![]()

Part I

The Intellectual and Political History of a Human Garden (1880s–1980s)

Human laboratory, experiential landscape, breeding ground for the ‘elite class’ – this is how you should see the garden-city Ungemach.

—Suzanne Herrenschmidt, speech at the awarding of Alfred Dachert with the Legion of Honor, Strasbourg, 11 December 1947

![]()

Chapter 1

The Acceptance of a Eugenic Experimentation

A Socialist Paradise for the Middle Class

On Sunday 5 October 1923, a new neighbourhood was publicly unveiled in Strasbourg – ‘Ungemach Gardens’, a subdivision of forty houses that was built in the northeastern part of the city, barely two kilometres away from the cathedral, on the Wacken lands that the military had liberated.1 The site was ‘crossed by a small river – the Aar – and the water and old trees gave the site a picturesque and relaxing feel’.2 In line with both the latest standards of comfort – running water, bathroom and laundry room – and the popularity of regional architecture at the time,3 ‘the detached houses, with their terracotta colour, large rooves, outside staircase and white shutters, resembled the houses of small Alsatian cities from 1830’.4

The crowds came. Two hundred and ninety-two households submitted applications during this first phase to rent out forty houses. Interest did not wane as one hundred additional houses were built in the following years. Granted, the city offered young ‘middle-class’ couples rents that were a quarter cheaper than those of the city of Strasbourg’s housing office, not to mention free benefits like the garden.

At first glance, the Ungemach Foundation’s generous offer was among a raft of initiatives seeking to address the shortage and high cost of housing. The Great War’s destruction aside, Strasbourg saw its population triple during Germany’s annexation (1871–1919). Before the war, the reformist mayor Rudolf Schwander had seen through the creation of new, wider roads in the city, embellishment and improved sanitation of buildings.5 After the city’s return to France in 1918, Jacques Peirotes, the city’s first socialist mayor, increased housing aid. Over his sixteen years at the helm, he proved to be ‘the biggest builder of the century in Strasbourg’.6

After Paris and Lille, Strasbourg was the third French city to secure, under the law of 21 July 1922, the reclassification of four-fifths of the former fortified city – in this case a real estate holding of over five hundred hectares. The Cornudet law of 1919 directed each city to implement a development plan:7 while the reclaimed space was to be devoted to a ‘green belt’ non aedificandi,8 the municipality greenlighted the full array of the era’s social housing – low-rent housing known as Habitations à Bon Marché (HBM), allotments and garden-cities.9 Ungemach Gardens was among the latter. The mayor provided the land free of charge and built the roads. In return, the Ungemach Foundation committed to maintaining low rents and transferring the housing development property to the city on 1 January 1950.10 Initial rents, which tracked the municipal cost of living index, ranged between 2,760 and 3,200 F annually. The target market was the small middle class: at the time, the average monthly salary in France was 2,135 F.11

The Peirotes policy was favoured by a legal framework that was specific to the reintegrated French Alsace. Resulting from the Gemeindeordnung of 6 June 1895,12 it provided greater flexibility than national legislation13 and allowed the mayor to pursue broad economic and social interventionism.14 Social housing played a major role here. A generation before the institution of social security in 1945 would relegate it to playing second fiddle, social housing was heir to an era when the ‘social question’ was primarily an urban issue. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, concerns about containing the vices of the working class and regulating rural emigration to the cities and new industrial basins focused on housing policies. In contrast to the degrading assistance provided to the ‘destitute’, these policies were meant to help the ‘working poor’ build an independent and responsible life. This social policy choice was reflected in an 1894 law that offered access to affordable housing through ownership rather than tenancy, principally via municipal and private funding.

The moderate socialist Peirotes represented the left wing of the reform network that had been developing and coordinating this policy since the 1890s. He was one of the figureheads of municipal socialism,15 wherein housing played a key role for redistributive and health purposes, as well as for pork-barrel politics. Held up to public obloquy by the communists for his ideological positioning to the right of his party, the French Section of the Workers’ International, the socialist Peirotes was forced to seek a constituency beyond working-class voters.16 Just like the social democratic party across the Rhine,17 he turned to the ‘middle class’ that had become a vibrant force due to both the active political mobilization of artisans in Alsace,18 and the growing power of new worker categories: managerial staff in industry, skilled service workers, and women employed in new business sectors. These worker groups were akin to self-employed workers in terms of their standard of living, but differed in their work status, tax situation and right to social benefits.19 In the bilingual Alsace of the 1920s, housing policies also played an important role in transforming the plural expression ‘classes moyennes’ [middle classes] into the equivalent German singular ‘Mittelstand’ [middle class].20

In 1922 Peirotes created and presided over the City of Strasbourg’s Office of Low-Rent Housing,21 which enjoyed a remit that ‘only rivalled that of Paris and Lille’22 in France. He thus deepened a segmented and hierarchical housing policy, ranging from the elimination of slums to homeownership access. The Ungemach Foundation initiative crowned his strategy: it offered the middle class a highly valued proposition, a ‘garden city’.

The principle of a garden city had been formalized by the British Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928) in a book published in 1898, Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, and had spread throughout Europe and North America.23 As both a utopic and practical solution, the garden city was a response to problems raised by cities’ exploding populations, offering ‘the working-class elite’24 the possibility of accessing what was considered to be the most politically stabilizing form of housing: an individual house surrounded by a garden that, in addition to its contribution to the domestic economy, would channel the worker’s free time into virtuous activities.25

By 1910 the city of Strasbourg had incorporated the garden city into its collective ‘mid-tier’ rental programmes via the Stockfeld ‘suburb-garden’.26 At the end of Peirotes’ term, this garden was joined by the Alexandre Ribot (1930–1932) garden city, and then the Robertsau garden city, launched in 1934.27 Ungemach Gardens was part of this wave of city-supported initiatives, but it differed from the others in one respect: rather than provide access to homeownership, it offered residents rentals. This apparently minor difference might appear to be attributable to a ‘social’ mission, but it actually masks a very particular approach that went hand in hand with an unprecedented regulation of residents’ lives.

The Selection

Ungemach Gardens was not a social housing initiative like the others, although they regularly claimed to be so in order to ensure their continued existence. They were conceived and implemented as an experiment – as a human laboratory seeking to shape the ‘quality of the population’ via a scientific selection of its residents, who contractually committed to meeting childbearing objectives. The initial selection and obligation to procreate were intended to turn the garden city into a ‘breeding ground for elites’, and on a broader scale to test the hypothesis that natural selection mechanisms can be influenced by housing.

The centrepiece of this enterprise was its ranking system for candidate households, built on the bedrock principle of selection. This term should be understood in a specific sense: it linked the scholarly concept of ‘natural selection’ popularized by Darwin with an administrative approach to ‘sorting’ and ‘classifying’ households applying for rentals. The Ungemach Foundation wanted to demonstrate that placing well-selected couples in suitable conditions enables the ‘domination of valued elements in the generation of tomorrow and allows these elements to overtake those of lesser value’.28

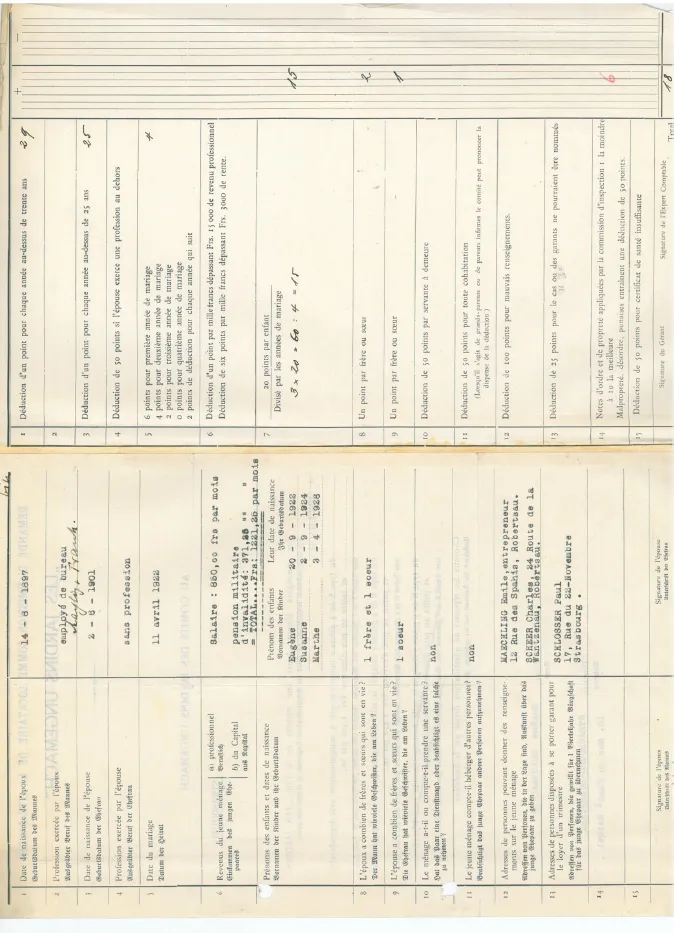

It is worth examining these selection criteria from the perspective of the applicants by comparing Eugène and Marthe Schumacher, who were selected when they first applied in 1927, and Jean and Marie Simon, who experienced three failures before they gained the right to live in the garden city.29 The two couples shared many traits. The women were both born in 1901 and identified themselves as housewives, which was typical of ‘middle-class’ households at the time. Eugène was born in 1897 and was an office worker at the time of application. His annual salary of 14,655 F was double the French average.30

Jean was four years younger and higher up in the services sector. In 1933, when he and his wife finally gained admission, his job as a customs comptroller was bringing in an annual salary of 20,000 F. This relatively high income penalized the Simons by placing them in the upper middle class.

Based on a purportedly scientific approach, the application included fifteen questions and followed a precise methodology to measure what could be called the ‘potential fertility’ of households. First, how many children were they likely to have? The question was approached with an array of data points, starting with the applicants’ ages: husbands had a point removed for each year over thirty years of age; the threshold was lowered to twenty-five years of age for wives. The length of marriage was also taken into account on a sliding scale: young couples were awarded a bonus (six points if they were in their first year of marriage, four for second-year marriages, two for third-year marriages), whereas each year beginning with the fourth one resulted in a two-point deduction.

Figure 1.1. The evaluation of the Schumacher couple. © Municipal Archives in Strasbourg. 99 MW 199.

Each child already brought into the world was awarded twenty points, but this total was divided by the length of marriage to measure what one might call the rhythm of descendant creation. Thus, the three Schumacher children, born within four years of marriage, provided fifteen points to their parents (that is, 3 times 20 divided by 4).

One of the Foundation’s objectives was to minimize the uncertainty linked to the drivers of human procreation: the financial support provided to ‘quality households’ was to be repaid through a virtual guarantee that they would bring...