- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The official publication of the American Bach Society, Bach Perspectives pioneers new areas of research into the life, times, and music of the master composer. In Volume 10 of the series, Matthew Dirst edits a collection of groundbreaking essays exploring various aspects of Bach's organ-related activities. Lynn Edwards Butler reconsiders Bach's report on Johann Scheibe's organ at St. Paul's Church in Leipzig. Robin Leaver clarifies the likely provenance and purpose of a collection of chorale harmonizations copied in Dresden. George Stauffer investigates the ways various independent trio movements served Bach as an artist and teacher. In separate contributions, Christoph Wolff and Gregory Butler seek the origins of concerted Bach cantata movements spotlighting the organ and propose family trees of both parent works and offspring. Finally, Matthew Cron provides a broad cultural frame for such pieces and notes how their components engage in a larger discourse about the German Baroque organ's intimation of heaven.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bach Perspectives, Volume 10 by Matthew Dirst in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Music from Heaven

An Eighteenth-Century Context for Cantatas with Obbligato Organ

Of the almost two hundred surviving church cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach, eighteen contain movements where the organist steps out of his normal role of continuo player and becomes a concertist. Modern scholarship has considered such compositions primarily from two perspectives: a historiographical perspective places them in the larger context of the history of the keyboard concerto, while a compositional perspective considers them as examples of the arrangement and reworking of previous musical material. The following study examines these works from the perspective of an original listener (in other words, a member of the congregation) to describe how a particular yet widespread way of thinking about the organ created a fruitful context for this new type of cantata in the early eighteenth century.

No member of Bach's Leipzig congregation would have had the historical hindsight to link concerted organ movements in church to the emerging keyboard concerto. Even those who might have heard Bach's harpsichord concertos at Zimmermann's coffeehouse in the 1730s may not have remembered hearing organ versions of a half-dozen movements in a group of cantatas from 1726. While some Leipzigers may have recognized concerto form in these six movements, Bach's extant cantatas contain twenty-seven other movements, mostly arias, that use the organ in a non-concerted manner. In these, the organ functions in the same manner as a solo flute, oboe, or violin in arias from other cantatas—that is, as an instrumental obbligato. Nor would eighteenth-century listeners have had the wide range of assocations for the organ as we do—from the concert hall to the ball park. Because Bach's contemporaries encountered the organ primarily within a church context, their understanding of the instrument would have relied on its striking visual impact, its use in worship (especially in hymn singing), and on what was said about it in devotionals, sermons, writings on music, and in cantata texts, especially those in which the organ is featured prominently. The one constant in all these various media was a strong association of the organ with Heaven: this instrument, above all others, prepares one for service in the heavenly choir while providing a source of solace and joy on earth.

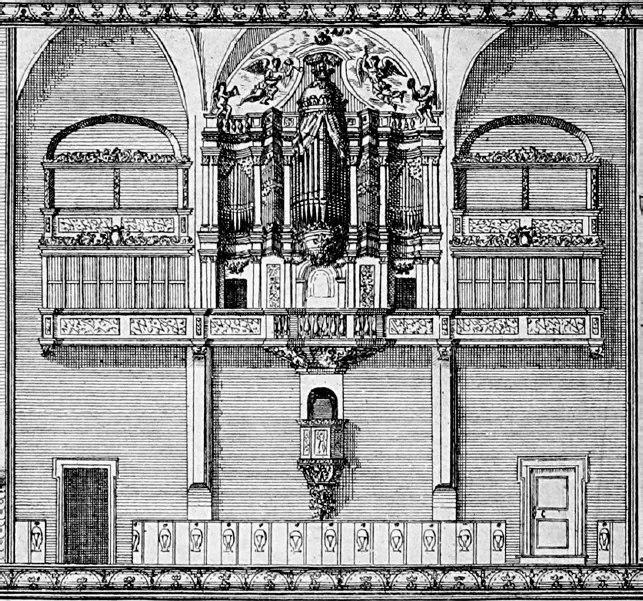

During the Baroque Age the decoration of organs with the symbols of Heaven—angels, clouds, sun, and stars—provided a powerful visual context for the instrument.1 The most frequent symbol of Heaven found on these instruments is the angel, which can be depicted in a variety of ways, from carved busts to full-body statues or child-like putti.2 Angels of judgement (typically with trumpets) are also common, as are angel musicians of all sorts playing violins, trombones, harps, even timpani.3 Angels and clouds were also frequently painted on organ doors or on walls behind organs, reminding the faithful that even when not in use, these instruments were somehow part of Heaven on earth. One particularly fine example of this kind of decoration can be found in an organ that was familiar to both Bach and Georg Philipp Telemann. An engraving of the Donat organ of the New Church in Leipzig, as rebuilt by Johann Scheibe in 1722, depicts two small angels on the sides of the top of the organ case and two large angels in flight amid clouds painted on the vaulted wall behind the organ (see plate 1[OBH, 57]).4 Seen from the main floor of the church, the organ appeared as if in Heaven accompanied by angels. Explicit or implicit connections between the Psalms and Baroque organ decoration were common, as can be seen in a well-known engraving of the 1714 Silbermann organ in Freiberg Cathedral.5 This engraving depicts a performance of concerted music with the new organ, whose case includes two small angels at the very top and two trumpeting angels surrounding the Oberwerk. On the sides of the Brustwerk are an angel playing an organ and another playing drums, both seated on heavenly clouds.6

Plate 1. Engraving of the Donat organ of the New Church in Leipzig, rebuilt by Johann Scheibe in 1722

Other celestial symbols found on organs of this time include the sun and stars. The former is most prominently represented on the Casparini organ (the so-called “Sun Organ”) in the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Görlitz as well as the Wagner organs in St. Mary Church, Berlin, and the Garrison Church in Potsdam, which also had animated angels that were activated by drawknobs for fanfaring and drumming angels, respectively.7 The Casparini organ had revolving suns, angels, and birds, all of which played specific pitches.8 Such an aural reminder of the celestial object is also found in the Cymbelstern stops present on most of the organs associated with Bach, including the Stertzing organ in St. George Church in Eisenach, which had two Cymbelstern whose stars and bells could be operated separately,9 and also on organs in every city where Bach held a post. The constant sound of bells was a reminder of Psalm 150's exhortation to praise God with the sound of cymbals, a sentiment echoed in the final verse of the familiar Christmas hymn In dulci jubilo: “Where is joy, nowhere more than there? There the angels sing new songs, and there the bells ring in the King's court; O that we were there!”10 The Vogelgesang, a common “toy stop” on German instruments of this time, conjured similar associations for generations of listeners.11 While one might regard a stop that imitates warbling birds as a mere novelty, its spiritual significance is discussed in organ dedication sermons, one of which claims that the sound of the Vogelgesang causes one to “take wing, rising from the earthly lot, and intone the heavenly music: Gloria in Excelsis Deo! Glory be to God in the highest!”12 Additional observations from dedication sermons will concern us presently.

The physical location of the organ also reinforced its status as a heavenly instrument: even in relatively small churches with modest organs, placement was usually as high as possible, on a second or even a third balcony. With the tools and machinery available to organ builders of this time, such great elevation required significant amounts of labor, logistics, and engineering prowess; yet the earliest organs that Bach encountered were situated in this manner: the Stertzing organ in St. George Church in Eisenach and the Wender organ in the New Church in Arnstadt, for instance.13 The organ of the Weimar Schloßkapelle is perhaps the most extreme example from Bach's career of a heavenward organ placement: rather than reaching toward the ceiling of the church, this organ was placed above it.14 By no surprise, the ceiling was painted blue and the church was known as “Weg zur Himmelsburg” [Path to the Fortress of Heaven]. The upper ceiling above this organ was painted with clouds and angels, and though the Weimar court could hardly have seen the instrument well, hearing a chorale like “Vom Himmel hoch” on this instrument must have been especially meaningful.15 Bach's Mülhausen congregation looked up to a three-manual organ that had a large winged angel at the very top, a number of smaller angels, a twelve-bell Cymbelstern and a 32' Untersatz, all of which contributed to its perception as a musical representation of Heaven.16 The Leipzig instruments, outfitted with similar accoutrements, doubtless inspired similar reverence.17 The smaller organ in St. Thomas Church, by virtue of its “swallow's nest” position high above the floor of the church and its decoration, was the most celestial of the Leipzig instruments: both of the winged doors from the original 1489 instrument were inscribed “Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus // Domine Deus Zebaoth,” words which, as Isaiah reports, the six-winged Seraphim repeated over and over.18 Bach seems to have understood this organ's iconic status from the outset of his Leipzig tenure: he likely used it at his first Christmas service, for the interpolations in the Magnificat in E-flat (BWV 243a), which begin with the opening verse of the chorale Vom Himmel hoch: “From Heaven above to earth I come, to bring good news to every home.”19

A popular devotional book in Bach's library, written by pastor and theologian Heinrich Müller (1631–1675),20 made equally explicit claims for the organ's heavenly pedigree. Müller's Göttlicher Liebes-Flamme (Divine Flame of Love), first printed in 1659,21 contains an illustration that graphically represents Ephesians 5:19, a passage where Paul exhorts, “Sing and play to the Lord in your hearts,” with singers and stringed instruments making figural music around an organ (see plate 2).22 This emblem, from the end of chapter 25 (“On the salvation of the Righteous”), features, above the heart, angels who are also making music; and in the middle of this heavenly choir there is a parallel organ plus a harp.23 The caption reads:

From my heart, I praise you, because of you and your goodness.

O wonderfully great God, delight my mind,

The heavens praise you, I have Heaven here on earth when I praise you

—thus one becomes like an angel.

O wonderfully great God, delight my mind,

The heavens praise you, I have Heaven here on earth when I praise you

—thus one becomes like an angel.

Plate 2. Emblem from Heinrich Müller, Göttlicher Liebes-Flamme

Making clear the organ's role in both earthly and heavenly musicmaking, the emblem illustrates the relationship between the faithful and the musicians who perform on their behalf: even those who neither sing nor play an instrument nevertheless experience the music in their hearts. The attached poem clarifies the organ's role not only in representing Heaven but in the way that figural music prepares the righteous for eternal life.24

Among German writers such ideas were a commonplace of devotional as well as theoretical literature. Michael Praetorius, for example, maintains in the second volume of his Syntagma Musicum (1618) that “we must all, as servants of the Lord, make music…and in a steady constant Cantorei…let us learn the art on earth, which we will use in Heaven.”25 Or Johann Friderich Walther, organist of the Garnison-Kirche in Berlin, who concludes his lengthy description of the newly-built 1726 Joachim Wagner organ as follows:

Yes, may great God grant, as we unite all our voices with the sweet sound of the organ, that some day in blessed eternity we may be worthy to raise our voices with all the holy angels and chosen ones in a sacred and beautiful harmony, and to praise and glorify without end the Triune God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.26

Prefaces to hymnals and chorale books, the perfect place to reinforce this point to a wide audience, likewise admonished the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Bach's Report on Johann Scheibe's Organ for St Paul's Church, Leipzig: A Reassessment

- Bach's Choral-Buch? The Significance of a Manuscript in the Sibley Library

- Miscellaneous Organ Trios from Bach's Leipzig Workshop

- Did J. S. Bach Write Organ Concertos? Apropos the Prehistory of Cantata Movements with Obbligato Organ

- The Choir Loft as Chamber: Concerted Movements by Bach from the Mid- to Late 1720s

- Music from Heaven: An Eighteenth-Century Context for Cantatas with Obbligato Organ

- Contributors

- General Index

- Index of Bach's Works