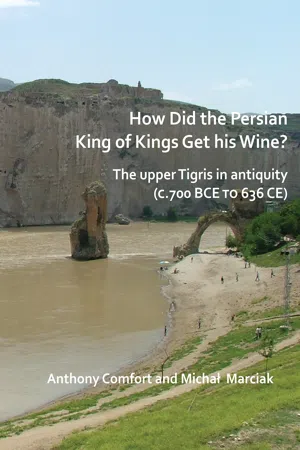

How did the Persian King of Kings Get His Wine? The upper Tigris in antiquity (c.700 BCE to 636 CE)

- 156 pages

- English

- PDF

- Available on iOS & Android

How did the Persian King of Kings Get His Wine? The upper Tigris in antiquity (c.700 BCE to 636 CE)

About this book

How did the Persian King of Kings Get His Wine? the upper Tigris in antiquity (c.700 BCE to 636 CE)' explores the upper valley of the Tigris during antiquity. The area is little known to scholarship, and study is currently handicapped by the security situation in southeast Turkey and by the completion during 2018 of the Il?su dam. The reservoir being created will drown a large part of the valley and will destroy many archaeological sites, some of which have not been investigated. The course of the upper Tigris discussed here is the section from Mosul up to its source north of Diyarbak?r; the monograph describes the history of the river valley from the end of the Late Assyrian empire through to the Arab conquests, thus including the conflicts between Rome and Persia. It considers the transport network by river and road and provides an assessment of the damage to cultural heritage caused both by the Saddam dam (also known as the Eski Mosul dam) in Iraq and by the Il?su dam in south-east Turkey. A catalogue describes the sites important during the long period under review in and around the valley. During the period reviewed this area was strategically important for Assyria's relations with its northern neighbours, for the Hellenistic world's relations with Persia and for Roman relations with first the kingdom of Parthia and then with Sassanian Persia.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents Page

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- A. Figure 1

- B. Figure 2

- D. Figure 4

- c. Figure 3

- E. Figure 5

- F. Figure 6

- Transport and the road network

- Relief sculptures

- Figure 8 Drawing of the rider relief by Layard, 1850; reproduced in Reade and Anderson 2013 © Trustees of the British Museum

- Figure 7 Photos: Land of Nineveh project (http://www.terradininive.com – Photogallery)

- Figure 9a and b The rider relief

- Figure 10 Khinis

- Figure 11 Suggested reconstruction of rider relief by Reade (fig 59) for the period 100 BCE to 100 CE

- Figure 12

- Figure 13 Fenik Parthian relief

- Figure 14 Inlı Çay Parthian relief

- Figure 15 Boşat Parthian/Sassanian relief

- Figure 16 Eğil Late Assyrian relief Photo: Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

- Figure 17 Hilar Possibly Parthian or classical period relief

- Dams on the upper Tigris and their consequences for historic monuments

- Catalogue

- Sites from antiquity (700 BCE to 636 CE) on and around the upper Tigris

- Figure 18 The bridge at Mosul at the end of the nineteenth century

- Figure 19 Western Adiabene, Hatra, and the Roman frontier

- Figure 20 Map showing the position of the monasteries around Mosul/Nineveh

- Figure 21 Eski Mosul

- Figure 22 Seh Qubba

- Figure 23 Extract from anonymous hand-drawn ‘Map of Roman Limes Defences and Roads in Iraq and Syria, from surveys of Sir Aurel Stein 1939 and other sources’; used as a source by David Kennedy for the map published at end of Gregory 1985: Vol1

- Figure 24 The road on the east bank opposite Abu Dhahir

- Figure 25 Satellite image showing relative position of sites mentioned

- Figure 26 Satellite image of Feshkhabur

- Figure 27. Bell photo of castle at Zakho – extract of M_057_07

- Figure 28 Drawing in Maunsell, 1889

- Figure 29 Pir Delal photo: Anthony Comfort

- Figure 30 Stein’s photo of the Kuzaf bridge on the Haizil river north of Zakho British Library Photo 392/41(12)

- Figure 31 Basorin Zoom Earth/Bing

- Figure 32a Shakh – situation

- Figure 32b Detail of Fig a showing Shakh town

- Figure 33 The bridge over the ditch

- Figure 34 Extract from Peutinger Table

- Figure 35a The Kazrik gorge from the north

- Figure 35b The east bank fort at the Kasrik gorge

- Figure 36. Kasrik gorge and Dera

- Figure 37 Upper Dera/Zarnuqa

- Figure 38 The ‘abandoned town’ (Lower Dera/Hlahlah?): interpretation AC

- Figure 39 One of the peaks above Fenik

- Figure 40 Hendek/Bezabde from Fenik

- Figure 41 A tower in the wall of Bezabde (Hendek)

- Figure 42 a) ‘Asurkalesi’, west of Damlarca/Fenik and b),c),d) other possible early fortresses west of Fenik Google Earth 15/04/2015, except c)

- Figure 43 Tower south of Güclükonak

- Figure 44 View looking SW from the road climbing to the plateau; promontory of Sulak to right

- Figure 45 a, b, c, d Three hans and a bridge in the Tigris/Bohtan valley

- Figure 46 Tilli/Cattepe

- Figure 47 Redvan/Başari

- Figure 48 Stone structure at Arzen

- Figure 49 Zercel Kale

- Figure 50 Extract from Google Earth (6/4/2017) to illustrate Chlomaron/Kulimmeri discussion

- Figure 51 Artukid bridge at Hasankeyf

- Figure 52 The ‘citadel’ of Hasankeyf

- Figure 53 Ancient tower in the city wall, Silvan

- Figure 54 Bridge at Köprüköy, east of Bismil

- Figure 55 City walls of Amida

- Figure 56a Eğil citadel

- Figure 56b The Royal Tombs at Egil

- Figure 57 Dibne/Solali bridge

- Figure 58 The Dibne resurgence at Birkleyin

- Figure 59a ‘Sunken city’ of lake Hazar

- Figure 59b Satellite image of sunken city with enhancement;

- Acknowledgements

- Conclusion

- Bibliography