![]()

Part One

CULTURAL STORIES AND VISIONS OF THE FUTURE

![]()

Chapter 1

Why cultural stories matter

On the previous two pages I outlined the trends on climate change and peak oil, which represent perhaps the most urgent and significant forces shaping our future. Yet even these challenges are, in a sense, only symptoms of an underlying reality. They are consequences of the choices we have collectively made and continue to make, and these choices are shaped by our understanding of the world – by our stories.

It is the stories that we tell ourselves about life – both individually and in our wider cultures – that allow us to make sense of the bewildering array of sensory experiences and wider evidence that we encounter. They tell us what is important, and they shape our perceptions and thoughts. This is why we use fairy stories to educate our children, why advertisers pay such extraordinary sums to present their perspectives, and why politicians present both positive and negative visions and narratives to win our votes.7

Totnes poet Matt Harvey telling stories at the launch of the town’s EDAP process

Our cultural stories help to define who we are and they strongly impact our behaviours. One example of a dominant story in our present culture is that of ‘progress’ – the story that we currently live in one of the most advanced civilisations the world has ever known, and that we are advancing further and faster all the time. The definition of ‘advancement’ is vague – though tied in with concepts like scientific and technological progress – but the story is powerfully held. And if we hold to this cultural story then ‘business as usual’ is an attractive prospect – a continuation of this astonishing advancement.

“A person will worship something, have no doubt about that. We may think our tribute is paid in secret in the dark recesses of our hearts, but it will out. That which dominates our imaginations and our thoughts will determine our lives, and our character. Therefore, it behooves us to be careful what we worship, for what we are worshipping we are becoming.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

“When people treat, say, fizzy brown sugar water as a source of their identity and human value, their resemblance to fairy-tale characters under an enchantment isn’t accidental.”

– John Michael Greer

The problem with stories comes when they shape our thinking in ways that do not reflect reality and yet we refuse to change them. The evidence might support the view that this ‘advanced’ culture is not making us happy and is rapidly destroying our environment’s ability to support us, but dominant cultural stories are powerful things, and those who challenge them tend to meet resistance and even ridicule.

The developing physical realities examined in detail in Parts Four and Five will surely change our cultural stories, whether we like it or not, but we can choose whether to actively engage with this process or to simply be subject to it.

The powerful cultural story that ‘real change is impossible’ makes it seem inevitable that current trends will continue inexorably on, yet in reality cultural stories are always shifting and changing, often subtly, but sometimes dramatically. Given their importance, then, we should pay close attention when Sharon Astyk suggests that there are certain key historical moments at which it is possible to reshape cultural stories rapidly and dramatically, by advancing one’s agenda as a logical response to events:

“I think it is true that had Americans been told after 9/11, ‘We want you to go out and grow a victory garden and cut back on energy usage’, the response would have been tremendous – it would absolutely have been possible to harness the anger and pain and frustration of those moments, and a people who desperately wanted something to do.” 8

As Naomi Klein has argued in her book Shock Doctrine, this insight has until now mostly been used to advance cultural stories that benefit a few at the expense of many. Astyk contends, however, that there is no reason why, as understanding continues to spread, we could not grasp the next ‘threshold moment’ and build a dominant narrative linking it to the energy and climate context (to which it will almost inevitably be related), and explaining how this demands changes in our own attitudes and lifestyles.9

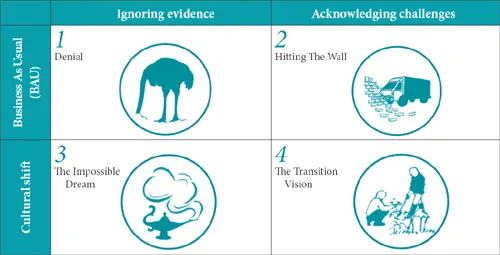

As we now look to our future, there are clearly a vast number of possibilities, but the concept of stories can help us to make some sense of it all. Here we will examine four visions of how our near-future could look, in the full awareness that the stories we tell here are themselves helping to shape the future that will come to pass.

“In a time of drastic change it is the learners who survive; the ‘learned’ find themselves fully equipped to live in a world that no longer exists.”

– Eric Hoffer

“Once we lived with a sense of our own limits. We may have been a hubristic kind of animal, but we knew that our precocity was contained within a universe that was overwhelmingly beyond our influence. That sensibility is about to return. Along with it will come a sense of frustration at finding many expectations dashed.”

– Richard Heinberg (2008), ‘Losing Control’, Post Carbon Institute

Visions of the future – looking to 2027

The first vision considers the continuation of the ‘business as usual, things can’t really be that bad’ perspective that is perhaps still dominant at this time, and where it is likely to lead us. In this vision the accumulating evidence on energy resource depletion and climate change is largely ignored. I have called this vision of the future Denial.

Our second vision of the future explores what might happen if we collectively accept the challenging evidence emerging on resource depletion and climate change, but continue working to address it through a business-as-usual mindset. We consider what happens when ‘politically realistic’ actions and scientific reality collide. I have called it Hitting The Wall.

Our third vision documents a radical change in the cultural stories shaping our present and future. Here we see a ‘cultural tipping point’ as the evidence of our eyes and hearts overthrows the dominant story of ‘business as usual’ and replaces it with a story of taking deep satisfaction in repairing earlier mistakes, and a responsible focus on ensuring a long-term resilient future. Nonetheless, in this vision we fail to acknowledge the scale of our energy and climate challenges, meaning that while we may appear to be building a brighter future we are in essence living an Impossible Dream.

Our final vision of the future is the one on which we will be focusing. Here we make the same kind of cultural shift as in vision #3, but with full regard to the overwhelming urgency of the ‘Peak Climate’ situation. I have called this The Transition Vision and it will be examined in more detail in Part Two.

“If you don’t know where you’re going, you’ll wind up someplace else.”

– Yogi Berra

![]()

Chapter 2

Vision 1: Denial

Business as usual/ignoring evidence

“If you don’t change direction, you are likely to end up where you’re headed.”

– Chinese proverb

“We have only two modes – complacency and panic.”

– James R. Schlesinger, the first US Dept. of Energy secretary, on the country’s approach to energy (1977)

In this possible future we failed to heed the ever-stronger e...