![]()

1

HISTORY, HIS STORIES, AND HISTORIOGRAPHY

When local author Laura James related that, “Nate was a friendly person … but his life story was never told, even by his best friends,” she pinpointed the primary difficulty in trying to write an authoritative Harrison biography—there is remarkably little reliable information (1958: 5). In fact, there are struggles of many types in any attempt at constructing an accurate history. Carl Becker insisted nearly a century ago that, “[History is] an unstable pattern of remembered things redesigned and newly colored to suit the convenience of those who make use of it” (1935: 253–54). Despite the many inherent challenges in its construction, the following overview of Nathan Harrison’s life is offered as a starting point for detailed discussion of who he was, how he came to California, and why he became revered as a legendary pioneer of the Old West.

Biographical Synopsis

The child of Ben and Harriet Harrison, Nathan “Nate” Harrison was born into slavery in Kentucky in the 1830s. Virtually nothing is known of his childhood. As a young man, he traveled west with his owner, Mr. Harrison, during the early years of the Gold Rush (1848–52). Nathan Harrison worked as a miner in Northern California’s mother-lode region in the 1850s and early ’60s. Following the death of his owner, Harrison migrated southward toward Mission San Gabriel in the 1860s, working as a rancher, timber man, and laborer. In the 1870s, he frequented many parts of San Diego County, including Pauma Valley and other northern inland areas, as well as the city of San Diego; Harrison found regular work all over the region as a rancher, timber man, laborer, cook, and shopkeeper. It was during this time that Harrison married an Indigenous woman with children from a previous union; their marriage was brief, although he would remain close to her family. From 1879 to 1882, Harrison patented and lived on land at Rincon, near the base of Palomar Mountain and adjacent to Pauma Indian territory; this acquisition made him the first African American homesteader in the region. In 1882, Harrison sold his property to Andreas Scott and left Rincon, although he stayed in the general area and worked at Warner’s Ranch and in Temecula for a few years. Harrison married again in the late 1870s or early ’80s, this time to an Indigenous woman named Dona Lavierla; they were not together long. In the late 1880s, Harrison made his home two-thirds of the way up the west side of Palomar Mountain; he claimed the tract’s water in 1892 and homesteaded the land in 1893. Harrison lived on Palomar Mountain from at least the late 1880s through 1919. During his early years on the mountain, Harrison was busy in many local industries, including shepherding, cattle tending, bee keeping, and horticulture. In his later years on Palomar—especially after the county widened his road and made it a public highway in 1897—he became a popular attraction for tourists, visitors, and friends, who helped to sustain him with regular gifts of food and other supplies. During a visit by acquaintances in October of 1919, an ailing Harrison was convinced to leave the mountain and receive medical attention. Now in his eighties, he lived for an additional year in the San Diego County Hospital before dying there on 10 October 1920. Harrison’s body was immediately interred in an unmarked grave in Mount Hope, the city cemetery.

The Nathan Harrison Historiography

A key step of contextualized history or historiography is transparency, especially with regard to chronologies involving contradictory elements. The process employed here involved separating probable histories from obvious fiction while incorporating a majority of plausible options. Once all of the accounts were meticulously inventoried, dissected, and studied, we could evaluate each story and even individual narrative elements. This level of analysis makes it possible to ascertain the most likely scenario while still incorporating multiple perspectives.

The historiographic process also involved noting how authors of individual accounts apparently drew information from others. This was often the first step in pinpointing when historical fallacies started and mapping their consequent growth. Alternative histories were not entirely eliminated from Harrison’s biography; however, they were explicitly de-emphasized due to certain dubious details. Whereas the next chapter on myth-making explains how and why certain fictions became told as historical fact, the remaining historiographic section of this chapter focuses on which narratives were seemingly the most accurate and why. Individual sentences from the biographical synopsis introduce each historiographic section to ground the discussion in the ultimate conclusion.

The child of Ben and Harriet Harrison, Nathan Harrison was born into slavery in Kentucky in the 1830s.

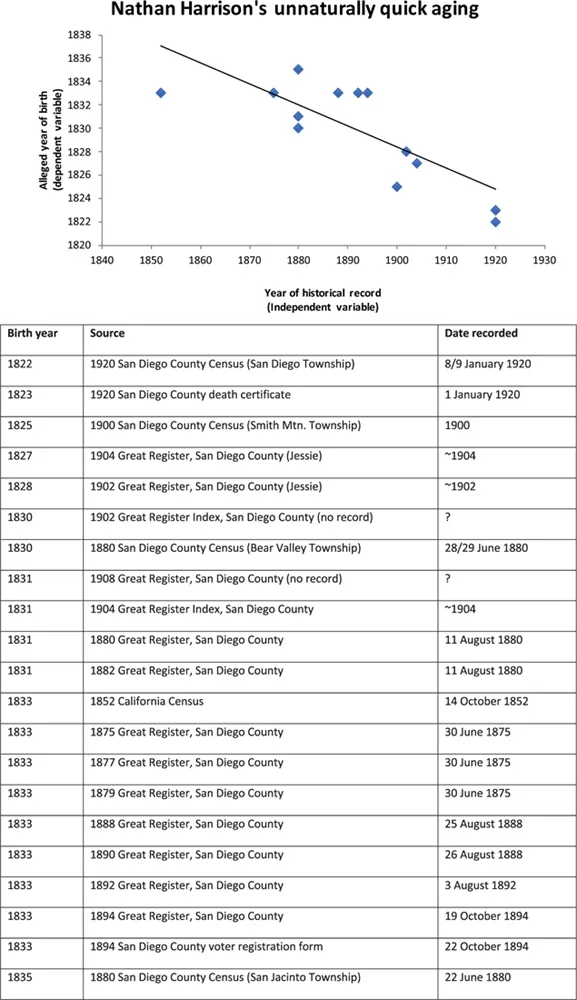

The most reliable historical sources, which include censuses, great registers, and other government documents, placed Nathan Harrison’s year of birth between 1822 and 1835 (Figure 1.1). Even during his lifetime, there was a clear pattern of Harrison’s exact age being disproportionately exaggerated over time. Whereas the rest of us age one year with each passing twelve-month period, Harrison’s birth year was recorded significantly earlier with each new calendar. Close examination of the curious case of Nathan Harrison revealed that, according to government documents, his alleged age unnaturally accelerated with each subsequent record. During the 1870s and ’80s, he was purportedly born in the 1830s; however, censuses taken in the 1900s claimed a birth year in the 1820s.1 It is worth noting that these were official and contemporaneous government documents, not embellished mountain fables told generations after his passing. The “historical facts” were already clearly under manipulation during Harrison’s lifetime, especially in his last few decades on the mountain.

Nathan Harrison was most likely born in Kentucky. Fifteen of sixteen contemporaneous government records pinpointed Kentucky as his state of origin, whereas the lone outlier listed Alabama.2 Although Virginia, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee were mentioned in secondary accounts, none of these states were corroborated in the more reliable historical sources.3 Harrison’s state of origin was an important foundational fact for his biography. Successful identification of it was also a key element in evaluating competing stories regarding the identity of the slave-owner who brought Harrison to California as the two distinct alleged owners were from different states. Ironically, only the last official record—his death certificate—included the names of Nathan Harrison’s parents, Ben and Harriet. All other census records, registers, and other governmental receipts failed to identify them.

Virtually nothing is known of his childhood.

Contemporary mountain residents who knew Harrison well emphasized that he rarely spoke of his pre-California life. They repeatedly alleged that Harrison was especially recalcitrant about his ordeals as a slave. Harrison friend and Palomar neighbor Robert Asher avowed with unwavering certainty, “Of one thing I am sure, however; not one word did Nate say about his old Kentucky home, or of the trek to California” (c. 1938: no page numbers).4 Secondary sources also related Harrison’s reluctance to discuss his antebellum past. Virginia Stivers Bartlett quoted a rancher named “Jack” as declaring that, “Give Uncle Nate a drink … and he would tell you more about the county than anyone in it. But never a word about himself” (1931: 23). Extensive research into slave records, censuses, and other historical sources failed to locate any information that offered direct insight into Harrison’s pre-adult years. This was hardly surprising as most African Americans did not appear in federal censuses until the end of the Civil War, and various slave schedules of the middle-nineteenth century were often irregular and fragmentary.

Figure 1.1. A table and scatterplot of contemporary government records show that during his lifetime Harrison’s accepted birth year gradually changed from 1835 to 1822. (Courtesy of the Nathan “Nate” Harrison Historical Archaeology Project.)

As a young man, he traveled west with his owner, Mr. Harrison, during the early years of the Gold Rush (1848–52).

One of the most important discoveries of the Nathan “Nate” Harrison Historical Archaeology Project was not a rare artifact but a recently scanned and uploaded census record that was not known to project researchers until the spring of 2018, a decade and a half after our work began. The 1852 California census for Santa Clara County listed Nathan Harrison as a nineteen-year-old black male, born in Kentucky but having last lived in Missouri. Santa Clara County was one of the original counties in California at statehood and stretched from Santa Cruz in the west to Merced and Stanislaus to the east; it was adjacent to many areas that produced sizeable veins of precious metals and saw expansive growth during the California Gold Rush. Each of these four traits listed for Harrison in the record—his name, year of birth, state of origin, and gateway state to the West—was echoed in the most reliable historical sources. Of course, presence on that census record did not establish when Harrison arrived in California, just that he was living there in 1852. Furthermore, the 1850 California census did not include an entry for Nathan Harrison. These crucial pieces of information suggested Harrison came to California between 1850 and 1852.

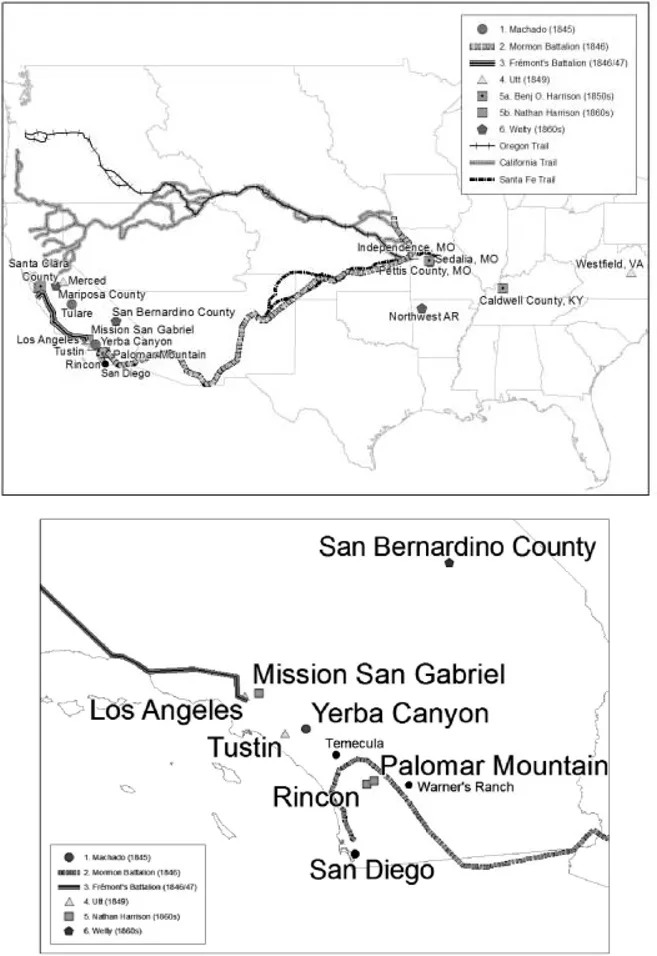

While all histories of Harrison agreed he migrated from the American South to California, there was significant debate as to when the westward trek took place. Many primary and secondary narratives suggested he and his owner were part of a team that joined the California Gold Rush (1848–55), but others put Harrison in the West for the first time either before 1848 or after 1855. Overall, there were six general scenarios for Harrison’s journey across the US; they are discussed in chronological order and evaluated for accuracy on a case-by-case basis (Figure 1.2).5 The first posited a mid-1840s pre-Mexican-American War arrival date. The second specified an 1846 journey that ultimately united Harrison with the Mormon Battalion that marched from Iowa to San Diego. Similarly, the third denoted a late 1840s Mexican-American War period/pre-Gold Rush cross-country trip that ended with Harrison joining Frémont’s Battalion sometime between 1846 and 1848. The fourth involved a Virginia-to-Los Angeles journey that ended on Christmas Eve of 1849. The fifth and best-corroborated scenario claimed a late 1840s/mid-1850s heart-of-the-Gold-Rush trip that brought Harrison to California’s mother-lode region. The sixth placed Harrison on an early 1860s wagon train from the Midwest. Since each trip was largely tied to different routes, personnel, and purposes, it was often difficult to combine narrative details and find inclusive historiographic compromises.6 As a result, certain scenarios just seemed more likely than others.

Figure 1.2a/b. Maps of different potential Nathan Harrison migration scenarios against a backdrop of the United States in 1850: the first offers an overview of the different scenarios on a nationwide level, and the second focuses on Southern California. (Courtesy of the Nathan “Nate” Harrison Historical Archaeology Project.)

The tales of Harrison’s life were not told in a vacuum. Many of the mountain’s best storytellers were well aware of rival narratives and the rampant creative license frequently employed in such chronologies. For example, in a 1959 interview, Harrison friend Louis Salmons poignantly justified his biographical account over others with the following opening proclamation: “Well, I’m not as big a liar as some of the rest of them. All I know is what the old man [Harrison] told me a thousand times” (Hastings 1959b: no page numbers).7 This statement simultaneously emphasized the degree of invention and exaggeration in many accounts of Harrison and avowed Salmons’s alleged authentic firsthand knowledge of Harrison’s past.

Scenario #1: Pre-1845 Arrival

Harrison friend Robert Asher wrote a series of unpublished manuscripts during the 1930s and ’40s. Many of his descriptions included eye-witness accounts of life on the mountain during the nineteenth century. Asher quoted former Nathan Harrison nephew Frank Machado with the earliest claim of Harrison being in California. In an extended passage, Asher related that, “Machado is an Indian owning a bit of farm land lying between the Indian Reservation of La Jolla and the Henshaw Dam … He is a very interesting talker and is well posted on the mountain’s history for some time back” (c. 1938: no page numbers). Asher specified in one Sunday afternoon interview with Machado:

We got [Machado] started talking about “Mister Harrison,” as he called Nate. Said Machado: “… Mr. Harrison was working in Tulare County in 1845, was threatened with death, so went to [Yerba] Canyon near Santa Ana. Married Fred Smith’s mother, a Lake Pechanga8 woman, then Dona Lavierla, my aunt, in 1882.” (c. 1938: no page numbers)

This brief and disjointed two-sentence summary contained a wealth of important information. Furthermore, other reliable sources echoed the overall sequence of Harrison moving southward from a mining community (like Tulare County) in the center of the state to south-lying Yerba Canyon near Santa Ana.9 In addition, some of Harrison’s closest friends insisted he had married multiple Indigenous women in succession, although his exact matrimonial history would be a subject of great debate.

The initial date of 1845 in the Asher/Machado passage was potentially problematic. Semantically, Tulare County was not officially created by the US government until 10 July 1852, and the town of Tulare was not founded until 1850. Furthermore, there was very little pre-Gold Rush (pre-1848) industry in this particular area of Mexican territory in 1845. While it is true that in 1841 the Mexican government began to allow foreigners to apply for land grants, the Tulare region was not in high demand (Engstrand 1993: 65–66). The Asher/Machado narrative offered no other details supporting why Harrison would venture to Tulare and end up working there in the early to mid-1840s. Less than a decade later, however, Tulare County would be a hotbed for mining activity. Asher was usually a reliable source, but in this case, he was quoting someone else and did not comment as to the veracity of the information. Furthermore, none of the other accounts supported an early or mid-1840s presence of Nathan Harrison in California. The combination of a seeming geographic non sequitur in the yet-to-exist Tulare County, a lack of supporting information for the early date, and a wealth of competing narratives undermined the credibility of this particular scenario.

Scenario #2: 1846 Arrival

Bertram Moore, an Assistant San Diego County Engineer from 1922–50, scoured County Supervisor records for interesting historical notes and identified an unattributed and unverified account of Nathan Harrison joining the Mormon Battalion on its famed trek across the western US to San Diego. He reported that, “In 1846—Nate was about 16 years old—Harrison landed in one of those towns along the route followed by the Mormon Battalion on their march to Calif. He joined as a helper (servant to some officer)” (B. Moore, n.d.: no page numbers). The Mormon Battalion primarily consisted of over five hundred Latter-day Saints in Iowa who formed the only religion-based unit to serve in the United States military. Starting in July of 1846, they marched nearly two thousand miles to San Diego to support the US in the Mexican-American War of 1846–48. The battalion never saw action because the peace treaty was signed twenty-six days in advance of their 29 January 1847 arrival. Nevertheless, their march remains one of the longest in US history.

The story of the Mormon Battalion has come to represent two important ideals in early US American history: 1) religious freedom and 2) the arduous trek westward. Though Harrison’s celebrated biography embodied similar themes of liberty and death-defying challenges in the Old West, there was no supporting evidence of his joining the Mormon Battalion in any capacity. No other sources confirmed this narrative and many countered it. Furthermore, thorough historical documentation on the Mormon Battalion offered no evidence of him being on any company roster, arrival list, or record of any kind.

Scenario #3: 1848 Arrival

Author Virginia Stivers Bartlett claimed that Harrison came to Southern California “in 1848 with Frémont’s Battalion” in her article, “U...