This book is available to read until 10th December, 2025

- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 10 Dec |Learn more

About this book

How can we reshape our economic system so that it will meet the needs of people and the Earth in the 21st century? In this Briefing, James Robertson outlines measures for building a healthier and more equal world. He identifies key ways in which people can work together to transform the economics of food and farming, work and livelihoods, local development, travel and transport, energy, technology and international trade.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Transforming Economic Life by James Robertson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

TRANSFORMING THE SYSTEM

“An economic system is not only an institutional device for satisfying existing wants and needs but a way of fashioning wants in the future.”

John Rawls 1

Principles

Today’s economic system must be transformed into a 21st-century economy “as if people and the Earth matter”.2 Many people see this transformation as one aspect of a larger historical change—the end of the modern age and the transition to a post-modern age, marked by a new awareness of our common humanity and our kinship with the rest of creation.

The principles underlying it will contrast with the principles of conventional economics today. They will include the following:

• systematic empowerment of people, as opposed to making and keeping them dependent;

• systematic conservation of resources and environment;

• evolution from a ‘wealth of nations’ model of economic life to a one-world model, and from today’s international economy to a decentralising multi-level one-world economic system;

• restoration of political and ethical choice to a central place in economic life and thought, based on respect for qualitative values, not just quantitative ones; and

• respect for feminine values, not just masculine ones.

Our approach must be based on action—to create a better future for people and the Earth. Economics cannot avoid being normative. Nature abhors a vacuum, and the vacuum created by the pretensions of conventional economics to be an objective, value-free science has been filled by values of power and greed.

In contrast to 20th-century economic orthodoxy, the 21st-century economy must be based on a realistic view of human nature. People are altruistic as well as selfish, co-operative as well as competitive. R.H. Tawney’s argument, that economic institutions should reward socially benign activities and so make the better choice the easier choice, makes sense. (But we should not dream, in Gandhi’s words, of systems so perfect that no-one will need to be good.)

Our perspective should be dynamic and developmental, not static. Our task is to change the direction of progress, not to achieve a permanent destination or lay out a blueprint for a once-for-all 21stcentury Utopia.

The State, the Market and the Citizen

There is not, never has been, nor ever could be, a completely free market economy. If an economy started by being wholly unregulated, some people would soon become powerful enough to destroy the freedom of others, and the free market would quickly become unfree. On the other hand, economies subject to detailed intervention by government soon become inefficient and corrupt. What is needed is a market economy operating freely within a well-designed framework of government, law and money (including taxes and public spending). By that framework, and how it influences prices throughout the economy, the state should aim to bring economic activity into harmony with society’s values.

So, what should the framework be designed to achieve? The answer is: it should empower and encourage people, communities, and nations to take more control over their own economic destinies, to become more economically self-reliant, and to live in ways that are environmentally benign. The changes this requires include changes of relationship between state, market and citizen.

Twentieth-century political debate and conflict has focused around three types of economy:

• a state-centred command economy;

• a business-centred free-market economy; and

• a mixed economy, in which economic power and influence are shared between government, business and trade unions—the ‘social partners’, in the idiom of continental Europe.

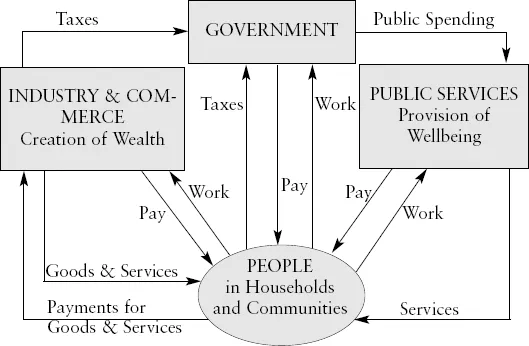

As suggested in Diagrams 1 and 2, all these have been based on a producer-centred, employer-centred model of the economic system,Transforming the System 17 which differs crucially from the people-centred (or citizen-centred) model needed for the 21st century.

Diagram 1

THE BIG BROTHER ECONOMY

THE BIG BROTHER ECONOMY

The collapse of communism is not “the end of history” and the start of permanent rule by conventional free-market capitalism. The reverse is true. Removal of the threat of Soviet state-dominated communism means that the non-communist world need no longer, in Hilaire Belloc’s words, “keep a-hold of Nurse for fear of finding something worse”. Future historians will see the collapse of communism as the first of two major changes that brought the producer-orientated economic development of the late modern era to an end. It opens the way to the transformation of Western businessdominated capitalism too.

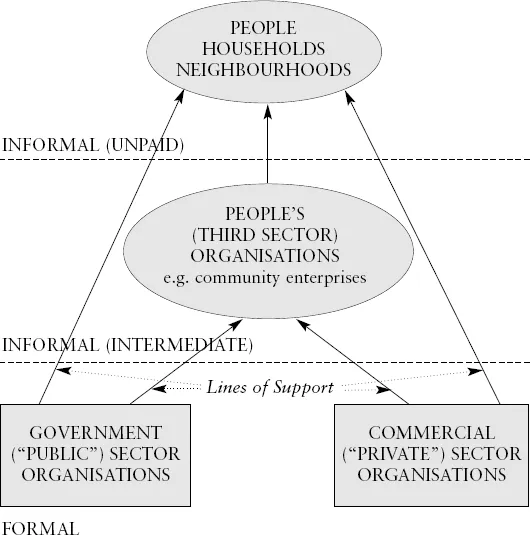

Market and state will both continue to play vital parts in a peoplecentred economy. But activities carried out neither for profit in the market nor by employees of the state will also help to shape economic and social progress in the 21st century. A growing informal economy, based on unpaid, interpersonal co-operative self-reliance, will be supported by a growing third sector of non-profit, non-state organisations distinct from the conventional “public” and “private” sectors. The province of citizen activity, free from the impersonal constraints of the state and the market under conventional communism/socialism and capitalism, will grow. The 20th-century economy has given priority to the interests of business and finance, employers and trade unions, government and other organisations, assuming that people must depend on them as consumers and employees in a production-centred dependency culture (“I shop, therefore I am”, “I have a job, therefore I am”). 21st-century economic and social debate will go beyond the dependency culture. It will focus on the needs and rights and responsibilities of people as persons and citizens. Hence the significance of the proposed Citizen’s Income.

Diagram 2

A PEOPLE-CENTRED ECONOMY

A PEOPLE-CENTRED ECONOMY

The Need For A Systemic Approach

A comprehensive transformation of economic life and thought will involve:

• every sector, such as farming and food, travel and transport, and others discussed in Chapter 2;

• every level: personal and household, neighbourhood and local community, district and city, regional (sub-national), national, continental and global; and

• every feature—such as lifestyle choices and values, technological innovation, governmental and other organisational goals and policies, methods of measurement and valuation such as accounting, and the theoretical basis for economic teaching and research.

The web of interconnections, relationships and interactions between all of these can be understood as an ‘ecology of change’ and, conversely, an ‘ecology of inertia’. Change achieved in one area (e.g energy use, or how economic success is measured) will help to ease change in others (e.g. agriculture, or transport), and change frustrated in one will help to frustrate it in others. So a synergistic approach is called for. The conventional departmental structure of governments and government agencies, and the departmentalisation of faculties and disciplines in universities and research institutes, are obstacles to this. The creative changes, on which the shift to a people-centred, environmentally sustainable economy will depend, must continue to come largely from NGOs, citizens’ groups and other outsiders, and not from governmental, professional and academic establishments.

The need, then, is not just to tackle a multitude of separate economic problems, but to change the way the economic system works as a whole. The three following examples illustrate this.

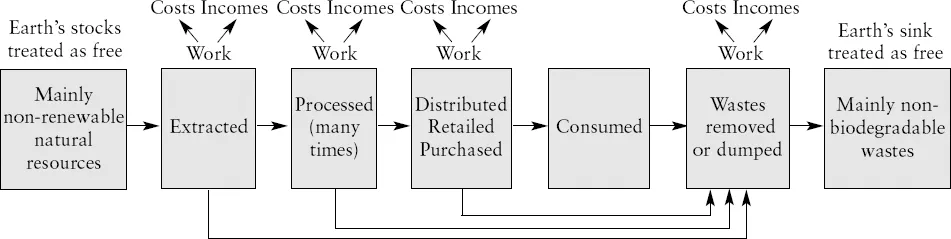

The Ecological Economy As A Circular System

Conventional economics has been based on a linear model of economic activities (as in Diagram 3 below). Material resources are extracted from Nature’s supposedly unlimited pool, outside the economic system; they are then processed stage by stage into the eventual manufacture of consumer goods; those are then distributed and consumed, and the final wastes are dumped in Nature’s unlimited sink, again outside the economic system. The capacity of Nature’s resource pool and the capacity of Nature’s waste sink have been treated as free goods, of no value. Values and costs, it has been assumed (the labour theory of value), arise only from the human work and enterprise involved in extracting the resources, processing them into goods, distributing them to consumers, and disposing of the wastes. Paradoxically, in the course of time it has been the fruits of human work and enterprise that have come to bear the main burden of taxation.

Diagram 3

THE ECONOMIC SYSTEM: LINEAR MODE

THE ECONOMIC SYSTEM: LINEAR MODE

Land is one of the most important natural resources. From time to time past thinkers like Thomas Paine at the end of the 18th century and Henry George at the end of the 19th have argued that land does have a value and that landowners should pay rent to the community for it. But this has so far been successfully resisted by the rich and powerful, whose wealth and power has been based on their having ‘enclosed’ the value of land and other natural resources in their own countries—and as colonial and post-colonial powers in the world economy. Their resistance has had the backing of political theorists like John Locke, and by most professional economists—the great majority of whom have been directly or indirectly in their employment. But now, as taxation of energy, resources and pollution climbs higher up the agenda of sustainable development, and as pressure grows for greater economic democracy and social inclusion alongside conventional political democracy, the case for taxing land along with other resources will become stronger.

The economic system will look very different when understood as a circular system, as Diagram 4 suggests. It will then be seen, no longer as a machine attached externally to the natural world, but as an integral part of it, consisting of countless interrelated circular subprocesses so designed that wastes provide resources for other subprocesses and are reduced to a minimum. Value will be attributed to natural resources, including the environment’s capacity to absorb waste and pollution. People and organisations using them or monopolising them will pay for the value they subtract by doing so, instead of being taxed on the values they add by their work and enterprise. The resulting higher costs of resource use and pollution (and lower costs of employing human effort and skills) will stimulate greater technical efficiency in the use of resources, and greater attention to reducing demand for them. Today’s levels of resource use, wastage and pollution need to be reduced b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword by Herbert Girardet

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction and Summary

- Chapter 1 Transforming The System

- Chapter 2 A Common Pattern

- Chapter 3 Sharing The Value of Common Resources

- Chapter 4 Money and Finance

- Chapter 5 The Global Economy

- Appendix I Some Organisations and Groups

- Appendix II References and Bibliography