- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

From Traditional Fault Tolerance to Blockchain

About this book

This book covers the most essential techniques for designing and building dependable distributed systems, from traditional fault tolerance to the blockchain technology. Topics include checkpointing and logging, recovery-orientated computing, replication, distributed consensus, Byzantine fault tolerance, as well as blockchain.

This book intentionally includes traditional fault tolerance techniques so that readers can appreciate better the huge benefits brought by the blockchain technology and why it has been touted as a disruptive technology, some even regard it at the same level of the Internet. This book also expresses a grave concern on using traditional consensus algorithms in blockchain because with the limited scalability of such algorithms, the primary benefits of using blockchain in the first place, such as decentralization and immutability, could be easily lost under cyberattacks.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 Basic Concepts and Terminologies for Dependable Computing

1.1.1 System Models

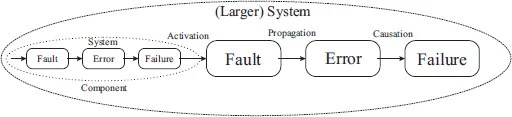

1.1.2 Threat Models

- ◾ Based on the source of the faults, faults can be classified as:

- – Hardware faults, if the faults are caused by the failure of hardware components such as power outages, hard drive failures, bad memory chips, etc.

- – Software faults, if the faults are caused by software bugs such as race conditions and no-boundary-checks for arrays.

- – Operator faults, if the faults are caused by the operator of the system, for example, misconfiguration, wrong upgrade procedures, etc.

- ◾ Based on the intent of the faults, faults can be classified as:

- – Non-malicious faults, if the faults are not caused by a person with malicious intent. For example, the naturally occurred hardware faults and some remnant software bugs such as race conditions are non-malicious faults.

- – Malicious faults, if the faults are caused by a person with intent to harm the system, for example, to deny services to legitimate clients or to compromise the integrity of the service. Malicious faults are often referred to as commission faults, or Byzantine faults [5].

- ◾ Based on the duration of the faults, faults can be classified as:

- – Transient faults, if such a fault is activated momentarily and becomes dormant again. For example, the race condition might often show up as transient fault because if the threads stop accessing the shared variable concurrently, the fault appears to have disappeared.

- – Permanent faults, if once a fault is activated, the fault stays activated unless the faulty component is repaired or the source of the fault is addressed. For example, a power outage is considered a permanent fault because unless the power is restored, a computer system will remain powered off. A specific permanent fault is the (process) crash fault. A segmentation fault could result in the crash of a process.

- ◾ Based on how a fault in a component reveals to other components in the system, faults can be classified as:

- – Content faults, if the values passed on to other components are wrong due to the faults. A faulty component may always pass on the same wrong values to other components, or it may return different values to different components that it interacts with. The latter is specifically modeled as Byzantine faults [5].

- – Timing faults, if the faulty component either returns a reply too early, or too late alter receiving a request from another component. An extreme case is when the faulty component stops responding at all (i.e., it takes infinite amount of time to return a reply), e.g., when the component crashes, or hangs due to an infinite loop or a deadlock.

- ◾ Based on whether or not a fault is reproducible or deterministic, faults (...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- References

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Logging and Checkpointing

- 3 Recovery-Oriented Computing

- 4 Data and Service Replication

- 5 Group Communication Systems

- 6 Consensus and the Paxos Algorithms

- 7 Byzantine Fault Tolerance

- 8 Cryptocurrency and Blockchain

- 9 Consensus Algorithms for Blockchain

- 10 Blockchain Applications

- Index

- End User License Agreement