- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

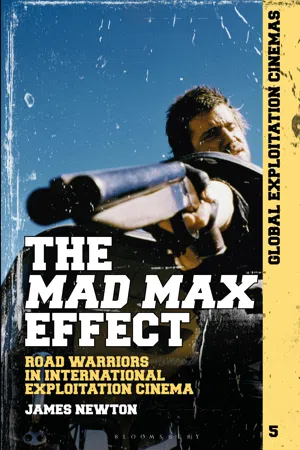

About this book

The Mad Max Effect provides an in-depth analysis of the Mad Max series, and how it began as an inventive concoction of

a number of influences from a range of exploitation genres (including the biker movie, the revenge film, and the car chase

cinema of the 1970s), to eventually inspiring a fresh cycle of international low budget 'road warrior' movies that appeared on home video in the 1980s. The Mad Max Effect is the first detailed academic study of the most famous and celebrated post-apocalypse film series, and

examines how a humble Australian action movie came from the cultural margins of exploitation cinema to have a profound impact on the broader media landscape.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Mad Max Effect by James Newton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Origins of the road warrior

The roots of the conventions, iconography and industrial machinations that characterize Mad Max, and the subsequent worldwide diaspora of MadMaxploitation, stretch back to before the proliferation of exploitation filmmaking that came after the break-up of the Hollywood studios in the 1960s. The elements are present in silent movies, particularly comedies that emphasize inventive stunts and slapstick and featuring stars such as Harold Lloyd and Larry Semon, as well as in Hot Rod movies from the 1950s, and in social problem films dealing with teenage delinquents. Within these three traditions there are themes, sequences and imagery that turn up later in George Miller’s series. There are also antecedents to be found in the western and in the broader grouping of the road movie (which themselves share themes).

More directly, the content and contexts associated with the series and those it influenced – warring biker gangs, futuristic dystopic wastelands and exploitation filmmaking from a spread of transnational countries – begin to take shape in the decade or so prior to the release of Mad Max in 1979. In the 1970s there was a convergence of exploitation traditions that crossed cultural and national boundaries of production and exhibition. Entire genres as well as individual films from one continent influenced filmmakers from other parts of the world. Films that required dubbing for translation, such as kung fu movies from Hong Kong, played to appreciative international audiences having overcome initial language barriers. Other films, notably those from Australia, would disguise their country of origin by playing down or removing geographical features and peculiarities so as to more readily translate to American audiences.

That this chapter ‘breaks out’ into a separate case study on the Death Race (1975–2017) films in Chapter 2 indicates the difficulty in explaining and containing all the relevant influences resulting in Mad Max. My task is a messy one and cannot be completed in a linear manner – such is the dispersal and spread of all the influences that Mad Max subsumed.1 So, for the purposes of space I have closed down the ‘prehistory’ of the series to three different but overlapping contexts. The first is what has been termed as ‘Ozploitation’, commercial genre filmmaking from Australia in the 1970s and 1980s. The second context is the cycle of biker movies that were principally American productions but whose impact can be seen in Australia and even Great Britain. The third is the prevalence of the revenge narrative in the cinema of the 1970s. There are, of course, multiple books, articles and chapters written about the biker movie and the revenge film, and also an expanding body of scholarship about Ozploitation. This chapter draws on some of these works in an effort to locate and explore the most germane parts for the Mad Max series and examines how the familiarity of the revenge story arc, combined with the burgeoning Australian production context and the aesthetic concerns of the biker film, meant that Mad Max was a concept that was sellable to international audiences. In part, its impact and global financial success was because it was immediately identifiable in terms of its constituent parts (as well as fitting in with ‘carsploitation’ and general dystopian science fiction of the era). Miller’s film uniquely combined these recognizable elements to create a product that was at once identifiable and yet also alien enough as to appear fresh.

In relation to the low-budget production cycles of the 1950s, Peter Stanfield writes that ‘tracking the dialectic between repetition and innovation across runs of films makes legible changes to cinematic environments and the public sphere within which films are produced and consumed’ (Stanfield 2015: 6). By digging into the ‘prehistory’ of Mad Max, this chapter begins a similar process, continued throughout this book, of examining some of the repetitions and innovations that led to Miller’s series and the subsequent cycle it helped to inspire in the 1980s. This chapter begins the process of tracing and identifying some of the through-lines and continuities of exploitation film culture from the 1960s to the present day. It is a process that will be repeated in Chapter 5, where I track the ‘repetitions’ and ‘innovations’ of MadMaxploitation. This chapter begins a methodological journey that will only be completed by the end of the book and addresses the central question: what was the topography of exploitation and genre cinema into which Mad Max was born?

The Australian context and ‘Ozploitation’

In his Film News article from 1979, James Ricketson reflected on the unease that surrounded the notion of ‘Ozploitation’, the section of the nation’s film history that most resembled the supposedly low art exploitation cinemas of other countries. In posing the question as to what was wanted from an Australian Film Industry, he asked whether it should be based on an organic, indigenous or ‘authentic’ Australia, or to settle for the commercial export model of Ozploitation, which involved producing what he saw as ‘second-rate replicas’ that mimicked the ‘cinematic models and language’ of Hollywood (Ricketson 1985: 223).

Stuart Cunningham identifies this as an ‘opposition’ between culture and industry that parallels the split between art cinema and commercial film production (1985: 235). Australian cinema that sat on the culture/art side of the dividing line ‘invited pleasure in the epiphanous moment of the reverently registered gesture, intonation, accent, slang, landscape, décor or attitude that betokened Australian-ness’ (1985: 235). They were, he writes, ‘quiet films’ (1985: 235). The government funding bodies that existed to encourage such productions were the ‘Australian equivalent to Hollywood studios’ according to Moran and Vieth (2006: 132), because they were the gatekeepers in terms of funding and in the scope of each project.

One consequence of such gatekeeping in the Australian film industry was the ‘destructive force’ of the documentary unit Film Australia that Stephen Wallace claimed in the mid-1970s was affecting the output of its national cinema and had failed to ‘permit the making and releasing of films of any independence of mind or spirit’ ([1976] 1985: 122). Among the negative effects of Film Australia’s conservatism was the ‘stifling’ of explicit political or social comment, other than those that endorsed government policy, and the suppression of experimentation, ‘personality’ or individual bias in the documentaries it was set up to nurture ([1976] 1985: 123). This led to the marginalization of working-class subjects and films reflecting social reality or problems. It was, according to Wallace, ‘a middle-class propaganda machine’ ([1976] 1985: 126). Such middle-classness was characteristic of the desire for ‘respectable’ cinematic output in fiction films of the same period. The move towards the more commercial ‘Ozploitation’ that was happening around the time of Wallace’s lament at least broke down this middle-classness and brought to the fore social concerns, even if it was only in the narratives of biker gangs or ‘ockers’ – a pejorative term for supposedly uncultured, uncivilized or vulgar working-class Australian men.

Jonathan Rayner writes that the national cinema output of Australia ‘epitomises the difficult relationships’ that ‘smaller film industries enjoy with Hollywood’, with which they are inspired by and most often unsuccessfully try to mimic (Rayner 2000b: 3). The commercial films being produced, Ozploitation among them, were an essential part of what is known as the Australian Revival of the 1970s and not only contributed to the increasing opportunities for production but also attained sporadic success abroad. That Australian cinema was seen by the government as a vehicle to help cement a ‘national brand’ meant that Ozploitation was, by contrast, ‘critically dismissed’ according to Alexandra Heller-Nicholas (2016: 163) because it was damaging to such branding. Ozploitation was also considered a bastardized cinema through its reliance on influences from America. Characterized by an emphasis on ‘excess, spectacle, and sensation’ (Heller-Nicholas 2016: 170), Ozploitation comprised of ‘influences similar to those that permeated the US grindhouse circuit, from rape-revenge to slasher, martial arts to sexploitation’ (2016: 164). It should be emphasized that these influences, which resulted in the disparate waves, cycles and genres playing in US grindhouses, did not always comprise American-made films and instead would have originated in many transnational cinemas. In 42nd Street grindhouse theatres at the time of Mad Max’s New York release, for example, over a third of the programming comprised of non-American productions (Filibus 2018). Ozploitation in this regard was influenced by an international cinematic culture, but one that was grouped together into the single environment of US theatrical distribution, rather than by specifically American films.

The term ‘Ozploitation’ itself is a relatively recent one and originates from Mark Hartley’s 2008 movie Not Quite Hollywood. This feature-length documentary ‘spearheaded’ (Heller-Nicholas 2016: 164) the resurgence of attention on genre filmmaking from Australia. Not Quite Hollywood is the moment which reconcentrates focus on this neglected area of film history and, as Heller-Nicholas notes, invented the portmanteau term ‘Ozploitation’ to group together the disparate titles. Like ‘Film Noir’, then, Ozploitation is a retrofitted body of work, so named many years after it existed. Not Quite Hollywood establishes the parameters for the beginning of discussions on what is Ozploitation and what it means for the history of Australian culture, as well as for exploitation cinema more broadly. Part of the pleasure in Hartley’s film is once again enjoying the sensationalism of Ozploitation, and the film reconstitutes the violence, stunts and nudity for a new audience previously unfamiliar with exploitation product from Australia. With this in mind, it works as not only a document of the period, and as a collection of amusing and insightful anecdotes from those responsible for making the movies, but also an example of Australian exploitation itself. It is both a documentary about Ozploitation as well as being a recent example of the tradition.

Heller-Nicholas makes the point that the title of Not Quite Hollywood ‘speaks to a stream of national production that is defined by the tensions governing transnational flows’ (2016: 168). These questions permeate the discourse around international exploitation culture, where there is a continual series of conflicts and tensions between local production and international marketplaces, and where cultural specificities such as Chinese kung fu, American muscle cars or anxieties over the perceived urban hell provoked by New York City’s crime rate found popularity with foreign audiences around the world. This popularity would often be reflected by countries producing their own versions of these cycles, resulting in American martial arts pictures or New York urban hell narratives made by European industries, such as Lucio Fulci’s New York Ripper (1980). Another example of the convergence across the various countries producing exploitation is Summer City (Christopher Fraser, 1977), Mel Gibson’s first movie, which transplants the brief US-based 1960s fascination with surfing and beach movies to Australia. These tensions are highlighted even further in those cases where there is also an attempt to hide regional production contexts. Films like Harlequin (Simon Wincer, 1980) deliberately obscure its Australian origins in a bid to appeal to international markets by depicting on screen ‘an Americanized political system, and the inclusions of right-hand-drive cars, American flags at political rallies, and even a Dixie band’ (Heller-Nicholas 2016: 175). Mad Max suffered a variation of this tendency to avoid seeming Australian, when its US distributors redubbed the cast into American accents. The global exploitation industries relied upon selling similar products to diverse markets, but these often came from dissimilar origins an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Origins of the road warrior

- 2 The Death Race lineage

- 3 Contextualizing Mad Max

- 4 Post-apocalypse now! The politics of Mad Max

- 5 MadMaxploitation! Transnational road warriors

- 6 Fury Road and the imitation of exploitation

- 7 Mad Max and the metatext: Fan engagement and online culture

- Conclusion: A few years from now

- Films Cited

- References

- Index

- Copyright Page