![]()

Part One

THE HEAD

Why peak oil and climate change mean that small is inevitable

“It is quite likely that the time interval before the global peak occurs will be briefer than the period required for societies to adapt themselves painlessly to a different energy regime.”– Richard Heinberg1

“Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius – and a lot of courage – to move in the opposite direction.” – Albert Einstein

“I feel it is my duty, given the social and economic chaos peak oil will undoubtedly produce, to stick very closely to defensible assumptions. If you ask me whether I personally think we’ll make it to 2010, my answer is ‘probably not’. Random factors and Murphy’s Law more or less rule out everything running smoothly. This however is not analysis, but gut feel and hunch. On the hunch basis 2008 would be my answer, but 2010 my analysis.” – Chris Skrebowski2

We live in momentous times: times when change is accelerating, and when the horror of what could happen if we do nothing and the brilliance of what we could achieve if we act can both, at times, be overwhelming. This book is underpinned by one simple premise: that the end of what we might call The Age of Cheap Oil (which lasted from 1859 until the present) is near at hand, and that for a society utterly dependent on it, this means enormous change; but that the future with less oil could be preferable to the present, if we plan sufficiently in advance with imagination and creativity.

This first part is called ‘The Head’ because it focuses on the concepts and issues central to the case that we need to be preparing for a future which looks very different from the present. It begins with an exploration of peak oil and climate change, the twin drivers of the Transition concept and the two greatest challenges facing humanity at the beginning of the 21st century (heading a long field of competitors). I will attempt to cover them in as accessible a way as possible. It goes on to set out the nature of the challenges they present, and why they so urgently necessitate our rethinking a number of very basic assumptions as well as the scale at which we operate. Peak oil is dealt with first, and in more detail, because the likelihood is that you are less familiar with it. While climate change features widely in the media, peak oil has yet to register as a major issue, although the recent steep rises in prices are starting to change this. It is important to get up to speed on an issue of such central importance to our future.

I will go on to look at what kind of a world we could end up with if we don’t respond imaginatively to these dual challenges, and then set out the thinking and the concepts underpinning Transition Initiatives. These initiatives are an emerging response: in essence, a powerful carbon reduction ‘technology’ and a new way of looking at responding to climate change and peak oil. They will be explored in depth as this book goes on.

![]()

Chapter 1

Peak oil and climate change

The two great oversights of our times3

“Sometime in 2006, mankind’s thirst for oil will have crossed the milestone rate of 86 million barrels per day, which translates into a staggering 1,000 barrels a second! Picture an Olympic-sized swimming pool full of oil: we would drain it in about 15 seconds. In one day, we empty close to 5,500 such swimming pools.”

– Peter Tertzakian (2006),

A Thousand Barrels a Second:

the coming oil break point and

the challenges facing an

energy-dependent world,

McGraw Hill

What is peak oil?: why it isn’t the last drop that matters

There are plenty of other people better qualified than myself to tell you about peak oil.4 I have never worked in the oil industry, am not a geologist, and other than having grown up in what is now one of the most rapidly depleting oil-producing nations in the world (the UK), I have no first-hand experience of oil production or geology. Prior to September 2004 I had never heard of the concept of peak oil, and had always assumed that oil in our economy worked in the same way as petrol in the tank of a car; that whether the engine was full or almost empty, it would run exactly the same. I thought we would potter along until some day in the distant future someone would put the very last drop of oil in their car and that would be that, a bit like the last truffula tree falling in Dr Seuss’s The Lorax.5 I was later to discover that I was somewhat wide of the mark, as I started to delve deeper into this incredibly important subject.

For me, learning about peak oil has been profoundly illuminating in terms of how I see the world and the way it works: the precarious nature of what we have come to see as how a society should function, as well as elements that any community responses we develop will need to have. Don’t take my word for it – read around, inform yourself. Climate change – an issue of great severity – is only one half of the story; developing an understanding of peak oil is similarly essential. Together, these two issues have been referred to as the ‘Hydrocarbon Twins’. They are so intertwined, that seen in isolation, a large part of the story remains untold.

Without cheap oil, you wouldn’t be reading this book now. The centralised distribution of books would not have been feasible, and if you did have a copy, it would be one of only a very few books you had, and you would consider it a very precious possession indeed. I would not have been able to type it on my laptop, in a warm house, listening to CDs. When you really start thinking about it, it’s not just this book that would not be here. Most things around you rely on cheap oil for their manufacture and transportation. Your furniture, entertainment, recreation, food, household appliances, medicines and cosmetics are all dependent on this miraculous material. This is not a criticism – it’s just how it is for us all, and has been for as long as most of us can remember. It is almost impossible to imagine anything else.

It is entirely understandable how we got into this position. Oil is a remarkable substance. It was formed from prehistoric zooplankton and algae that covered the oceans 90-150 million years ago, ironically during two periods of global warming. It sank to the bottom of the ocean, was covered by sediment washed in from surrounding land, buried deeper and deeper, and over time was heated under extreme pressure by geological processes, and eventually became oil.6 Natural gas was formed through similar processes, but is formed more from vegetal remains or from oil that became ‘overcooked’ when buried too deep in the Earth’s crust. One gallon of oil contains the equivalent of about 98 tons of the original surface-forming, algal matter, distilled over millennia, and which had itself collected enormous amounts of solar energy on the waves of the prehistoric ocean.7 It is not for nothing that fossil fuels are sometimes referred to as ‘ancient sunlight’. They are astonishingly energy-dense.

I like to think of fossil fuels being like the magic potion in Asterix and Obelix books. Goscinny and Uderzo’s Gaulish heroes live in the only village to hold out against Roman occupation, thanks to a magic potion brewed to a secret recipe by their druid, Getafix. The potion gives them superhuman strength and makes them invincible, much to the chagrin of Julius Caesar. Like Asterix and Obelix’s magic potion, oil makes us far stronger, faster and more productive than we have ever been, enabling our society to do between 70 and 100 times more work than would be possible without it.8 We have lived with this potion for 150 years and, like Asterix and Obelix, have got used to thinking we will always have it, indeed we have designed our living arrangements in such a way as to be entirely dependent on it.

It is estimated that 40 litres of petrol in the tank of a car contains energy equivalent to 4 years human manual labour.9 It is no wonder that we in the West consume on average about 16 barrels of oil a year per capita – less than Kuwait, where they use 36 (what do they do, bathe in it?), but far more than China’s two, or India’s less than one.10 The amount of energy needed to maintain the average US citizen is the equivalent of 50 people on bicycles pedalling furiously in our back gardens day and night.11 We have become dependent on these pedallers – what some people refer to as ‘energy slaves’.12 But we are, it should also be acknowledged, extremely fortunate to live at a time in history with access to amounts of energy and a range of materials, products and possibilities that our ancestors couldn’t even have imagined.

A FEW OF THE THINGS IN OUR HOMES MADE FROM OIL

Aspirins, sticky tape, trainer shoes, lycra socks, glue, paints, varnish, foam mattresses, carpets, nylon, polyester, CDs, DVDs, plastic bottles, contact lenses, hair gel, brushes, toothbrushes, rubber gloves, washing-up bowls, electric sockets, plugs, shoe polish, furniture wax, computers, printers, candles, bags, coats, bubble wrap, bicycle pumps, fruit juice containers, rawlplugs, credit cards, loft insulation, PVC windows, shopping bags, lipstick … and that’s just some of the things made directly from oil, not those that needed fossil fuels and the energy they consume in their manufacture (which is pretty much everything).

“What is remarkable is the failure of politicians to start planning in any way for this inevitable transition, or even to start preparing their electorates for its inevitability.”

– Jonathan Porritt (2007),

Capitalism as if the Earth Matters,

Earthscan

“Peak oil is a turning point in history of unparalleled magnitude, for never before has a resource as critical as oil become headed into decline from natural depletion without sight of a better substitute.”

– Colin Campbell

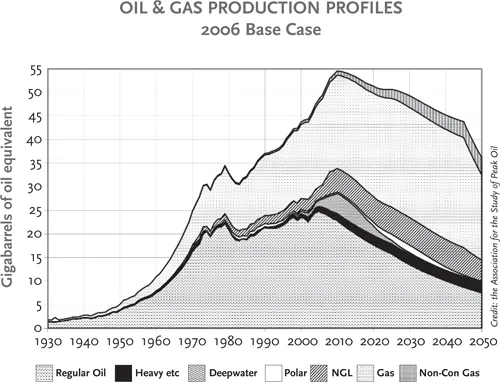

Figure 1. A Map of the Petroleum Interval. The Association for the Study of Peak Oil’s graph of cumulative oil and gas production, which is one of the best researched maps of the possible future of oil and gas production.

Figure 1 presents one of the best researched graphic representations of what we might call the ‘The Petroleum Interval’,13 the brief interlude of 200 years where we extracted all of this amazing material from the ground and burnt it. Viewed in the historical context of thousands of years, it is a brief spike. Viewed from where we stand now, it looks like the top of a mountain.

Oil has allowed us to create extraordinary technologies, cultures and discoveries, to set foot on the Moon and to perfect the Pop Tart. But can it go on forever? Of course not. Like any finite material, the faster we consume it, the faster it will be gone. We are like Asterix and Obelix realising, with a sinking feeling in the pit of the stomach, that the cauldron of potion they have in front of them is the last one. We can see the possibility of life without potion looming before us.

The key point here is that it is not the point when we use the last drop that matters. The moment that really matters is the peak, the moment when you realise that from that point onward there will always be less magic potion year-on-year, and that because of its increasing scarcity, it will become an increasingly expensive commodity. This year (2008), oil has for the first time broken through the $100 a barrel ceiling. Chris Skrebowski, editor of Petroleum Review magazine, defines peak oil thus, “the point when further expansion of oil production becomes impossible because new production flows are fully offset by production declines”.14 It is the midway point – the moment when half of the reserves have been used up, sometimes referred to as ‘peak oil’ or the ‘tipping point’ that is important. It is a moment of historic importance. All the way up the slope towards the peak, since Drake drilled the first...