![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Experiencing the Landscape

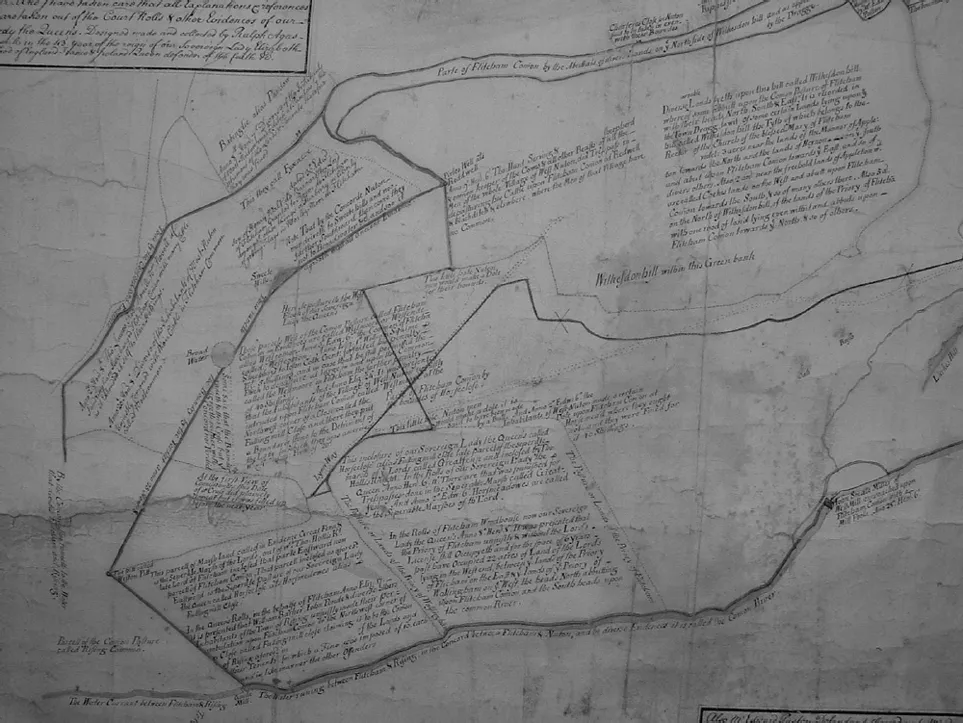

In the closing decades of the sixteenth century the lords, tenants and inhabitants of a group of neighbouring villages around Flitcham, in west Norfolk, set about the difficult and controversial task of defining their boundaries across the open commons and heaths. Unable to reach agreement the matter was presented before the central equity courts in 1592 and again in 1602 (TNA: PRO, E178/1587). During litigation proceedings a number of oral testimonies were gathered from the elderly inhabitants of the area and a survey was made of the grounds in question (Figure 1). Seventy-year-old John Creede the elder, a husbandman, spoke about the landscape he had known since he was aged fourteen. From memory he presented a detailed account of the boundary encompassing Flitcham and Appleton common. Beginning at the ‘clay pits’ he described the course of the bounds extending north to a place called ‘Purrells gate’ near to ‘Purrell stone’, then to ‘Sandgate’ and to ‘Kippestowe’ before turning westwards to the north side of ‘Willesdon Hill’ from there to ‘Purrell Well’ also known as ‘Redwell’ and to ‘Sweete Hill’ then to ‘Broadwater’, ‘Whetstone Pit’ and to the mill on the river. Creede was mindful to corroborate his personal recollection of the bounds by presenting his knowledge as part of the collective memory of the village. He went on to confirm that this was the route taken during Rogation week when the parishioners perambulated their bounds, which he could remember taking place many times since the reign of Henry VIII. Creede drew attention to the significance of two boundary features in particular, noting how the ‘townes of Flitcham and Babinglie did meete togither at Whetston pitt’ and ‘the men of Flitcham and Newton did meete at Purrell Stone’.

Creede went on to elaborate on the meaning and value of these various landmark features in relation to the complex arrangement of local farming practices, customs and land use rights. While confirming the tenants of the three lordships of Flitcham held common rights to pasture their cattle on the heath throughout the year, he also highlighted a number of internal divisions. The tenants, for example, were only permitted to common on ‘Willesdon Hill’ when it lay unenclosed and unsown and were allowed to take whines and furze for their fuel except from ‘Willesdon Hill’ and a place called ‘Porters Whines’. In addition, the tenants of Flitcham had no right to pasture their animals to the north of a ‘faire mencon of a broade oulde ditche’ which led from the great stone known as ‘Purrell Stone’, in a south or south westerly direction, to ‘Sandgate’. ‘Willesdon Hill’ was also employed to delimit manorial grazing rights. According to Creede the flock of sheep belonging to the lordship of Appleton were not permitted to graze any further than the south side of the hill, for that was the territory of the Flitcham flock.

FIGURE 1. Detail of a map of Flitcham drawn up in 1601 in connection with a long running dispute concerning the course of boundaries across the open heaths shared by the lords, tenants and inhabitants of Flitcham and neighbouring townships of Appleton, West Newton and Babingley (NRO, Flitcham, 407).

John Creede’s description of his local landscape illustrates well the central themes of this book. He conveys a powerful sense of the indivisibility of the physical experience of landscape and demarcation of local social and economic relations. Mapped out on the ground the intricate web of village, and intravillage jurisdictions, provided a tangible and visible medium through which Creede articulated his memories and strong attachment to the place he had known since he was a child. Creede’s knowledge was deeply rooted in his conception of the past, based on his everyday experiences of working the land, his participation in public events and rituals, and also his comprehension of material antiquity in the landscape. Creede integrated a network of natural and archaeological features, surviving from various pasts, within a material language of jurisdiction and right.

Until relatively recently the focus of landscape archaeology has been predominately concerned with investigating past land use and how local environments – soils, topography, climate, availability of natural resources – shaped patterns of demography, agriculture and settlement. In order to understand the evolution of the modern landscape, research has been necessarily preoccupied with producing typologies of material artefacts and landscapes, each relating to different segments of time. Over the last two decades the emphasis has shifted, with many writers calling for greater consideration of how people living in the past experienced and perceived their physical surroundings. This move away from focusing on environment and economies towards an understanding of the landscape as a social construct, has led to innovative and exciting research much of which, as will hopefully become apparent in these pages, is enormously inspiring. Through a detailed examination of contemporary maps and court deposition evidence an important contribution can be made to our understanding of the social, cultural and economic contexts of post-medieval landscape history.

One of the principal aims of this book is to develop an interdisciplinary approach by bringing landscape history and social history closer together. Early modern social historians have spent little time thinking about the significant role the landscape played in the mediation of day-to-day social relationships. In the majority of writing dealing with this period, the landscape features only as a backdrop to social and economic relationships and construction of individual and collective identities. Yet the landscape was used as a signifying system, elements of the past were appropriated and new features were made, in order to express individual and collective beliefs and convictions regarding matters such as land use rights, local customs and traditions. As this book hopes to demonstrate, by examining a wide range of sources, many of which have not been used in any systematic way by landscape historians, an important contribution can be made to our understanding of the social context of post-medieval landscape history. This study seeks to recapture something of the ways people living in the post-medieval period valued and gave meaning to the landscape for a range of reasons other than just regarding the economic potential of the land. Of central concern is an understanding of the landscape as a lived environment imbued with multiple and diverse meanings and associations particular to the time and place.

Debating the Post-Medieval Landscape

Research on the transformation of England’s rural landscape since the sixteenth century, has been mainly concerned with the development of capitalist systems of production and the ‘commodification’ of the landscape (Johnson 1996). Drawing on anthropological research Christopher Tilley has posited a firm distinction between the experience of landscape in pre-capitalist/nonwestern societies and capitalist/western societies (Tilley 1994, 20). He employs a number of binary relationships to outline the underlying characteristics of each. ‘Pre-capitalist spaces’ are ‘ritualised’ and ‘sanctified’, imbued with ‘myth and cosmology’, and ‘ritual knowledge’. ‘Capitalist spaces’, in contrast, are ‘desanctified’ backdrops to rational, economic action, they are devoid of meaningful depth and ‘set apart from people, myth and history, something to be controlled and used’ (Tilley 1994, 21). Until recently, most post-medieval landscape studies have, to varying extents, reinforced this distinction. The subject of agrarian improvement for instance, has led many to focus on economic determinants shrouding the debate in statistical analysis concerning measurements of land productivity and crop yields (Overton 1996; Campbell and Overton 1991; Glennie 1988). In these studies the achievements of ‘rational’ capitalist farmers in combating the limitations imposed by nature are placed at the forefront of debate (Williamson 2002).

A pre-capitalist/capitalist dichotomy, however, underestimates the diverse understandings of place and landscape in capitalist societies (Cosgrove and Daniels 1988; Kealhofer 1999). As Kealhofer (1999, 62) points out individuals in modern capitalist societies do create ‘backdrops’ but ‘these are evocative and symbolic, not two-dimensional and meaningless’. Research into the enclosure and re-structuring of elite landscapes clearly illustrates the symbolic and ideological meanings embodied in the physical environment in the eighteenth-century (Williamson 1995; 1998; Gregory 2005). Among the most influential writers, Denis Cosgrove has defined the landscape as ‘a cultural image, a pictorial way of representing, structuring or symbolizing surroundings’: a response associated with seventeenth-century landscape painting, and with the idea that the viewer is situated outside the landscape (Cosgrove 1988). The landscape therefore is not merely a physical entity, a collection of objects and structures arranged in a particular way, but also a way of seeing, which can be used to project political, social and ideological perspectives. Meaning is conveyed through a symbolic language – referred to by Cosgrove and Daniels as ‘an iconography of landscape’ – in which the landscape, like a painting, is analogous to a text, something to be decoded and interpreted (Cosgrove and Daniels 1988, 1). Cosgrove is concerned with the origins of the modern idea of landscape and a particular way of seeing among the wealthy elite. His approach is, however, a useful one for understanding the ways other social groups, in other contexts, may have conveyed meaning through their (sub)conscious manipulations of the physical environment (Johnson 1996).

In recent years these kinds of approach have also found favour among anthropologists and archaeologists, especially those concerned with the prehistoric past. Edited volumes by Ashmore and Knapp (1999), Ucko and Layton (1999) and Bender (1993) have, for example, emphasised the interpretation of archaeological sequences in terms of cognitive patterns, rather than simply as a consequence of mundane aspects of daily subsistence. Broadly speaking, many of these scholars would take issue with Cosgrove’s premise that the ‘viewer’ can detach her/himself from the landscape as a subjective interpreter: in Gabriel Cooney’s words, ‘a person’s perception or mental map of a place is what underpins his/her actions rather than the objective reality of that place’ (Cooney 1994, 32). Building on these conceptual ideas the archaeologist John Barrett has proposed a theory of ‘inhabitation’. He cautions against taking the meanings given to material artefacts or places as self-evident and stresses the importance of understanding the particular social and cultural contexts from which meanings were derived: ‘meaning is something recognised by an observer, it is not some quality inherent to the place or the monument’ (Barrett 1999, 27). Even at the time of their original conception the intended meanings attached to places, or indeed entire landscapes, could be subject to a range of interpretations and, obviously over time, the scope for re-interpretation and re-invention widens (Bender 1993).

The shift away from attempting to elucidate the origins of monuments and landscapes, to think instead about how such features were interpreted by subsequent societies, is among the most significant theoretical and methodological developments in recent years. Scholars interested in the contextual meanings of commemorative monuments have been forthcoming in adopting such approaches (Finch 2003; Tarlow 1999) but as yet post-medieval landscape archaeologists and historians have been generally slow to engage with theoretical debates taking place within the wider discipline. In the majority of work on this period, there has been a tendency to construct a linear narrative of change focused on enclosure and agrarian improvement. Understanding the landscape, as it was ‘inhabited’, should not be confined to prehistory; it is an effective approach for the post-medieval period.

Enclosure

Enclosure has long been a major area of enquiry and debate among scholars interested in the formation of the modern rural landscape. On this subject, Matthew Johnson’s An Archaeology of Capitalism (1996) is among the most innovative and thought-provoking studies to date. From an archaeological perspective Johnson interprets the major structural changes implemented by enclosure as the physical expression of a deep-rooted subconscious shift driving the forces of capitalism. Johnson’s objective, to look beyond economic explanations that have dominated our understandings of enclosure, is a salient reminder that for early modern societies matters of everyday life were not neatly compartmentalised. His argument, however, has been criticised on a number of grounds. Tom Williamson has discussed some of the pitfalls in adopting such a unifying approach. In particular he highlights the importance of regional variation regarding both the chronology and character of enclosure (Williamson 2000a). During the early modern period farmers enclosed and converted their arable lands to pasture in order to specialise in livestock husbandry. Outside the Midland core where large landowners undertook wholesale enclosure schemes across extensive areas, enclosure before the eighteenth century was mainly of a gradual piecemeal nature. Moreover, in prioritising enclosure as the dominant structuring force of nascent capitalism, Johnson implies that enclosed land provided the best environment for commercial farming which, as others have pointed out, was not always the case (Havinden 1961; Williamson 2000a). Within the main arable-producing regions – the wolds, downs and heaths – open field systems continued to operate within ostensibly capitalist landscapes. But both sides of the argument assume that farmers shared a common objective regarding the most profitable way to exploit the land.

Johnson’s cultural model of enclosure, and the more general concern to map regional patterns of change, have both tended to underplay the confused reality of enclosure and above all its antagonistic ramifications at a local level. Investigations into the local implementation of enclosure provide a rather different story – one of conflict and dispute over the best and most profitable way to use the land. Considerable research has been carried out on the social consequences of enclosure, especially in areas, in the Fens and pastoral-industrial regions for example, where the enclosure of common land was met with strong and sustained resistance (Lindley 1982; Manning 1988, see also Edwards 2004; Falvey 2001; Hipkin 2000). Though not always culminating in the levels of riot and insurrection associated with these areas, enclosure was nevertheless an emotive and divisive issue for the inhabitants of villages located within both arable and pasture farming districts in Norfolk. This was as much the case in districts defined by piecemeal enclosure, often described by landscape historians as a consensual and straightforward agreement between neighbouring farmers, as it was in areas dominated by open field systems. As we shall see within many Norfolk villages the creation of enclosed, private landscapes was an uneven and, for a time at least, an uncertain development. In many places, until the late eighteenth century, multiple use rights and customs defined the landscape. Tensions existed between the aspirations of the individual and the moral boundaries of obligation and right set by the ‘community’. Before enclosure and privatisation could be achieved this intricate web of communal rights had to be dissolved, a process of deep social and economic controversy in many villages.

Landscape and Social History

Early modern social historians have demonstrated the importance of custom as quite literally a field of conflict in the everyday life and politics of local societies (Wood 1999; Wrightson 1996, 22–25). Local customs gave authority to the claims of the inhabitants of a particular place to utilise the landscape in a number of ways: to graze their livestock on the commons and fallow open fields; to glean for ears of corn after harvest; to gather fuel and wood, and to dig for clay on the commons, for example. The authority of custom was based on continuous usage and knowledge of the past (Thompson 1991; Wood 1997; 1999). Handed down from generation to generation, local knowledge of land use rights was presented as having existed since ‘time out of mind’. In the attempt to legitimate their claims of antiquity plebeians deliberately asserted that their customs were static; that they were fixed in time and space (Wood 1997). By proving that a custom was in continuous usage, since before anyone could remember, and providing no written records were recovered to the contrary, was confirmation enough of its authority before a court of law (Wood 1997). For all that precedence was given to proving antiquity, custom was nevertheless flexible – scrutinised, manipulated and tailored to suit the needs of the present. Its adaptability was part of its enduring strength as people of all social rank endeavoured to take full advantage of their situation (Thompson 1991, 102; Wood 1997; 1999). Landowners, tenants and commoners each played an active role in transforming their lived environment through the negotiation of custom and right.

Andy Wood’s study of the Peak Country offers a compelling insight into the powerful concept of custom among the free-miners of the region. He shows how custom shaped everyday social relations and, especially during periods of dispute, reinforced a common sense of purpose and identity within the free-mining community (Wood 1999). However, more attention needs to be paid to assessing the material and spatial contexts of these social interactions and developments. Local customs and land use rights were attached to the land and it is this materiality that is of great importance for our understanding of the landscape history of the early modern period. Physical space was defined by multiple layers of access rights and customs often attached to different jurisdictions – the manor, parish and township – which interlocked in various and complex ways. As John Creede’s account indicates, the identification of various landmarks became intrinsic to the definition of custom and right. It was through the practical knowledge of the landscape, through the memory of the past and the ongoing physical experience of living and working in a particular place, that people defined their social and economic identities.

A stronger alliance between social history and landscape history can offer new insights on other themes and processes of the period. In an influential article written over a decade ago, Keith Wrightson examined the politics of the parish in early modern England (Wrightson 1996). Interweaving the major themes of early modern history – politics, religion, governance, and economic and cultural developments – he explored the complexities of change at a micro-level. In a number of important ways the issues outlined by Wrightson, and other historians since, are useful for our understanding of the inhabited landscape. The rural landscape was not simply an economic resource, nor was it merely a backdrop to social action; rather the landscape provided the medium through which social, political, religious and economic relations were mediated.

The Dissolution, end of pilgrimage and attack on purgatory, shaped the development of the landscape and spatial context of peoples’ lives in a number of important ways, which have yet to be fully explored by landscape historians. As we shall see the Reformation had a profound impact not only on local social relations but also on the spatial configurations of religious beliefs and practices outside the parish church. In Norfolk, the closure of monastic houses, and mutilation of material artefacts, sculptures and paintings was accompanied by the closure and ruination of unprecedented numbers of religious buildings and structures: a process that fundamentally altered the spatial framework of sixteenth-century religious topographies. The material changes brought about by government legislation had further repercussions for the organisation of local administrative structures.

Religious reform was intertwined with the growing power of the Tudor State, which had important implications for local social and political relations, and also for the physicality, and meaning of place and belonging (Hindle 2000; Wrightson 1996). In the sixteenth century, renewed population growth and concomitant rise in the demand for food and high grain prices was offset by periods of economic dearth and depression. The 1590s stands out as a particularly harsh decade; badly affected by sporadic periods of harvest failures and disease, which brought distress and impoverishment to many small farmers and cottagers. The dispossessed migrated in search of work to urban centres or, as in other parts of the country, they travelled to wood-pasture and forest areas attracted by their extensive commons, which offered to them a means of subsistence. This gave rise to tensions as settled inhabitants and commoners sought to guard their rights to common resources and who frequently turned to the law courts for arbitration (Hindle 1998; 2002, 158–160). The institutionalisation of the Poor Laws at the end of the sixteenth century consolidate...