![]()

1

Chills of Hilarity

“Time and space is everything.”

Randolph County proverb1

“When I moved to Wirt County, I got acquainted with an old man who loved music,” recalled Brooks Hardway, an old-time banjo and guitar player from Braxton County, West Virginia. “He told me one day, he said, ‘I was at a fiddler’s contest one time back in the twenties at Clay Courthouse.’ He said there was six fiddlers in that contest, six of the best. Ed [Edden] Hammons was one of ’em, and he said Ed Hammons was a champion fiddler at that day and time. He said there was some old man in that contest that played left-handed, and he said he took first place over Ed Hammons and the other five a-playin’ a tune called ‘Piney Mountain.’ I said, ‘That’s my Grandpap Santy’s brother.’ That was Frank Santy who winned that contest over Ed Hammons. That’s pretty much something to be proud of, I’ll tell you. Frank Santy could fiddle ‘Piney Mountain’ till it would bring chills of hilarity throughout your body.”2

Hardway’s story hints at some of the concepts that are integral to any discussion of traditional folk music in West Virginia. These concepts include the emotional relevance of the music, legendary musicians and musical lore, origins and influences related to the music, and playing customs. This chapter will explore each of those areas and their intricate interplay.

While some people think old-time fiddle music “all sounds alike” and are not affected by it, others like Brooks Hardway admit the fiddle moves them in significant ways on occasion. I am one of those people. At times I have experienced a strong emotional reaction to the music that is at once euphoric and melancholic. Old-time folk musicians I know relate similar sentiments. Melvin Wine of Braxton County told of being deeply moved as a child by certain tunes his father played. When his father played “Lady’s Waist Ribbon” late at night, Melvin cried in bed.

Something in the music “touched me all over,” Wine recalled. “Dad would play that, and I’d wake up a-cryin’. I just couldn’t stand the sound. I don’t know what about it, but I’d just cry every time he’d play it.”3

For many people, traditional folk music, both tune (instrumental) and song, expresses emotion unequaled in the realms of performance and visual arts. An element of truth in the music touches some essential place deep inside. Traditional folk music involves an ageless musical expression of feeling and emotion over which, at times, the artist seems to have little control. Because of its profound emotional effect and despite a continual barrage for more than a century and a half of popular musical forms, the music of Frank Santy and other traditional folk musicians lives on.

The emotional aspect is much of what attracts people to traditional folk music. Old-time fiddle music isn’t fiction. It represents real emotions long held by the people and culture from which it originated. The tune “Piney Mountain” undoubtedly was not composed to intentionally create an emotionally charged atmosphere that would bring “chills of hilarity” to listeners. Instead it developed through a process whereby human experiences materialize as sound created on musical instruments in many capable hands. The oldest fiddle music in West Virginia and other regions captures a disposition of people, a representation of time, and a portrayal of place.

Folk music is folk art. It is faithful to cultural values and identity. It reflects tradition and expresses emotion found in the folk community from which it comes. Songs, by their nature, express values more overtly than tunes, but even in tunes, certain values can be obvious. Barnyard tunes, such as those that mock chickens, traditionally have been part of the repertoires of rural fiddlers. Since imitation is an ultimate form of flattery, we can deduce that playing tunes that mock barnyard creatures is a way in which rural people express the significance of these animals in their lives. This is also true of fox chase, bear chase, train, highway, and other such tunes that pervade old-time music.

Music that brings “chills of hilarity” goes even further to convey the listener to another mental state, just as folk music in all cultures has done for thousands of years. Folk music from less modernized cultures is almost always associated with dancing (as most traditional fiddle music is) and often has some deeper purpose and meaning.4

Other aspects of old-time music are calming. People identify with nostalgic feelings captured or portrayed in the music. Instead of eliciting feelings of the unknown, as may be suggested by “chills of hilarity,” the music brings about nostalgic feelings of the known, affording comfort and security.

Harking back to another time and place is another effect of traditional folk music that creates positive emotional experiences for many of its listeners. This aspect of traditional folk music can unite people of diverse cultural backgrounds perhaps by transporting them to an earlier time when they were united culturally. After all it is often said that music is the universal language. One does not have to be African American to feel the emotion in blues, or Cajun to feel the undercurrent of emotion in that music. Perhaps fiddle music that helps listeners transcend a state of mind is the result of an unconscious attraction to aspects of the music that in our racial memory5 had deeper meaning and purpose. When Brooks Hardway experiences “chills of hilarity,” is he affected by music in ways that likewise inspired and motivated his ancestors in much the same way that music is used today in some religious settings?6

Furthermore cultural, ethnic, regional, and racial groups continually borrow from one another, causing most musical forms to be related and in constant states of change. Mountain music uses African and European rhythmic, melodic, and vocal traditions, while using melodic forms that display Celtic, Anglo, Germanic, and African emotion and influence. Today meaning and significance in West Virginia folk music is associated more with place and circumstance than with ethnicity.

Expressive music can also be a way of releasing emotions for the musician. Currence Hammonds recalled that his uncle, the famed Edden Hammons (family members spell the surname in different ways), at times became deeply depressed and would go off by himself in the woods, sing or play old lonesome songs, and weep. One such song, “Drowsy Sleepers,” had the refrain, “There’s many a bright and sun-shiny morning/that will turn to a dark and a dreary day.” Edden Hammons was able to express incredible sorrow through his music, which it seems was his way of dealing with his personal depression. Braxton County fiddler Bob Wine used old-time music for similar purposes.7

Louis Watson Chappell was an English professor at West Virginia University and a pioneer of field recording in the state who recorded numerous West Virginia fiddlers and singers between 1937 and 1947. Chappell noted that during one recording session Edden Hammons played an old piece and started to tell about an uncle who had played the tune. As Hammons thought about the association of his uncle and the tune, his emotions overcame him and he could not continue to play. Fiddlers often have sentimental or nostalgic connections to the people from whom they have learned in addition to emotional reactions to the music itself.

When coupled with intricately bowed rhythms and engaging melody lines, traditional Appalachian fiddle tunes can create compelling, sometimes even eerie or spooky music. A debate has gone on for years as to whether the emotions elicited by old-time, traditional music are positive and virtuous or negative and evil.

“Here a feeling for the supernatural sets in,” wrote Emma Bell Miles in a 1905 description of Appalachian vocal music. “The oddly changing keys, the endings that leave the ear in expectation of something to follow, the quavers and falsettos, become in recurrence a haunting hint of the spirit world—neither beneficent nor maleficent, neither devil or angel, but something—something not to be understood, yet to be certainly apprehended.”8

As Miles indicated, something unexplainable about the music associates it with the “spirit world,” a world of the unknown when found in a secular setting. The association of fiddle music with forces of evil is widespread and has old-world precedence.9

Clyde Case of Braxton County acknowledged the eerie quality of some old-time fiddle music and told of a neighbor who played peculiar music. “French Ballangee up here, he had a key he played in, he called it the discord key,” Case said. “He wouldn’t hardly ever tune up in that, just once in a while, he’d tune up and play a few.”10

The “discord key” was probably what central West Virginia fiddlers call “Old Sledge tuning.” The DAEA fiddle tuning (high to low) allows for a droning first string accompanied by a melody on the second and resonant bass strings. This and other scordatura (unusual or “open” tunings used to create special effects) were popular in early sixteenth- and seventeenth-century lute music and seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European violin music. Forgotten among most classical musicians today, these tunings have been preserved in folk tradition in West Virginia.11

Mythical motifs are suggested in folk tunes through both the sound and mood brought about by the modes in which they are played. Tunes attain further mythical status through accompanying narrative and lore. The supernatural elements of West Virginia folk music are even clearer in the verses of songs.

Phyllis Marks of Gilmer County sings at least four songs with overt supernatural elements. “The Cherry Tree Carol” and “The Friendly Beasts” have a Christian context, with the supernatural element attributed to the power of God. In “Bow and Balance to Me” (Marks’s version of the old Child ballad #10 “The Twa Sisters”), a fiddle made from body parts of a drowned girl supernaturally plays “by my sister I was drowned” when “on the fiddle the bow did sound.” Marks’s “Molly Bender” ends with the ghost of a slain woman appearing at her intended’s trial.12 A similar motif is documented in West Virginia law. The ghost of a deceased girl appeared to her mother and revealed the murder of the girl. After the body was exhumed on this evidence, an autopsy proved the ghost to be correct. A suspect’s conviction in 1897 based on this evidence is a rare case in which a supernatural event convicted a murderer.13

Certain instruments also were identified as supposedly having supernatural powers and satanic affiliations. Stories about fiddles with mythical properties are widely known.14 A Hammons family tale centers around a fiddle that played itself after “Old Pete” Hammons had played it later than midnight at a Saturday night dance. When Pete returned home from the dance after breaking the Sabbath, he hung the fiddle on a peg and went to bed. By itself the fiddle started playing “The Devil in the Woodpile.” Pete had to burn the fiddle in the fireplace to get the music to stop. According to Currence Hammonds, Pete never played the fiddle again.15 In a Barbour County tale an unwanted visitor was rebuked by an “evil” fiddle. Just before admitting a visitor, a fiddler placed his fiddle-playing wife behind a thin board wall upon which a violin hung. He told the visitor he could make the fiddle play itself and, on giving the proper cues to his unseen wife, spooked the fellow into never coming back.16

Some organized religions have recognized the powerful emotions evoked by secular folk music and use this to advantage. Others do not, but people will continue to feel these emotions. Ancient music may affect people in ways that are joyful, mournful, seductive, chilling, or mysterious, but it also may be inspirational in a positive religious sense. It remains for the listener’s judgment as to whether it is a heavenly blessing or sin’s enticement, whether it is a positive celebration of life or a negative reflection of evil. These dilemmas have plagued zealous Christians for centuries.17

Of course the emotional aspect rendered by any music depends on the forte of the musician. Certain fiddlers were expert at evoking “chills of hilarity” and other strong emotions. Jack McElwain and Edden Hammons were top fiddlers in the region, with McElwain usually receiving the nod as the best there was. Ernie Carpenter, who remembered beating Hammons in a contest one time, said no one ever doubted that McElwain would win any contest in which he played.18 “Blind Ed” Haley, from Logan County, another old-time fiddler who gained much admiration in West Virginia, traveled around the southern half of the state playing requests for handouts and tips. Brooks Hardway remembers Haley’s visits to the area:

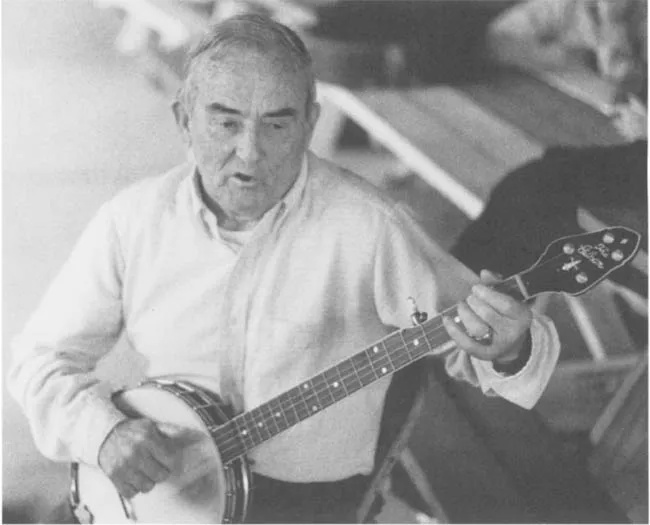

Brooks Hardway, 1988. (Photograph by the author.)

I’m a pretty good judge of what good fiddlin’ is, and Ed Haley was the slickest, hottest—he’s another fellow that was fifty years ahead of his time. Ed Haley could lay the leather on that fiddle bow. And so smooth—it was out of this world.

I walked up in the courthouse at Spencer one time, that was in the twenties—there was a crowd in the courthouse yard—and I walked in and there set Ed Haley, a-fiddlin’. He had a tin cup settin’ there on a little stand, and Ed Haley wouldn’t play unless that tin cup kept rattlin’ with nickles and dimes. . . .

Laurie [Lawrence] Hicks—was rough as a cob, but, my my, he could put stuff on a fiddle that was out of this world. He would go down to Charleston and bring Ed Haley up and keep him a week, maybe two. . . . Laurie picked up a lot of his stuff too. Ed enjoyed that. That’s free board for Ed, you see, and at that day and time it was nippety-tuck to make a livin’ if a man didn’t live on a patch of land somewhere. . . . When Laurie Hicks was on his dyin’ bed, he requested, he said, “I would like to have Ed Haley to play a few tunes over my grave, when I’m dead and gone.” And Ed Haley made a special trip up to Stinson and fiddled over Laurie Hick’s grave. They said he played some of the sweetest tunes you ever listened to. He took a little group with him, and he played the fiddle over Laurie Hick’s grave. Th...