- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In recent decades, emerging scholarship in the field of girlhood studies has led to a particular interest in dolls as sources of documentary evidence. Deconstructing Dolls pushes the boundaries of doll studies by expanding the definition of dolls, ages of doll players, sites of play, research methods, and application of theory. By utilizing a variety of new approaches, this collected volume seeks to understand the historical and contemporary significance of dolls and girlhood play, particularly as they relate to social meanings in the lives of girls and young women across race, age, time, and culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Deconstructing Dolls by Miriam Forman-Brunell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Dolling Up History

Fictions of Jewish American Girlhood

Lisa Marcus

Introduction

In spring 2009 the American Girl Company introduced Rebecca Rubin, a new Jewish American Girl historical doll (see illustration 1.1). Girls in Los Angeles lined up at 4 a.m. for her launch; New York families could coordinate their visit to meet the new doll with a tour of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. Rebecca Rubin’s debut was exuberantly welcomed by both the mainstream and Jewish press, with The New York Times running a detailed story on 24 May 2009 about her origins and the extensive research that went into creating her. (Apparently, choosing hair color alone took years—it’s “mid-tone brown” with “russet highlights”). The Times reporter subjected the doll to a vetting by Abraham Foxman, of the Anti-Defamation League, who confirmed that “most of the time these things fall into stereotypes which border on the offensive” (a fact evidenced by Foxman’s own collection of Polish wooden dolls, depicting Jewish businessmen counting coins). The Rebecca Rubin doll, he was surprised to find, is a “sensitive” representation of Jewish girlhood (Salkin 2009). Jewish cultural critic Daphne Merkin (2009) wrote in Tablet Magazine about “rush[ing] to order her, despite my advanced years,” and Jewish mothers enthused on the American Girl website (2010) as they ordered dolls and accessories for Hanukkah. One lucky doll recipient gushed, “She is just like me with greenish eyes, brown, curly, shoulder length hair, being Jewish, and loving acting. She could be my twin! I love this doll!.” Another wrote, “This is the best doll ever!!!! She is soooo cute!!! It is also cool that she is Jewish!!! That will be very educational for so many people!!!! She is beautiful!!!!!!” A father, signing in as “Papa Rosenbaum” raves, simply: “Mazel Tov AG!” Real American girls can buy Rebecca for $95. They can also buy a Hanukkah set complete with a shiny menorah made in China, a Sabbath set that includes challah and shabbos candles, a school lunch kit that comes with a plastic bagel and the score for “You’re A Grand Old Flag” (along with the flag itself), and a pricey bedroom ensemble accompanied by two kittens. Rebecca and her many accessories and outfits can be had for the whopping sum of $901.95 before tax.

Illustration 1.1 • Rebecca Rubin Doll and Book. Photo Courtesy of American Girl

Anne Frank, American Girl

So what can a doll tell us about constructions of Jewish American girlhood? I want to contend that the eagerness and hunger with which girls—and their parents and grandparents—embraced Rebecca Rubin as an icon of Jewish American girlhood is significant, because the version of American history for sale in the Rebecca doll and the books that accompany her presents an idealized America in which anti-Semitism and anxieties about Jewish American identity are minimized and glossed over. One might counter, of course, that narratives for children quite appropriately offer gentler, more optimistic visions of history. And, indeed, the Rebecca Rubin books promote an affirmative vision of Jewish American identity that, as the website insists, offers a “girl-sized” view “of significant events that helped shape our country, and … bring history alive for millions of children” (American Girl 2010). Yet the history represented in this work of children’s literature is instructive precisely because it illustrates—and taps into—patterns of ideological desire that resonate more broadly throughout the Jewish American imagination: the desire for fictions of a tolerant and welcoming America, and of a Jewish American identity that fits comfortably within it.

To appreciate the significance of the appearance of a Jewish American Girl in our current moment, the importing and Americanizing of the tragically iconic Jewish girl Anne Frank is instructive, for it reveals many of the same ideological pressures that shape the Rebecca Rubin version of American girlhood. Critics have ably outlined the troubling aspects of Anne Frank’s reception in the United States. Cynthia Ozick (2000) has argued trenchantly that Anne Frank’s story has “been bowdlerized, distorted, transmuted, traduced, reduced; it has been infantilized, Americanized, homogenized, sentimentalized; falsified, kitschified …. A deeply truth-telling work has been turned into an instrument of partial truth, surrogate truth, or anti-truth” (77–78). She cautions that the diary is not “to be taken as a Holocaust document,” and worries that it has “contributed to the subversion of history” (78). Her quarrel is with the popular reduction of Anne into a sunny icon of hope most evident in the 1955 play and 1959 Hollywood film that rely too much on the optimistic spirit of Anne’s oft-quoted statement (taken out of context from the diary) that “in spite of everything” she believes people are basically good at heart. This “Hollywood Anne,” as Tim Cole (1999) has called her, is quintessentially hopeful; she “comforts us that people are still basically pretty decent, thus silencing any challenge that the Holocaust might make to our naïve optimism in human potential” (77). As Bruno Bettelheim (2000) insists, the immense popularity of an idealized Anne stems from audiences’ desire for a history that acknowledges the horror of genocide only to release us from the burden of its legacy:

Her seeming survival through her moving statement about the goodness of men releases us effectively of the need to cope with the problems Auschwitz presents. That is why we are so relieved by her statement. It explains why millions loved the play and movie, because while it confronts us with the fact that Auschwitz existed, it encourages us at the same time to ignore any of its implications. If all men are good at heart, there never really was an Auschwitz. (189)

Indeed, such audience desires directly shaped the construction of a “Hollywood Anne.” As Ellen Feldman (2005) reports,

our need for a happy Anne, despite her profoundly unhappy ending, runs so deep that when preview audiences saw the last scenes of the original cut of the movie, which showed Anne at Auschwitz, they scrawled outrage on their opinion cards. This was not the Anne they knew. (n.p.)

That scene was scrapped and replaced with the hopeful voiceover.

One of the reasons Anne Frank’s narrative is so popular in the American imagination, these critics challenge, is that “Hollywood Anne” doesn’t really die, at least not in front of us. Lawrence Langer (2000a), arguing that “upbeat endings seem to be de rigueur for the American imagination which traditionally buries its tragedies and lets them fester in the shadow of forgetfulness” (200), suggests that “one appeal of the diary is that it shelters both students and teachers from the worst, to say nothing of the unthinkable, making them feel they have encountered the Holocaust without being threatened by intolerable images” (Langer 2000b: 204). Martha Ravits (1997) adds, “It has served like Perseus’s shield as a polished mirror in which a viewer can behold the face of atrocity without being paralyzed by it” (18).

At stake in such critiques are important issues about the uses to which historical memory (or amnesia) are put. The Americanization of Anne Frank feeds a desire for a flattering and exceptionalist American self-image—one of benevolence, innocence, and affirmation of diversity. Mark Anderson (2007) writes that while child narratives such as Anne Frank’s “had the undeniable merit of winning the hearts of mainstream, non-Jewish audiences in the 1950s and 60s … they also set the terms for an Americanization of Holocaust memory that privatized and sentimentalized the historical event [and] … they also depoliticized and sacralized the Holocaust, filed off the rough edges of the Jewish protagonists, and sought reconciliation rather than confrontation with the gentile world” (19). I share his worry that too often Anne Frank’s story is embraced as a vehicle for “teaching tolerance” and that this is frequently based on what he calls “no cost multiculturalism,” which “provides the illusion of diversity without requiring that anything or anyone actually change” and “goes hand in hand with an almost complete lack of historical perspective” (17). Startling, then, is the fact reported by Francine Prose (2009) that while 50% of American schoolchildren had studied Anne Frank in a classroom assignment in 2004, 25% of American teenagers in another study could not correctly identify Hitler (253–254).

That Anne Frank continues to be symbolically important to Americans can be seen in the plan, as reported in the New York Daily News, 17 April 2009, to plant at Ground Zero, in commemoration of the 9/11 attacks, a sapling from the tree that Anne gazed at from her hidden attic in Amsterdam. If such Americanization of Anne Frank weren’t troubling enough, her transformation into an American girl was almost completed in 2004 when a Long Island congressman petitioned for her honorary U.S. citizenship. Though the petition was not successful, Islip Town Council member Christopher Boykin regards “America as Anne Frank’s natural home. Who better than this country to afford Anne Frank citizenship? It’s been a place that has been safe for the Jews literally since day one” (Clyne 2004). While history proves otherwise, it is compelling that an elected official would hold to such a romantic view of Jewish American history. But that view is matched by many, including the American Girl Company.

History for Sale

Sue Fishkoff (2009), writing for The Jerusalem Post, asserts in her review of the Rebecca Rubin doll, “Jews love history, especially their own.” She goes on to suggest that

Jewish parents hip to the American Girl formula of nicely-made dolls and well-written books about the period of American history they represent, wanted a piece of their own people’s story to give their daughters. “This is our history, right here in this doll,” says author Meredith Jacobs of Rockville, Md., host of The Modern Jewish Mom on The Jewish Channel. (n.p.)

Another mother, writing in to the American Girl website (2010), gushes: “I love that when you buy an AG historical doll—you are also buying a bit of the past!” I want to think here about what it means to “buy a piece of the past,” particularly a piece of Jewish American history that has been sanitized and reconstructed in frilly white pajamas with two pet kittens. All of the American Girl historical dolls are created with a boxed-set of six books that lay out the girl’s story in a particular year (always ending in 4) in American history. The books are researched, and include historical appendices that add authenticity to the fictional tales offered within the covers. Rebecca Rubin’s story is set in 1914, a shrewd choice that was evidently vetted with Focus Groups and historical research initiated by the American Girl marketing department. Setting the fictional Rebecca, who is nine years old in the stories, in 1914 strategically allows the American Girl Company to present an upbeat Jewish American history that highlights “assimilation, blending in and becoming American,” as the senior vice president for marketing, Shawn Dennis reports in the Times article (Salkin 2009). 1914 is safely past the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire (1911), prior to the lynching of Leo Frank in Atlanta in 1915, and well in advance of the drastic restrictions of 1924 that effectively choked off immigration from Eastern Europe, as nativist legislators sought to control the racial and ethnic make-up of the United States, sometimes explicitly stating that their efforts would curb Jewish migration. It also falls before the implementation of quotas limiting Jewish enrollment at elite universities, and importantly, it allows for a pre-Holocaust Jewish America unscarred by the Nazi genocide.

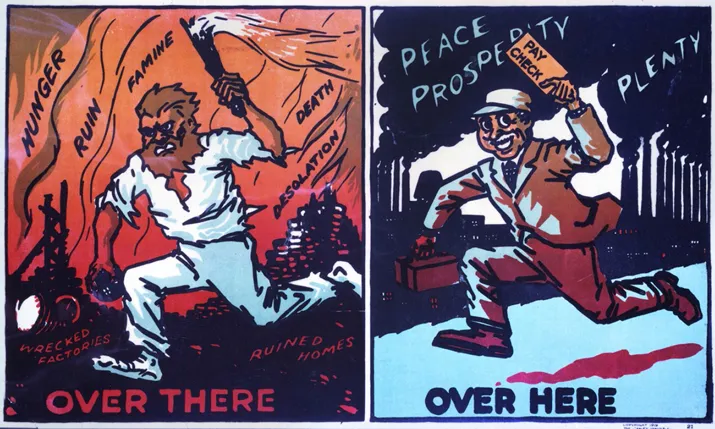

Housed within the confines of this carefully selected historical moment, the Rebecca stories construct an idealized, triumphalist immigrant narrative of a welcoming America and a Jewish American girl whose potentially conflicting identities are happily fused and only minimally challenged. In the first book, the question of naming is easily resolved when cousin Moyshe Shereshevsky announces, “it’s no more Moyshe Shereshevsky… I am Max Shepherd, if you please … an American name for an American actor” (Dembar Greene 2009a :8). While “Bubbie” grumbles that “you don’t change a name like a dirty shirt,” (8) her old world view is swept aside as Max—seemingly with no effort—becomes a rich movie actor and contributes his first paycheck to help finance the passage for Rebecca’s cousin’s family to flee the Pogroms of Russia just in time to avoid conscription in the war. Indeed, the Historical Notes to the Rebecca series feature a poster (on display at Ellis Island), which contrasts the anti-Semitic old world to the welcoming new world (see illustration 1.2).

When the cousin’s family arrives, in the second book in the series, Max and Rebecca serenade the new immigrants with a loud rendition of “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” emphasizing “free” and “brave” in the lines, “You’re the land I love, the home of the free and the brave …” (Dembar Greene 2009b: 5). Even Bubbie nods in time with the music while “Grandpa” (too assimilated, we assume, to be called Zadie) taps his foot. The thick patriotism of this narrative offers a syrupy version of easy assimilation highlighted when newly arrived cousin Ana is featured in a duet with Rebecca singing George M. Cohan’s lyrics at a school assembly to celebrate the arrival of a new flag for display. In the auditorium, under the golden lettering of the “names of famous Americans: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln” (66), the two Jewish girls belt out their patriotic song, pledging allegiance to a welcoming America in which new immigrants quickly lose their accents, assimilate, and move out of the tenements and into the American dream. This matters to American Girl marketers, because in order to sell this “bit of history” to moms like those cited above, Rebecca can’t live in a tenement like the one Lewis W. Hine photographed in 1910 (see illustration 1.3). Her bedroom set has to be cute enough for little girls to want to play house with (see illustration 1.4), and should include matching pajamas for doll and girl.

Illustration 1.2 • 1919 poster contrasting old world and American possibility. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress and the Statue of Liberty National Monument

To be sure, these books chronicle Rebecca’s struggles as well, but these are limited to anxieties that are easily resolved. She manifests just enough nascent feminism to appeal to contemporary mothers, evidenced best when she grumbles about the gender-segregated synagogue in which her brother is bar mitzvahed. Scolded for her kvetching, Rebecca is reminded by Bubbie that, “to be a good Jewish wife and mother … you must keep the house kosher and observe the Sabbath every week. The men will do the Torah reading” (Dembar Greene 2009c: 6). She later performs a daring Coney Island rescue of her cousin stuck on a broken ferris wheel, asserting her girl power without really challenging the patriarchal status quo.

Her chutzpah resurfaces in the final, and most politically radical, of the books when Rebecca becomes a veritable voice for the union after her uncle and cousin strike to protest the miserable conditions of garment workers. As Rebecc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Interrogating the Meanings of Dolls: New Directions in Doll Studies

- Chapter 1 Dolling Up History: Fictions of Jewish American Girlhood

- Chapter 2 “A Story, Exemplified in a Series of Figures”: Paper Doll versus Moral Tale in the Nineteenth Century

- Chapter 3 From American Girls into American Women: A Discussion of American Girl Doll Nostalgia

- Chapter 4 Barbie versus Modulor: Ideal Bodies, Buildings, and Typical Users

- Chapter 5 Handmade Identities: Girls, Dolls and DIY

- Chapter 6 An Afternoon of Productive Play with Problematic Dolls: The Importance of Foregrounding Children’s Voices in Research

- Chapter 7 Some Assembly Required: Black Barbie and the Fabrication of Nicki Minaj

- Chapter 8 Black Girls and Dolls Navigating Race, Class, and Gender in Toronto

- Index