![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Chatsworth in Context

Setting the scene: Chatsworth’s place in the world

For those not intimately familiar with upland landscapes such as that around Chatsworth, and those in the Peak District more generally, it may come as a great surprise that the historic landscapes here are as rich as they are. Commonly, upstanding features such as a 4000 year old ritual monument can sit alongside a medieval earthwork of 1200 AD or a lead mine worked 300 years ago. The archaeological legacy is far more than a few scattered sites, the whole landscape has great time depth. Everywhere you look has a rich palimpsest of features creating a land imbued with the past and strongly evoking the many generations of people who have inhabited this place and helped shape what we see today.

At Chatsworth we see the Peak in microcosm. However, at this one special place, not only is survival of evidence particularly good, but the landscapes around the Estate are diverse and tell contrasting stories. Chatsworth House and its gardens, with the grand landscape park beyond, are the icing on the cake as they create an exceptional centrepiece. To pick out some highlights, in the park started in 1758–59 are some of the best archaeological earthworks of medieval open fields and later enclosure in Britain. On the Estate moorlands there are exceptional survivals of prehistoric stone circles, barrows, fields and settlements. In contrast, the Estate’s enclosed farmland tells of continuous occupation and gradual changes made over the last thousand years.

While this book concentrates on the archaeology of this ‘Great Estate’, it also tells a broader story throughout, drawing on the links between Chatsworth-owned land and the wider landscape.

Chatsworth and the surrounding Estate villages and farms are different things to different people. For a few, their home and place of work is here. For many, Chatsworth is a place to visit, to wonder at the splendours of the House and gardens with their spectacular parkland backdrop. Most visitors appreciate the impressive classical architecture, and the antiques and paintings therein. The gardens, with their trees, plants, fountains, cascade and grottos are equally fascinating. The long history of the Cavendish family, here since 1549 and bearing the Duke of Devonshire title since 1694, draws people here. Some wander into the park to take the air and enjoy the views and the ancient oaks, or visit the model village of Edensor. Others are on missions to the garden centre or the farm shop. Some visit the surrounding somewhat quaint Estate villages and follow footpaths through the farmland, woods and moorland to enjoy the wider countryside and its plants and animals.

FIGURE 1. Chatsworth House from the park, with Stand Wood behind.

However, there is a complementary side to Chatsworth Estate which is equally fascinating, and one that not many people have previously had access to detailed information about, namely the historic landscape and its archaeology. This book seeks to redress the balance.

Recently another book on Chatsworth’s park and gardens has given an in-depth picture of their history and what went before.1 The current offering is very different in scope and emphasis. Here the whole of the Estate landscape, including the extensive farmland and moorlands beyond the park, are included, and the book concentrates on the visible archaeology and what this can tell us about the past. Other books on Peak District archaeology are available, such as ‘The Peak District: Landscapes Through Time’, which gives an overview of the archaeology of the region.2 The current Chatsworth book complements this overview, covering the same themes but looking at one place in more detail.

Beyond the House, gardens and landscape park at its heart, the Chatsworth Estate spreads over many acres of enclosed farmland in the valley of the River Derwent, around Edensor, Calton, Beeley, Baslow and Bubnell. To the east there are extensive bleak moorlands and scattered farmsteads. All these areas have rich and diverse stories to be told, derived from the many archaeological vestiges that remain.

Archaeology is about how people have lived and how they have affected the land in the past. It studies what they have left behind. This is not restricted to obvious archaeological monuments such as prehistoric barrows, ancient hillforts, churches and castles. It includes all the remains of human activity through time that have survived above or below ground to the present day, whether 5,000 or 50 years old. At Chatsworth, this includes the relics left by farmers, smallholders, labourers, millstone makers, quarrymen, and miners of coal and lead, as well as members of the landed aristocracy. Equally important is evidence for people crossing the land to and from the Derwent Valley around Chatsworth. They came and went from markets, workshops and factories, as well as farms, villages and towns. Meat, milk and cheese from local farms were sold in nearby towns and cities. Beyond the Peak there were important industrial and manufacturing areas to the east around Chesterfield and Sheffield. Similarly, there was trade with the salt-producing areas of the Cheshire Plain and potteries in Staffordshire and to the east of the Pennines. Millstones and lead from the Peak went to Hull, from where they were shipped to other parts of Britain and in the case of lead, to the rest of the world.

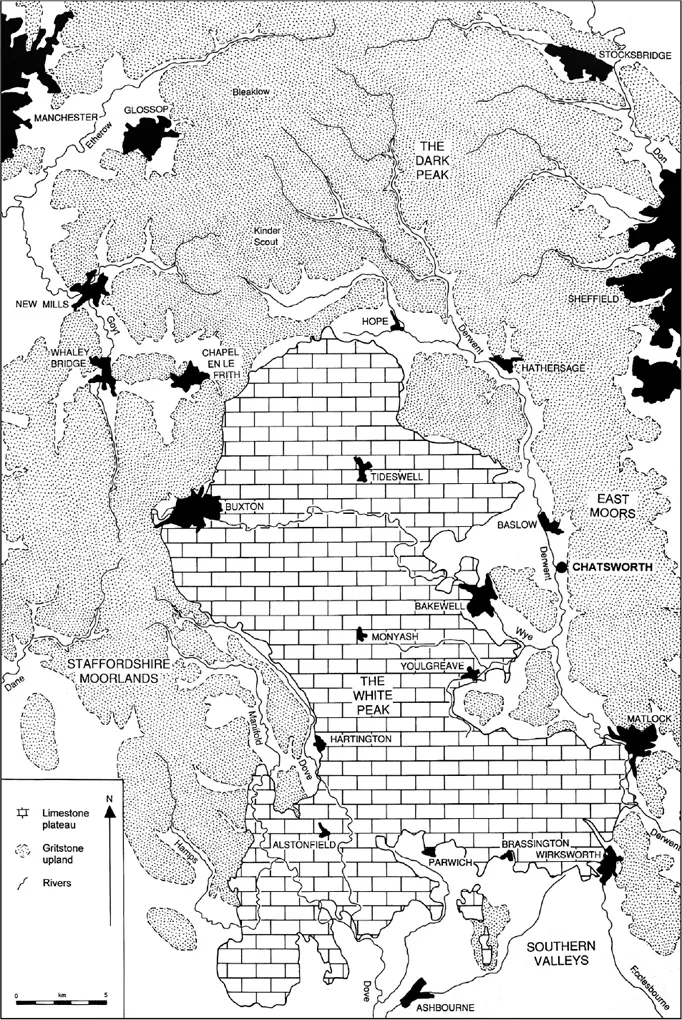

FIGURE 2. The Peak District and the location of Chatsworth in relation to surrounding cities, towns and larger villages.

The Cavendish Family at Chatsworth

The Cavendish family first became involved in Chatsworth in 1549, when William Cavendish and his wife Elizabeth (‘Bess’) of Hardwick purchased the old hall here, together with its deer park on the slopes above and farmland on both sides of the river. Over the generations, their descendants, soon Earls of Devonshire and later Dukes, have periodically rebuilt, enlarged and modified the House and its gardens, adding to their splendours according to the fashionable tastes of different generations.3 The present landscape park to the north, south and west of the House was started in 1758–59 under the direction of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and finished several years later. The medieval deer park, sited on the land running high above the House to the east, became redundant and later in the 19th century was largely subdivided into fields and plantations out of view from the House. Over the generations the Estate holdings were also gradually extended to their present bounds. This included an acquisition in the early 19th century, when large tracts of land were exchanged with the Duke of Rutland, which allowed the 6th Duke of Devonshire to extend the park a significant distance northwards.

Much of the designed landscape of the park we see today was created in the 18th century and modified in the 19th. The present gardens owe much to the work of Joseph Paxton and the 6th Duke in the 1820s–50s. The extensive farmland has had the Estate’s stamp applied in more subtle ways. Some parts have developed in organic fashion over many generations. However, other areas of fields are pieces of ambitious planning, with what was there before swept away and replaced with the then current ‘state of the art’ field layouts and farm buildings. Other places were taken out of agricultural production at the ‘home farm’ or tenanted holdings and planted with trees as both long-term cash crops and decorative landscape features. These types of change are one of the characteristics of great estates; they could afford to make rapid radical alterations and improvements, whereas at the other end of the spectrum the typical hill farmer could not. The Chatsworth moorlands owe their survival not so much to their altitude and poor soils, but more critically to the family’s interest in grouse shooting in the 19th century; elsewhere in the Peak similar land away from the estates of the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland was often enclosed and improved.

In the first half of the 20th century, Chatsworth, like many great estates, fell upon relatively hard times and no radical changes to the landscape were made. However in 1950, when the late 11th Duke inherited, a reverse in its fortunes was instigated. He, and the now Dowager Duchess, spent decades building Chatsworth into one of the most attractive and successful of Country Estate tourist businesses. It is now visited by many thousands per year, who come to spend time at this most tastefully presented of ‘great houses’. The 12th Duke and Duchess have now taken up the reins.

The Cavendish family also once owned much land elsewhere in the Peak District and North-East Derbyshire, as well as in other parts of England and Ireland; while some is still in their possession, a number of their estates were sold in the 20th century. These lands are all beyond the scope of this book, which exclusively describes the extensive current holdings in the vicinity of Chatsworth. To draw this distinction, the areas described are referred to throughout as the ‘Core Estate’.

The Chatsworth landscape

This landscape of great scenic beauty lies in the heart of the Peak District. The House and park are in the Derwent Valley, with high wooded scarps to the east and desolate moors beyond, each with distinctive but very different types of appeal. Elsewhere in the valley there are extensive areas divided into fields, with villages, hamlets and farmsteads. These again have their own charm, with vernacular stone buildings, grassy fields, hedgerows, field walls, and woodlands.

No part of the Estate, or for that matter the Peak District has been left untouched by people over the last 10,000 years. While the geology of the area has determined the landforms and to an extent governs what grows here, it is people who have shaped everything that we see today from the soil upwards. Even the mix of plants and animals is determined by how we have managed and continue to manage the land. At a landscape scale nothing is how nature would have intended if left to its own devices. After the last Ice Age trees spread and carpeted much of the local landscape. They would still be here if it was not for people; many of the fine landscape vistas for which the Peak District is famous would not be visible. Even Chatsworth’s heather moorlands are not ‘natural’ in the sense that these are entirely the product of people removing trees in prehistory and maintaining upland grazing here ever since.

The historic landscape in the Chatsworth Core Estate is not one integrated whole but has three distinct parts which will be frequently separated throughout the book, each with strongly contrasting geology, topography, history and surviving archaeology. The parkland with the House and gardens is at the heart – the enclosed farmland surrounding this, which is also focussed on the Derwent Valley but includes shelf-lands to the west – and the high moorlands lie to the east. Each has great time depth with a wide range of archaeological features, but before we come to these we need to understand something of the underlying geological backbone.

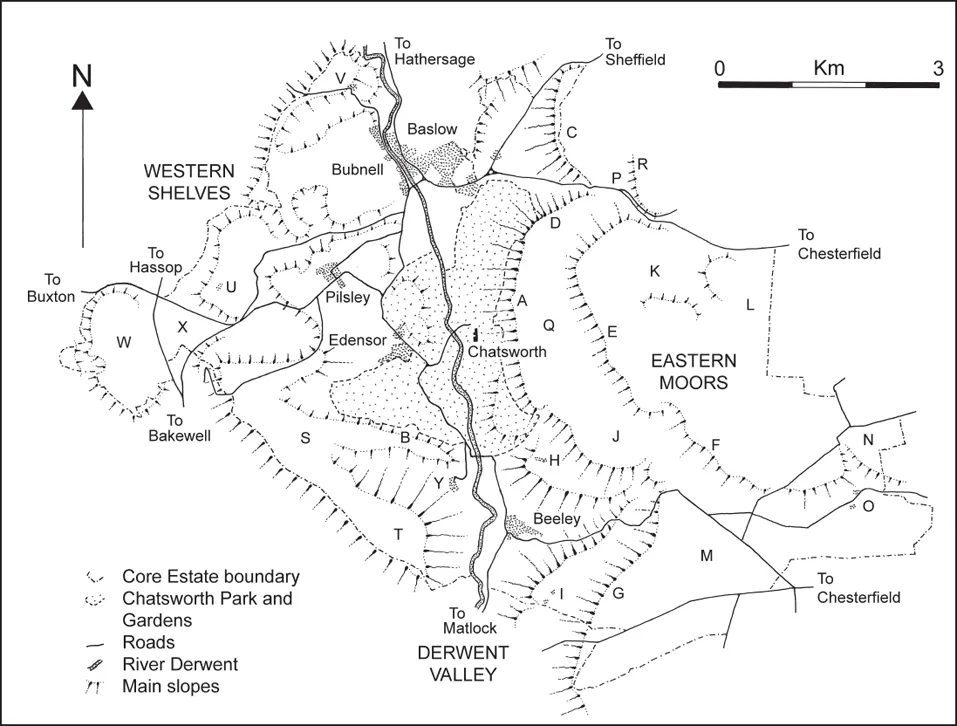

FIGURE 3. The Chatsworth Core Estate, showing topography, places and roads (Places mentioned in Chapter 1 – A: Stand Wood, B: New Piece Plantation, C: Gardom’s Edge, D: Dobb Edge, E: Bunkers Hill, F: Harland Edge, G: Fallinge Edge, H: Beeley Hilltop, I: Fallinge, J: Beeley Warren, K: Gibbet Moor, L: Brampton East Moor, M: Beeley Moor, N: Longside Moor, O: Harewood Moor, P: Robin Hood, Q: The Old Park, R: Birchen Edge, S: Calton Pasture, T: Lees Moor, U: Birchill, V: Bramley, W: Cracknowl Pasture, X: Birchill Flatt, Y: Calton Lees).

The natural background; constraints and resources

The River Derwent, which Chatsworth House overlooks, is one of the key features of the Peak District, providing a topographical ‘artery’ running north/south between higher ground to east and west. The main scarp of the gritstone uplands to the east dominates the scene. The land beyond is high and the peaty soils have inhibited settlement for the last two millennia except for an occasional farmstead. In prehistory this land was inhabited more widely, at a time after the natural forest was first cleared, when soils were more fertile than they are today. These eastern moors flank the Derwent for much of its upper course. They run from above where its headwaters enter the broader Hope Valley at Bamford some 10 miles north of Chatsworth, to where the river starts to run out of the upland beyond Cromford a further 10 miles to the south. The start of the central limestone plateau of the Peak District, historically an important area for settlement, agriculture and lead mining, lies only about 3 miles west of Chatsworth. However, there is very little limestone country within the Core Estate, the exception being at Cracknowl Pasture. Between the Derwent and the plateau, there is a local dissected area of further shelves, higher ridges and steep scarps, where the rocks comprise beds of sandstone and shale.

The Derwent Valley

The River Derwent follows a deeply incised valley past Chatsworth at a little over 100m above sea level, with the land a short distance away to the east often rising steeply. Only at Baslow and Beeley are the valley-bottom lands wider due to brooks entering from the east. To the west, in places the valley side rises only gradually to low shelves, as around Bubnell, Pilsley and Edensor. These topographic considerations have had a strong influence on where the main villages are located, sited at places where good low-lying agricultural land is maximised. Parts of the flat valley-bottom land would have been liable to flooding, particularly prior to canalisation of the river by the Estate and before the building of reservoirs in the Upper Derwent Valley just after the turn of the 20th century.

The main rock type in the valley is easily eroded shale of the Middle Carboniferous era. Higher in the geological sequence, there are also interleaved thin beds of sandstone and siltstone, together with much thicker beds of coarse sandstone known as millstone grit. These erosion-resistant beds form the tops of the valley-side scarps.

Shale-based soils in the valley, derived from decomposition of this parent rock, are heavy and poorly drained clays. However, the bottom lands often have alluvium deposits containing many sandstone cobbles which are relatively infertile compared with those in the lowl...