![]()

The Wizard of Oz

The Story

Sunday mornings were always a special time for L. Frank Baum because he knew the children would gather around him to hear a story. But this Sunday, he first had to finish reading his Chicago Tribune because the news was important: Admiral Dewey had accomplished a great military victory in Manila and it would be a date to remember: May 7, 1898. When he finally finished reading the paper, he put it aside and let the children into the den. In addition to his son, Frank Jr., and his three brothers, there were three neighborhood children in the group. Some sat in chairs, others spread out on the floor, all waiting for the start of another tale. It had been that way for as many Sundays as they could remember, and they were seldom disappointed.

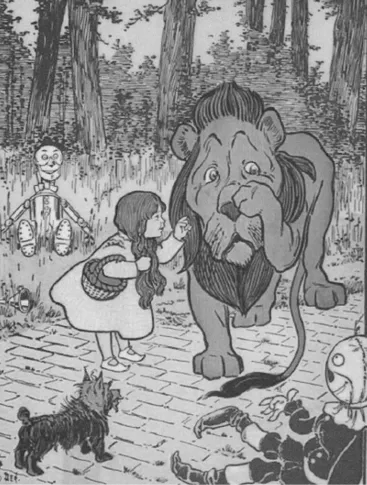

Before he began, Baum picked up a pencil and put his writing pad on his knee so he could make notes as he talked. He leaned back in his big leather upholstered chair and began— not quite where he had left off—but close enough so that no one objected. It was a story he had been telling and embellishing for a long time now, a story about a little girl who found herself in a strange land, accompanied by two men, one made of straw and another made of tin. They were searching for an emerald city where everything was green, even the sky, and where hope resided. There were always obstacles on the way—witches and flying monkeys and impenetrable forests. Sometimes there were poisonous flowers, and once there was a cow that gave ice cream. Sometimes the name of the little girl changed, but today it was Dorothy, and she had a little dog named Toto, and they were lost in a strange fairyland.

The children would often interrupt to ask a question. What was the name of the good witch? When was Dorothy going to be home again? This morning, one of them asked a question several of them had wondered about: What was the name of this strange land? Baum didn’t have a quick answer, but then he happened to glance over at his filing cabinet. The top drawer was labeled “A-N.” The bottom cabinet said “O-Z.” “Why,” he said, “this story took place in a land called ‘Oz’!”

Frank Baum had been writing and telling stories most of his life. As a youngster growing up in a small village outside Syracuse, New York, he was known as a daydreamer—always reading, writing poetry, and telling tall tales to his friends. He never lacked for an audience: He was the seventh of nine children in a prosperous Methodist family. When he was barely a teenager, his father gave him a small printing press, and he began publishing his own little newspaper for which he wrote articles and stories. Baum loved the theater, never missing a chance to see a traveling show or an amateur entertainment.

Baum also possessed a strong entrepreneurial streak. At the age of twenty, he began breeding fancy poultry—and he then wrote a book about the experience. He would later be a retail shop owner, a traveling salesman, and a shop window designer—and, of course, he wrote books about those experiences as well. He also started a minor league baseball team—which resulted in neither profits nor a book.

While Baum had the entrepreneurial spirit, he unfortunately did not have business acumen. He repeatedly failed in business and, because he was now married and raising a family, he decided he should try to make his way in literature and in the theater. He had already written a number of plays and had founded his own small theatrical production company. Like so many of his other projects, they were financial failures. In 1897, he wrote and published a collection of Mother Goose stories, using his proper name, L. Frank Baum. The collection was illustrated by an aspiring artist named Maxfield Parrish, and the book was successful enough that Baum decided to devote himself full-time to writing.

The Road to Oz

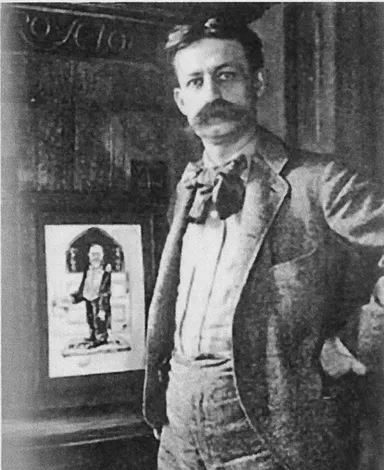

A mutual friend introduced Baum to a resident artist named William Wallace Denslow, who was already an established figure in the art world of Chicago. Denslow had a reputation as a newspaper artist and as a designer of posters and of book covers. He had a knack for portraying whimsical and fantastical subjects. Baum and Denslow became fast friends and it was only a matter of time before they decided to collaborate. Baum wanted to capitalize on the success of his Mother Goose book with a series of tales called Father Goose. The two of them worked on the book together, with Baum’s prose inspiring Denslow and Denslow’s drawings inspiring Baum. The combination produced a beautiful and enchanting book, and it also produced a lasting partnership between the writer and the artist in which they agreed to share both credit and royalties. Father Goose was even more successful than its predecessor. Published in 1899, it sold more than twenty-five thousand copies before the year was out. The partnership was off to a great start.

By this time, Baum had developed a custom of entertaining his children and their friends with his fanciful tales. This served two purposes. Baum loved to entertain and to be the center of attention, and he found his gatherings with young people fulfilling and satisfying. But it also permitted Baum to see what kind of stories they most enjoyed. He learned that they were not keen on stories that pointed up a moral or taught a lesson. He saw that their minds wandered off and their attention flagged at the first hint of romance or of tales about princes and princesses. They liked child heroes, unexpected happenings, scary situations, and magical escapes. Over time, it became obvious to Baum that the children were especially fond of the story he had created and embellished about the little girl Dorothy who found herself in a strange and scary world populated by witches, a tin woodsman, and a scarecrow. He invented a green city for them and a wizard. He knew from their interest and their reactions that he was onto something good. He decided to ask his friend and partner William Denslow to see what he could contribute to the story, which he now called “The Emerald City.”

In the summer of 1899, Denslow joined Baum in his writer’s den and Baum outlined for him the story that he had been telling the children off and on for two years. Baum leaned back in his leather chair as he talked and puffed on his cigar as he wrote on his pad with a soft lead pencil. While he talked, Denslow sketched on his own pad, puffing on his pipe. Over the days that followed, through the smoke and conversation, the characters came to life in word and picture—Dorothy, the Good Witch of the North, the Wicked Witch of the West, the dog Toto, the Tin Woodsman, the Scarecrow, and the Wizard. Then Denslow drew something new: a Cowardly Lion. Baum loved it and they put him into the story. Baum wrote in such a careful hand that the publisher could set type from it. Denslow’s drawings showed comic animals with human features and were executed with distinctive color tones. Baum had been calling his unfolding story “The Emerald City,” but now he decided that title was not sufficiently descriptive of the expanded novel, so he changed it to From Kansas to Fairyland.

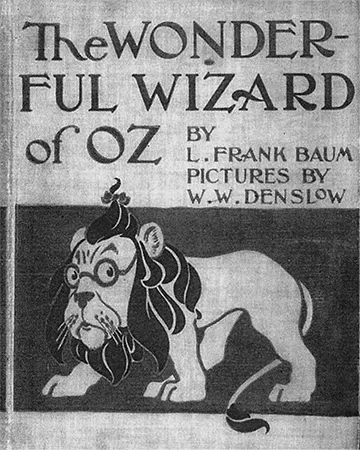

The book had no problem finding a publisher. George H. Hill, who had published their Father Goose book, paid a $500 advance to both Baum and Denslow and agreed to pay 12 percent royalty payments on a list price of $1.50 per copy. Hill also told Baum he didn’t like the title From Kansas to Fairyland. Baum countered with The Land of Oz, and the book was copyrighted under that title. However, neither Denslow nor Hill were happy with the new title, so Baum came up with one more try. In September of 1900, the book that they finally published was entitled The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

The book was an immediate success. It was reviewed by more than two hundred newspapers and periodicals. Superlatives danced through almost every review: “delightful humor and rare philosophy found on every page”…“Dorothy’s companions are both real and wonderful”…“new features and ideals of fairy life”…“ingeniously woven out of commonplace material”…“philosophy and satire that will furnish amusement to the adult and cause the juvenile to think some new and healthy thoughts.”

As Christmastime approached, the Baum household was short of funds, so Baum was asked by his wife to go to his publisher’s office to see if he could possibly collect a hundred or so dollars in royalties. Reluctantly, he did as he was asked. He came home and handed his wife the sealed envelope he had been given. When she opened the envelope and pulled out the enclosure, she gasped in astonishment. Together, they looked at it in disbelief. It was a check for $3,432.64.

Before the next year was out, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz had sold more than thirty-seven thousand copies and had become the best-selling children’s book in America.

Baum took advantage of the great success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by indulging his great love of the theater. He mounted a stage version of the book using, for the first time, th...