazism, of whom, I have estimated, several thousand found sanctuary in British colonies in the Caribbean.3 This book is called Nearly the New World because for most refugees who found sanctuary, it was nearly, but not quite, the New World that they had hoped for. The British West Indies were a way station, a temporary destination that allowed them entry when the United States, much of South and Central America, the United Kingdom and Palestine had all become closed. For a small number, it became their home. This is the first comprehensive study of modern Jewish emigration to the British West Indies. It reveals how the histories of the Caribbean, of refugees, and of the Holocaust connect through the potential and actual involvement of the British West Indies as a refuge during the 1930s and the Second World War.

Figure 0.2 View from the SS Cordillera (1938). From The Last Goldfish. Umbrella Entertainment, 2017. Screenshot. Published with permission.

This book is also the first to provide a panoptic overview of the different waves of Jewish immigration to the British West Indies. It covers migration from Eastern Europe and Nazi Germany in the 1930s, to the wartime period when refugees crossed the Atlantic from southern France, Portugal and Spain, and Britain brought Jewish refugees to Caribbean colonies as in-transit refugees, internees or evacuees. It addresses the role of the West Indies as a refuge by exploring the actual reception of refugees, the impact on the West Indian economy, and the responses of a post-slavery society (still ruled within a colonial system where decisions on immigration, defence and security were made in Whitehall). As such, it also illuminates both accommodating and restrictive aspects of British immigration policy, as the British West Indies were part of the Crown Colony system of government.4 Through researching the archives of the major Jewish aid organizations in the United States and Britain, including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC or ‘Joint’), HICEM, the World Jewish Congress, the Central Council for German Jewry and the Chief Rabbi’s Emergency Committee, I have unearthed new evidence of the crucial role these organizations played in aiding migration and supporting refugees. The themes in this book also have direct relevance to the refugee crisis of the early twenty-first century: the impact of refugees on island communities; the agency of refugee organizations; how competing priorities between government departments influence British refugee policy; refugee integration and acceptance in a post-slavery society; and the refugee experience itself.

Jeffrey Lesser’s Welcoming the Undesirables: Brazil and the Jewish Question noted that historians have tended to ‘lump all but the largest numerical communities into the category of “exotica”, and thus not worthy of careful study’.5 There has, in fact, been an increased focus on Jewish refugee migration to colonial and ‘exotic’ settings, most recently by Jennings’ Escape from Vichy and Kaplan’s Dominican Haven.6 There have also been attempts to globalize Jewish studies by investigating transcultural and hemispheric American dimensions of Jewish experience, and by giving more emphasis to Sephardim; this study therefore adds an important new dimension to the Jewish Atlantic scholarship that has largely focused on the early modern period.7 Caribbean studies itself has recently moved beyond an exclusive focus on African and South Asian diasporic presences to address other populations such as the Chinese and the Irish; however, the Jewish presence in the Caribbean and Jewish forms of creolization have been quite neglected by Caribbeanists, with the exception of some work on the early modern Dutch Caribbean. While there are interesting comparisons that can be drawn between the treatment of Jewish refugees in the French, Spanish and Dutch Caribbean, this study restricts itself to the British West Indies.8 Also beyond scope of this study, but will remain for other scholars to explore, are the interesting comparisons to be made between the treatment of Jewish refugees and internees across the British Empire, where local conditions led to internment policies being carried out differently.

What happened to refugees in the 1930s has resonated in discourse about sanctuary ever since. In 2015, UN Human Rights Commissioner Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein emphasized the dangers of turning away refugees from European shores, and compared the twenty-first century refugee situation to Europe in the summer of 1938, barely four months before Manfred and Malka Goldfisch left Germany for good. Recalling the Evian Conference, held in the French spa town of Evian les Bains in the July of 1938, Al Hussein criticized Britain and other European politicians for using dehumanizing language that, he claimed, ‘has echoes of the pre-Second World War rhetoric with which the world effectively turned its back on German and Austrian Jews, and helped pave the way for the Holocaust’.9 By the time of the Evian Conference, far-flung destinations such as Trinidad were becoming familiar in the lexicon of place names consulted by German Jewish families desperate to emigrate.10 As strict immigration regulations were already in force around the world, opportunities for emigration became more limited, unless one had capital to invest, relatives or friends willing to provide guarantees, or employment offers. From being first regarded as obscure, destinations like Trinidad and Shanghai that did not require visas became the last chance for those still able to leave Nazi-occupied Europe. By that summer, the German Jewish mindset had also changed: after long believing that the antisemitic legislation and persecution introduced in 1933 would be reversed, by now the population of German Jewry who had not yet left had realized that emigration was the only viable response.

My father was a child refugee from Germany, and coming to Britain saved his life and that of his parents, brother and two grandmothers in 1937. Their entry rested on the serendipity of a British passport officer at Dover ignoring the fact that their entry permit was out of date by one day. They were among the approximately eighty thousand Jewish refugees admitted into Britain before the outbreak of war.11 For those unable to enter the United States or Great Britain, these unlikely places of refuge across the British Colonial Empire, from Shanghai to Hong Kong, from Tanzania to Sierra Leone, from Trinidad to British Guiana, undoubtedly saved tens of thousands of lives but were clearly places of last resort for desperate refugees.12

I first became interested in this story when searching the Tate & Lyle Archive in Silver Town, London, for papers relating to the seventeenth-century Caribbean. I was researching the Jewish community in Barbados from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, and found a file of correspondence about the internment of one Edward Schonbeck, a refugee chemist from Berlin working for WISCO (West Indies Sugar Company). A number of years later, when I began to research this book, I found files on his internment in the National Archives in the UK (TNA) and managed to contact him. He was the first refugee from the West Indies whom I met, and he told me his story sitting in the Mozart Cafe on the Upper West Side of New York. I subsequently presented an ‘Archive Hour’ broadcast for BBC Radio 4, ‘A Caribbean Jerusalem’, including interviews with former refugees and with some West Indians who remembered them in Trinidad and Jamaica. More recently, I have been in touch with a number of descendants, including Su Goldfish, the daughter of Manfred Goldfish, whose documentary, The Last Goldfish, was selected for the Sydney Film Festival in 2017.

Refugee narratives are threaded through this book. Using these sources extensively helps to tell a largely untold story, and fills in the gaps in the historiography and in collective memory. While official archives of organizations and governments tell much about the policies and decisions taken that materially impacted refugees and British West Indians, it is through their own voices that we can uncover the many conflicting stories of refugee survival and experience, of frustration and anguish, of pragmatism and adaptation. In contrast to more established narratives of refugee migration to countries such as the United States and Britain, many of these voices have not been heard before, and are part of the hidden history of Jewish migration to and from the Caribbean.13 In Atina Grossmann’s work on ‘Asiatic’ refugee migration, these stories of circuitous routes around the globe, like hers, ‘render[s] the history of the Holocaust, its refugees and survivors, transnational and multidirectional in new ways’.14

This book takes a roughly chronological approach. In Chapter 1, I lay out the contextual drivers for the story to unfold. This includes an overview of how the Crown Colony system operated, of the political and economic changes in the British West Indies during the 1930s and 1940s, and of the formation and background to those Jewish refugee organizations that will be key players in this book. I start by discussing the anxiety expressed by the British Colonial Office from the 1920s about whether the Empire had sufficient immigration legislation to guard against unwanted migration. At this point, the unease was in Eastern Europe, where the world recession, alongside rising nationalism, had created the conditions whereby the Jewish population in particular was becoming increasingly impoverished and marginalized. Once the United States had instigated its hugely restrictive quota law of 1924, the most obvious emigration route had mainly closed.

From the 1920s, a steady accretion of legislation across the Americas and the Caribbean followed the United States’ lead. During this period, a significant number of East European Jews, unable to enter the Americas, came to and made their homes in West Indian colonies, including Barbados, Trinidad, Jamaica, British Guiana, British Honduras and Dominica. They were more successful, in general, in putting down roots and establishing small businesses than the Jewish refugees from Nazism who followed. Although most were not interned, once war broke out they effectively became exiles, unable to go back to their country of origin.

The tensions that existed between Crown and colony are highlighted in this chapter, as the call for ...