- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

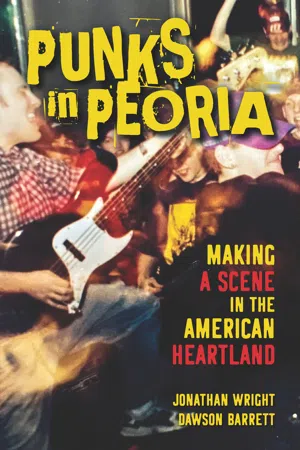

Punk rock culture in a preeminently average town

Synonymous with American mediocrity, Peoria was fertile ground for the boredom- and anger-fueled fury of punk rock. Jonathan Wright and Dawson Barrett explore the do-it-yourself scene built by Peoria punks, performers, and scenesters in the 1980s and 1990s. From fanzines to indie record shops to renting the VFW hall for an all-ages show, Peoria's punk culture reflected the movement elsewhere, but the city's conservatism and industrial decline offered a richer-than-usual target environment for rebellion. Eyewitness accounts take readers into hangouts and long-lost venues, while interviews with the people who were there trace the ever-changing scene and varied fortunes of local legends like Caustic Defiance, Dollface, and Planes Mistaken for Stars. What emerges is a sympathetic portrait of a youth culture in search of entertainment but just as hungry for community—the shared sense of otherness that, even for one night only, could unite outsiders and discontents under the banner of music.

Synonymous with American mediocrity, Peoria was fertile ground for the boredom- and anger-fueled fury of punk rock. Jonathan Wright and Dawson Barrett explore the do-it-yourself scene built by Peoria punks, performers, and scenesters in the 1980s and 1990s. From fanzines to indie record shops to renting the VFW hall for an all-ages show, Peoria's punk culture reflected the movement elsewhere, but the city's conservatism and industrial decline offered a richer-than-usual target environment for rebellion. Eyewitness accounts take readers into hangouts and long-lost venues, while interviews with the people who were there trace the ever-changing scene and varied fortunes of local legends like Caustic Defiance, Dollface, and Planes Mistaken for Stars. What emerges is a sympathetic portrait of a youth culture in search of entertainment but just as hungry for community—the shared sense of otherness that, even for one night only, could unite outsiders and discontents under the banner of music.

A raucous look at a small-city underground, Punks in Peoria takes readers off the beaten track to reveal the punk rock life as lived in Anytown, U.S.A.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Punks in Peoria by Jonathan Wright,Dawson Barrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780252052705Subtopic

Historia de NorteaméricaPART I

The Rise of Peoria Punk Rock:

1956–1986

1956–1986

As a midsized city in the rural, conservative Midwest, Peoria was an unlikely setting for a countercultural arts scene. Its proximity to Chicago and St. Louis, however, had long made it a convenient add-on date for entertainers of various stripes—a low-stakes proving ground for new material. During the 1960s and ’70s, Peoria was a regular stop for musical acts who needed dates in smaller cities to sustain their tours between bigger gigs. It was well steeped in rock and roll but mostly missed the punk rock wave of the late 1970s. Peoria’s connection to bands like the Ramones, the Clash, and the Sex Pistols was largely limited to a minute selection of albums at local record stores.

When a real punk scene finally emerged in Peoria in the mid-1980s, it was guided not by the comparatively listenable music of that earlier period but rather by hardcore—a new iteration of punk rock that was both more aggressive and more bluntly political. Just as DIY torchbearers like Minor Threat, Black Flag, and the Dead Kennedys flatly rejected corporate attempts to monetize punk, hardcore fans made their own magazines (“zines”), and bands put out records on their own labels and booked their own tours.1

Paralleling the rise of hip-hop during this period, hardcore bands also lashed out against the reactionary politics embodied by President Ronald Reagan. Flyers for early hardcore shows routinely featured anti-Reagan images, and in cities like San Francisco (home of the Dead Kennedys), Washington, DC (Minor Threat and the Bad Brains), and Los Angeles (Black Flag and the Circle Jerks), bands offered a broader political critique. In central Illinois, however, Reaganism was the well-accepted norm. Not only did the area vote overwhelmingly for the Reagan-Bush ticket, but “The Gipper” was an Illinois native and graduate of nearby Eureka College, just a twenty-minute drive from downtown Peoria.2

Peoria’s early punks were united less by politics—or even specific musical tastes—than by a broader disdain for mainstream culture. The Reagan Revolution, after all, represented much more than public policy. To the young people of the 1980s, it reflected the uptight conservatism of their grandparents’ generation—a throwback to the conformity, sexual repression, and unquestioning patriotism of the 1950s.

Peoria’s early punk scene was also far from monolithic, drawing influence from both the anti-drug, “straight-edge” Minor Threat and the shock rock of heavy metal pioneers like Black Sabbath and Alice Cooper. It began as just a handful of aspiring musicians and skateboarders. But within a few short years, Peoria’s punk rebellion was a veritable youth counterculture with its own social spaces and even its own unique slang terms.

CHAPTER 1

Heebie Mesolithic Eon Drizzle

Midwesterners were distinguished by their lack of distinguishing characteristics. Anything but flamboyant, they supposedly had no discernible accent or clothing or customs. Their culture, like their history and their landscape, was linear and straightforward, without major drama, without peaks or valleys.

—Richard Sisson, Christian Zacher, and Andre Cayton,

The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia

The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia

We all know that Illinois ain’t such hot shit, right? … In fact, about all the Land of Lincoln does have going for it is its all-star dirt, squoozed out of the bedrock by some heebie Mesolithic eon drizzle and laying there a few million years waiting for the first soybean seed.

—Rick Johnson Reader

It’s a working-class river town built on manufacturing and agriculture—the now-former home of Caterpillar’s world headquarters, an ancestral hub of midwestern vaudeville, and perpetual purveyor of the old phrase “Will it play in Peoria?” Musically speaking, Peoria, Illinois, may be best known as the hometown of soft-rock singer-songwriter Dan Fogelberg or REO Speedwagon guitarist Gary Richrath (of East Peoria, across the Illinois River). At times Peoria has seemed stuck in the past, depressingly static as a steady stream of bar bands served up watered-down imitations of Ted Nugent or Cheap Trick, rock and roll covers with a side of the blues. Artists whose work was not middle-of the-road—the city’s most talented native son, comedian Richard Pryor, for example—tended to be studiously ignored, if not ardently reproached. Such was the consequence of a deeply rooted heartland conservatism, a widespread lack of stomach for anything remotely “edgy,” and, in Pryor’s case at least, a formidable mountain of institutional racism.

Ever lagging behind the times, the self-described “Heart of Illinois” was certainly an unlikely incubator for the punk rock revolution slowly making its way inland in the 1980s. But rewind a few decades to the supposed peak years of the city’s cultural homogeny—to the early days of rock and roll—and the Peoria region had a lively and active music scene …

* * *

On February 7, 1957, the Peoria Journal Star made the announcement with deft alliteration: “Professional Presleyans Put On Peoria Premiere.” Despite the fears of parents across the nation, rock and roll had landed in middle America. A series of “shindigs”—Peoria’s “first public rock ’n’ roll dances”—were held at the Itoo Hall on South Adams Street, a gathering place for the city’s sizable Lebanese immigrant population. Admission to local impresario Bill Reardon’s “Teen-Age Frolics” (featuring “2 sensational rock-n-roll singers” and “a red hot 7 piece band”) was just ninety cents.1 Advertisements in the newspaper touted the unique events:

Dancing—entertainment country style …

Everyone invited!

No age limit

No intox. allowed.

Police protection.

Dancing starts 8 p.m.

Snack bar open.2

Everyone invited!

No age limit

No intox. allowed.

Police protection.

Dancing starts 8 p.m.

Snack bar open.2

Elvis mania had arrived one year earlier. By the fall of 1956, following the performer’s dazzling first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, hundreds of enthusiastic teenage admirers lined the block outside Peoria’s downtown Rialto Theater for a special matinee showing of Presley’s film debut, Love Me Tender. In a typical headline, the local newspaper questioned this new development: “Rock n’ Roll: Is It a Menace or Harmless Teen-Age Fun?” The same would be asked of subsequent generations—and their own musical innovations—in the years to come.3

In 1959, the Rockin’ R’s from the nearby village of Metamora, Illinois, took their swingin’ rockabilly rhythms all the way to Dick Clark’s American Bandstand on ABC-TV. The band’s hit instrumental, “The Beat,” spent eight weeks on the national charts and earned them gigs opening for their idols, Jerry Lee Lewis and Gene Vincent. They were eventually inducted into the Rockabilly Hall of Fame.4

The following year, another early pioneer of rock and roll settled in Peoria. Byron “Wild Child” Gipson was the lone African American in one of America’s first integrated rock bands, Freddie Tieken and the Rockers, from Quincy, Illinois. Prior to that, he had been a sideman and road manager for Little Richard. Wild Child was well acquainted with Peoria, having played many gigs at Harold’s Club, where an up-and-coming Richard Pryor polished his stand-up act in between sets. Gipson tore up Peoria stages throughout the sixties and would be a fixture on the local jazz and blues scene for decades.5

Though overshadowed by its proximity to Chicago, one of the world’s premier blues cities, Peoria was plentiful with blues talent of its own. Most prominently, Luther Allison enjoyed a decades-long musical career and was renowned for his soulful guitar work, even as he plugged away at day jobs in Peoria, working for Caterpillar and Keystone Steel and Wire. Both Eddie King and Emmett “Maestro” Sanders played guitar for Chicago’s “Queen of the Blues,” Koko Taylor, and both died relatively unheralded, overdue legacies buried amid their hometown’s underappreciated blues scene.

In the mid-sixties, teenage rock and roll bands like the Coachmen, the Wombats, and the Shags started popping up in Peoria-area garages, playing school dances, and battling it out in high school gymnasiums—just like everywhere else in the country. As the British Invasion gave way to the psychedelic era, local groups like Suburban 9 to 5, Abaddon, and Zimmo’s Thanatopsis began taking cues from Hendrix, Cream, and the Jefferson Airplane. Shaggy-haired teenagers were pushing the boundaries and remaking American culture for a new age.

The Kinks, the Hollies, the Yardbirds, and the Who were among the wave of prominent Brits who found their way across the Atlantic to play in Peoria. All four bands took the stage at Exposition Gardens, home of the Heart of Illinois Fair—that prototypical celebration of livestock competitions, amusement rides, and motor contests. With multiple buildings available for rent to the public, it was one of the area’s top concert venues, though the conservative Midwest was not an especially welcoming place for the emerging sixties counterculture.

The Kinks’ 1965 visit to Peoria, for example, was shaped by widespread aversion to the “long-haired British invaders,” including one frightening encounter with “a redneck punk who [drove] the band around for the promoter, brandishing a gun in the process.”6 The incident left such an impression on Kinks singer Ray Davies that he recounted the anecdote in both his 1995 autobiography and his subsequent stage show.

Three years later, the Strawberry Alarm Clock found their Expo Gardens concert canceled following a midnight-hour raid on their East Peoria hotel room. All five members of the California band were arrested, and two were charged with drug possession. In Peoria, the scandal was front-page news. But when a prominent San Francisco attorney flew into town to advocate for the musicians—claiming they were framed by local authorities hostile to their long hair and hippie attire—the charges were dropped.7

In September 1967, the Doors managed to avoid arrest when they played a high school gymnasium in the small town of Canton, about thirty miles southwest of Peoria, just four days before their notorious Ed Sullivan debut. While “Light My Fire” hit the top of the charts that summer, the band “came and went with almost no fanfare, noticed mostly for their long hair in a conservative burg still struggling with widespread cultural change.”8

When the Who took the stage at Expo Gardens on March 10, 1968, a BBC crew was on hand filming a documentary about popular music that examined the revolutionary possibilities of rock and roll at a time when cultural revolution was very much in the air. To this day, footage of Pete Townsend and bandmates trashing their gear after a particularly scorching rendering of “My Generation” remains a touchstone of Peoria musical lore. But the Who’s three-hour late arrival angered promoter Hank Skinner, who refused to pay the remainder of their $1,500 guarantee—and the band was not happy about it. “They wanted their $750!” exclaims Craig Moore, frontman of Iowa garage-rock legends GONN, Ilmo Smokehouse, and a string of other bands, who moved to Peoria in the mid-seventies and became an agent for Skinner’s Peoria Musical Enterprises. “[Hank] told them … to pack up their shit and get out.”9 The promoter allegedly swiped Pete Townsend’s white Beatle boots before running the band out of town—notwithstanding Townsend’s threats of legal action, which ultimately proved hollow.

Incidentally, two of the local acts that opened for the Who at Expo Gardens—Suburban 9 to 5 and the Coachmen—counted among their ranks Gary Richrath and Dan Fogelberg, respectively. Three years later, when Black Sabbath played the same room, it was Richrath’s REO Speedwagon that opened the show—the hometown boy making good.10

Across town in the pre–rock and roll era, a large horse stable on the northern outskirts of Peori...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. The Rise of Peoria Punk Rock: 1956–1986

- Part II. Building the Scene: 1986–1992

- Part III. The Next Nirvana: 1992–1997

- Part IV. Tolling of the Digital Bell: 1997–2007

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover