eBook - ePub

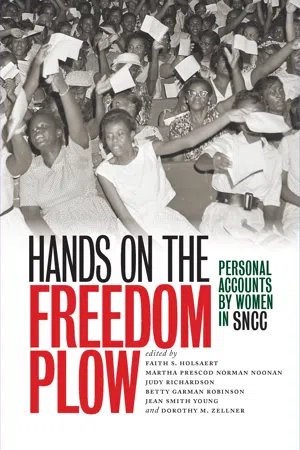

Hands on the Freedom Plow

Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hands on the Freedom Plow

Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC

About this book

In Hands on the Freedom Plow, fifty-two women--northern and southern, young and old, urban and rural, black, white, and Latina--share their courageous personal stories of working for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement.

The testimonies gathered here present a sweeping personal history of SNCC: early sit-ins, voter registration campaigns, and freedom rides; the 1963 March on Washington, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, and the movements in Alabama and Maryland; and Black Power and antiwar activism. Since the women spent time in the Deep South, many also describe risking their lives through beatings and arrests and witnessing unspeakable violence. These intense stories depict women, many very young, dealing with extreme fear and finding the remarkable strength to survive.

The women in SNCC acquired new skills, experienced personal growth, sustained one another, and even had fun in the midst of serious struggle. Readers are privy to their analyses of the Movement, its tactics, strategies, and underlying philosophies. The contributors revisit central debates of the struggle including the role of nonviolence and self-defense, the role of white people in a black-led movement, and the role of women within the Movement and the society at large.

Each story reveals how the struggle for social change was formed, supported, and maintained by the women who kept their "hands on the freedom plow." As the editors write in the introduction, "Though the voices are different, they all tell the same story--of women bursting out of constraints, leaving school, leaving their hometowns, meeting new people, talking into the night, laughing, going to jail, being afraid, teaching in Freedom Schools, working in the field, dancing at the Elks Hall, working the WATS line to relay horror story after horror story, telling the press, telling the story, telling the word. And making a difference in this world."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hands on the Freedom Plow by Faith S. Holsaert, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, Dorothy M. Zellner, Faith S. Holsaert,Martha Prescod Norman Noonan,Judy Richardson,Betty Garman Robinson,Jean Smith Young,Dorothy M. Zellner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2010Print ISBN

9780252078880, 9780252035579eBook ISBN

9780252098871PART 1

Fighting for My Rights

One SNCC Woman’s Experience, 1961–1964

Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons’s account spans several years of SNCC history and incorporates themes found in the remaining fifty-four contributions. Her story introduces memories of courage, conflict, and fear and expresses the hope and commitment of every woman who chose to act on her conviction that equality and freedom were worth any price.

Steeped in a family history that included recollections of slavery, Simmons lived a comfortable and protected life in her hometown of Memphis, Tennessee, until, as a high school student, she left the black community to look for work. Her quest to understand and protest racism brought her into the sit-in movement and later to the front lines of struggle in the Mississippi Movement. Here she chronicles her personal growth from a gradual and somewhat timid entrance into activism to becoming a self-assured project director.

“Fighting for My Rights” is the title of a freedom song written by Freedom Singer Chuck Neblett in a Charleston, Missouri, jailhouse and set to the Ray Charles tune “Lonely Avenue.” The song begins, “Well, I’m tired of segregation / And I want my equal rights / Respect and education / Total desegregation” and is followed by the chorus, “That’s why I’m fighting for my rights / Fighting for my rights / Fighting for my rights.”

From Little Memphis Girl to Mississippi Amazon

A college student is torn between meeting her high academic goals and her growing commitment to the Movement. Her activism is met with fierce opposition from black college administrators and her family.

The Early Years

My paternal grandmother, Rhoda Bell Temple-Robinson-Hudson-Douglas (she was married three times and outlived them all), who reared me from the age of three (she was “Mama” to me), told me a lot about the ways of the world for a black girl-child in the heart of the Deep South. My grandmother had been raised by her grandmother, who spent her youth and early adulthood in slavery. The product of a white “master” and an enslaved African American mother, Grandma Lucy was blonde and blue-eyed (hard to believe if you saw my grandmother or me). Grandma Lucy hated the color of her skin because of all the suffering it had caused her. When she was eleven or twelve years old, her slave master/father gave her as a wedding gift to her half “all white” sister. This sister hated her immensely, presumably because she knew that her father was Lucy’s father, too. The punishments the new “mistress” meted out to her half-sister for any infractions of her draconian codes included lashes with a buggy whip and, most cruel of all, the insertion of long darning needles between Grandma Lucy’s fingernails and nail beds while my great-great-grandmother bled profusely and begged for mercy. Grandma Lucy told my grandmother the stories of slavery as she grew up. My grandmother then told them to me. I have told them to my daughter, Aishah Shahidah Simmons (may the circle be unbroken!).

Mama was a great storyteller. I learned about the harsh realities she had faced under the sharecropping system, trying to eke out a meager living from the soil from year to year in the face of harrowing racism and an economic system stacked against the sharecropper. She had spent all of her early life on different farms in Arkansas, and although the conditions in each place were none too good, she said she always gave thanks for not living in Mississippi, which was the worst “hell hole” in the whole wide world for black folks.

I can remember being terrified by the stories she told about Negroes still living at that time under a virtual form of slavery in Mississippi. She knew people who had recently escaped from Mississippi plantations where they had been held for years at gunpoint because of their so-called indebtedness to their white landowners. She said she thanked God every day that she had not had to set foot into the state of Mississippi, and she warned me never to land there if I knew what was good for me. Of course I promised myself that I would never, ever go there! Memphis was bad enough; I certainly didn’t want it any worse.

For the most part, growing up was joyful. I lived happily in my all-black world, surrounded by a loving family and wonderful teachers and church members; they showered me with tender care, support, and encouragement to reach the highest goals that I could imagine, in spite of the obstacles of race and gender. Mama was a happy person by nature, kind and loving and full of the joy of life. I guess our temperaments and personalities meshed well, and life with my grandparents was a happy one. Although my mother (Juanita Cranford-Robinson-Watson) and father (Major Lewis Robinson) were separated when I was three and a half, they were loving, affirming, and actively involved in my life. After my parents’ breakup, Mama asked if she could keep me, since my mother had to return to work full-time. I did spend many weekends with my sweet mother, who was like a big sister to me, and my father lived in the house off and on with my grandparents and me for most of my growing up. Though he wasn’t one to express much affection verbally, he clearly loved me, and as I grew up to be a leader at school and at church, he was visibly proud.

My aunts Jessie (Jessie Neal Hudson) and Ollie Bee (Ollie B. Smith) both took great interest in me and encouraged me to excel. Both were strong women who took their destinies into their own hands and carved out rich and wonderful lives. My aunt Jessie was especially attractive, lived in Chicago, and boasted a wardrobe and colognes that I thought only movie stars owned. With her high school diploma in hand, she migrated to Chicago, as so many Memphians did, and pushed her way into the white preserve of retail window design. On her biyearly treks home to Memphis, she regaled me with stories of her life in the Windy City. She made my whole community come to life when she came to town. She was all of my friends’ “Aunt Jessie” too. She brought many of them presents and baked for everyone. There was music and dancing in the house when she came. She taught me how to dance. And the clothes that she brought or sent me twice a year made my eyes bug out. Bold, audacious, daring, and a pioneering spirit are terms that best describe her. It was through her that I learned that while the North did offer more opportunities to black people than did the South, it was still no Promised Land!

I was blessed with many excellent women role models: there was Miss Willa McWilliams-Walker—my second-grade teacher—who was the first black person to run for the Memphis school board. At my church there were Dr. Clara Brawner, the first black woman doctor I ever saw; her sister Alpha Brawner, a world-renowned opera singer; and Ophelia Little, another internationally known opera singer. There were so many good teachers at my school and mentors at my church home who made special efforts to help me develop my leadership potential. By and large it was these womenfolk who made indelible impressions on me during my developing years. They told me constantly that I should reach for the stars. I studied hard, played hard, did well in school, and set my sights upon attaining a full tuition scholarship from either Howard University or Spelman College, two of the most prestigious historically black colleges in the United States.

Yes, I was subjected to the daily indignities that all black people were exposed to. But for the most part, these things were the gray background to the Technicolor life that I was busily leading at the time. For the most part it only minimally intruded upon my happy, busy, event-filled, and purposeful life.

The Realization

At the end of my junior year in high school, it was clear that I had to get a job and save money for college. A number of my peers, particularly the boys, had begun working during the summers long before me. Many of them worked in nearby cotton fields, being paid meagerly for their backbreaking efforts. I had been spared this exhausting work by my grandmother, who said, “I have picked enough cotton for the both of us.” Fortunately, our family could afford to live without my adding to the family’s income, since both my father and grandfather were working. My granddad, Henry “Lev” Douglas, worked at a whiskey distillery that even unionized. He was proud to be a union man.

For some reason I got it into my head that I wanted a “nice” job (read, white folks–type job) working in an office or in a department store. I answered several want ads, only to be told by the irate and anxious clerks that this was not a job for a “colored girl.” I began to feel a bit depressed about securing a good summer job. One day in early June, I was again rebuffed. It was hot, and the air was so thick and humid that you could have cut it with a knife. I was standing outside a commercial establishment wondering if I should answer some of the other ads or just call it quits for the day. Quite suddenly a violent thunderstorm blew up, and before I could collect myself, I was caught in torrential rains with thunder and lightning flashing all around. I was quite disturbed about being caught out in the open in a thunderstorm with no shelter. As I looked around at the glass-and-concrete buildings and at the white people standing in the windows looking out at the storm—and me in it—I was seized by the feeling of being stranded in an alien land. I was in my homeland, yet somehow I did not know the place. I stood there on the street, soaked to my skin, with thunder and lightning playing all around. I began to cry as I looked at all the cold buildings with their white inhabitants surrounding me. There was no shelter for me in this storm. I felt foreign and alone. For the first time, I think I realized what it meant to be black in the American South. Mama and all the loving ones who had shielded me from the harsh realities were not there. This was the real South for a black girl. I was afraid and angry. For the first time, I felt hatred for the white South and all the white southerners in it. Dripping wet and seething with a feeling I had not known before, I made my way to the bus stop where I would catch a bus to take me back to my part of town.

As I boarded the number 31 cross-town bus, I was steaming and mad as hell. I glared at the bus driver, and after dropping my coins into the fare box, I sat down on the front seat across from the driver as rivulets of water dripped from the hem of my skirt onto the floor and water seeped out from my squishy shoes. The driver, obviously shocked, looked at me and said, “Gal, I don’t want no trouble; you better git on to the back, where you belong.” I responded with a stony silence and a hate-filled gaze. There were no white passengers on the bus, but there were a scattering of black riders seated in the extreme rear, who were quite agitated by my actions. Several of them began hissing at me. They began to gesture in exaggerated movements, urging me to “come on to the back” and “don’t start any trouble.” There was fear for themselves and concern for my safety in their expressions. I looked away from them, unmoved, and stared straight ahead. I had no plan, no rational thoughts. I did not know what I was going to do. All I knew was that I was not going to give up my seat without a struggle. I didn’t know how far I was prepared to go. I thought, I am a human being, not a dog. I am a person just as good as they are. Gone were all the sheltering adults who had done their best to protect me from the bitter realities of being black and female in the Jim Crow South. It was just me and them. For the first time in my life, I was being an “uppity nigger,” and it felt good. Who the hell did white people think they were? I didn’t give a damn what the next moment would bring. All I felt was that I was a “nigger” to be reckoned with!

I was lucky that day. They say that God looks after fools and angels. Clearly I had committed a dangerous act and, fortunately, did not have to pay for it. The driver didn’t call the police or physically throw me off the bus. The few white passengers who boarded the bus didn’t insist on their “skin privilege” that day, but cursed and muttered and stood over me in anger. A few sat down on the opposite side of the bus, glaring menacingly at me all the while. I returned their glares. The black passengers in the back looked on in fear and astonishment and seemed to breathe with a sigh of relief when their stops approached. I reached my destination and got off with tired and heavy steps as the bus sped away.

I stopped trying to find a job in white Memphis after that. A dear neighbor got me a summer job at the Harlem House, a chain of hamburger joints scattered across black Memphis, where I washed dishes until my hands became raw and, when I was lucky, flipped burgers.

I didn’t pull off any other daring acts of courage in Memphis, but I did join the NAACP youth organization and their choir; things were pretty tame in Memphis in the early ’60s, compared to what was going on in other parts of the state and across the South, with the sit-ins and the Freedom Rides. There was no doubt about it: change was in the air. No black person with breath in his or her body was unaware of the rising tide of resistance that was gripping black America.

Spelman College: A Dream Come True

I did get that scholarship to Spelman College. I also received offers from Bennett College (the other black women’s college), Morgan State University, and a small white college in the Midwest that was integrating its campus. I chose Spelman. In my mind it was the most prestigious, and several of my role models—Clara and Alpha Brawner and Mrs. Epps, my pastor’s wife, were alumnae. I graduated third in my high school class of more than two hundred and beamed with pride when my name was called and they read my lists of scholarships and honors. I was really on my way. I had reached for the stars and they were coming closer.

My grandmother was so proud of me. Of course everyone in my family, my school, and my church were, too. But this was so special for Mama, as she had wanted to go off to boarding school when she was a girl so long ago in Arkansas. I was living out her dream of going to college. Mama, my mother, and my stepfather (Rev. Granville Watson) drove me to the campus in Atlanta. I was thrilled as we pulled onto the beautiful tree-lined campus with all of its old, stately buildings. I had to pinch myself to see if I was dreaming. I was assigned to a room in Packard Hall, one of the older buildings on campus. It was like heaven to me and a long, long way from the four-room shotgun house in which I had grown up. Everything was spotless, and the beautiful wooden floors and magnificent wood trim shone like burnished brass. My dream had come true; I was a freshman at Spelman College.

My folks stayed a couple of days for the parents’ orientation. I could see in Mama’s eyes how thrilled she was for me and herself. I promised her that I would do well for her—that I would be good, study hard, and not let anything or anyone come between me and my studies. Her parting words to me were to not get into any trouble with boys or to let anything pull me away from my school work. I promised!

I was so thoroughly caught up in my new life on campus that it was some time before I really noticed that there was a movement going on right outside the tall brick walls that separated Spelman from the housing project. Outside of my Spelman utopia was the same ugly reality I had experienced all my life. In this city with the motto “too busy to hate” was the same Jim Crow. Downtown Atlanta was all white except for the menial laborers. SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) had headquarters in Atlanta and were actively working to destroy legal racism in the city. The Spelman administrators warned us Spelman women to stay clear of any involvement with the Movement. We were there, we were told often, to get an education, not to get involved in demonstrations and protests. They made it clear that any young ladies who got involved would be summarily dismissed, especially those of us who were on scholarships. I heard that! I certainly had no intention of getting involved. I had my priorities straight. This was an opportunity of a lifetime for me; I certainly wasn’t going to blow it.

The Conflict

As fate would have it, I was assigned to an experimental class combining history and American literature. The two faculty members, Dr. Staughton Lynd and Ms. Esta Seaton, were northern white liberals who were well acquainted with the African American struggle for freedom. They set out to awaken us to that incredible history. Throughout my first semester, I became acquainted for the first time with the history and protest writings of my people, and pride in them and their long struggle for justice was awakened. In addition, I met others who fanned the flame of black pride and identity. Vincent and Rosemary Freeny Harding were codirectors of the Mennonite House in Atlanta. Howard Zinn was head of Spelman’s history department. I heard many of his illuminating lectures on the African American contribution to the expansion of democracy in the United States. Another very important factor in my burgeoning transformation was my membership in the West Hunter Street Baptist Church. I joined, following my grandmother’s orders and without knowing of its significance to the Movement: Rev. Ralph Abernathy was its pastor. The church’s first lady, Juanita Abernathy, had a sister who was in my class and invited me to attend church with her. It was somewhat like my own church back in Memphis, the Gospel Temple Baptist Church. Plus it was just a few blocks from the campus. Staying true to my upbringing, I went every Sunday and joined the choir, something that I knew Mama would approve of—and I loved to sing.

While I was totally unaware of it, the stage was being set. What I was learning in my classes, hearing in church about the Movement—mass meetings and even the opportunity to see and hear eloquent sermons from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself in my newfound church—began to erode the defense I had constructed against anything that would come between me and my precious college education. At the same time there were regular visits to the campus by SNCC recruiters, who would alternate between cajoling and lambasting us for not joining demonstrations or sit-ins. They loved to say that we were the next generation of “handkerchief-head-Negroes” who, with all our college degrees, would still be bowing and scraping to “Mr. Charlie,” saying, “yassir boss,” “nawsu boss,” following the white man’s orders ’til the day we died. They would ask, “What is a black man with a PhD?” and answer, “A nigger!” They had some really effective recruiters. One of the best was Willie Ricks, sometimes called “Reverend” Ricks. He’d stand on the campus in his blue-jean overalls (the SNCC uniform) and talk about how the SNCC folks were making history while we studied it.

Many of their barbs hit their target with me. The more I learned about this great “River of Black Protest,” so named and eloquently described by my beloved Vincent Harding in his seminal work, There Is a River, I yearned to become involved.

It wasn’t an overnight change that I went through, however. It was gradual. I began to wear my hair natural. After I appeared on campus with my new Afro, I was called into the dean of students’ office. “What have you done to your hair?” she asked. “I washed it,” I replied. Angrily she responded, “Don’t get smart with me, young lady!” She informed me that I was an embarrassment to the school, as all Spelman women were expected to be well-groomed. But there were no other repercussions and I kept my new hairstyle.

Second, I went against Spelman’s rules and dared to visit SNCC’s headquarters at 8½ Raymond Street. It was within walking distance of the campus, just two blocks from my church home. Not very impressive, rather cluttered and chaotic. But, boy, was the place jumping. There was James “Jim” Forman, SNCC’s executive secretary, whom I later came to idolize. He is truly one of the unsung heroes of the Civil Rights Movement. Always fr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1 Fighting for My Rights: One SNCC Woman’s Experience, 1961–1964

- Part 2 Entering Troubled Waters: Sit-ins, the Founding of SNCC, and the Freedom Rides, 1960–1963

- Part 3 Movement Leaning Posts: The Heart and Soul of the Southwest Georgia Movement, 1961–1963

- Part 4 Standing Tall: The Southwest Georgia Movement, 1962–1963

- Part 5 Get on Board: The Mississippi Movement through the Atlantic City Challenge, 1961–1964

- Part 6 Cambridge, Maryland: The Movement under Attack, 1961–1964

- Part 7 A Sense of Family: The National SNCC Office, 1960–1964

- Part 8 Fighting Another Day: The Mississippi Movement after Atlantic City, 1964–1966

- Part 9 The Constant Struggle: The Alabama Movement, 1963–1966

- Part 10 Black Power: Issues of Continuity, Change, and Personal Identity, 1964–1969

- Postscript: We Who Believe in Freedom

- Index