eBook - ePub

Drugs without the hot air

Making sense of legal and illegal drugs

David Nutt

This is a test

Share book

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drugs without the hot air

Making sense of legal and illegal drugs

David Nutt

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The dangers of illegal drugs are well known and rarely disputed, but how harmful are alcohol and tobacco by comparison? What are we missing by banning medical research into magic mushrooms, LSD and cannabis? Can they be sources of valuable treatments? The second edition of Drugs without the hot air looks at the science to allow anyone to make rational decisions based on objective evidence, asking: *What is addiction? Is there an addictive personality? *What is the role of cannabis in treating epilepsy? *How harmful is vaping? *How can psychedelics treat depression? *Where is the opioid crisis taking us?

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Drugs without the hot air an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Drugs without the hot air by David Nutt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Neuroscience. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1. Why I had to write this book

†Tom Brake Member of UK Parliament: “Does the Prime Minister believe that once a healthier relationship is established between politicians and the media, it will be easier for Governments to adopt evidence-based policy in relation to, for instance, tackling drugs?”

David Cameron (the then prime minister): “That is a lovely idea”

I have included this political interchange at the start of this book to emphasize an issue that will come up in almost every chapter: the role of politicians and the media in overruling scientific evidence in the making of drugs policy. The above exchange occurred in 2011, and if anything, the situation in both the UK and US has deteriorated since then. The UK introduced the Psychoactive Substances Act in 2016, which makes all substances that affect the brain illegal – unless they are alcohol, tobacco or caffeine. In the US there were more than 60,000 deaths from opioids in 2017, a total greater than all the American deaths in the Vietnam war. Drugs are a perennial and growing problem in our societies.

However, challenging current policies is fraught with problems as my own case illustrates. Many British people who don’t recognize my name or know anything about my work will nonetheless remember me as “the government scientist who got sacked”. In many ways my departure from the UK government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) was my reason for writing this book, so it makes sense to start the story there. Fewer US citizens will have heard of me, though I did work in the US from 1986–1988, where I was head of the clinical research ward at the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism on the vast NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. It was my deep knowledge of the harms of alcohol that eventually got me sacked by the UK government.

In October 2009, †a lecture I’d given a few months before was released as a pamphlet on the internet. For some reason – perhaps it was a slow news day – this got picked up by the media and I was interviewed on BBC Radio 4. This generated more interest and several more interviews. A few days later I received an email from the then Home Secretary Alan Johnson asking me to resign from my position as chair of the ACMD. When I refused he released a statement saying that I had been sacked.

The lecture that sparked off this chain of events had covered a number of topics, but all the media wanted to talk about were my views on cannabis. The decision to downgrade cannabis to Class C was taken in 2004 and implemented in 2005, but in January 2009 it was re-upgraded to Class B, indicating increased harmfulness; the change was made against the recommendation of the ACMD. Jacqui Smith, who was Home Secretary at the time, justified ignoring the recommendations of our report because, she said, her †“decision takes into account issues such as public perception and the needs and consequences for policing priorities. … Where there is … doubt about the potential harm that will be caused, we must err on the side of caution and protect the public.” In the lecture, I discussed whether this was a rational approach, and particularly whether putting a drug in a higher legal Class in order to “err on the side of caution” would actually protect the public and reduce harm. And why did she not act on a drug where there was proof of harms – alcohol?

I’d entitled my lecture Estimating Drug Harms: A Risky Business? because I knew from experience that talking about the harm done by drugs in relative terms was considered politically sensitive. This had been made very clear to me when a scientific editorial I’d written the year before, comparing the harms of ecstasy with those of horse riding, provoked questions in Parliament and an unhappy personal call from Jacqui Smith. (You can read more about this episode on page 22.)

There had been a similar reaction to a †paper I co-wrote in 2007, which tried to rank 20 drugs in order of harmfulness, taking into account 9 different sorts of harm, including physical, psychological and social factors. What was remarkable about this paper was our finding that alcohol was the 4th most harmful drug in the UK – below heroin and crack cocaine but above tobacco, cannabis and psychedelics. Since alcohol was legal this challenged the logic underpinning the drug regulations which were supposed to be based on harms.

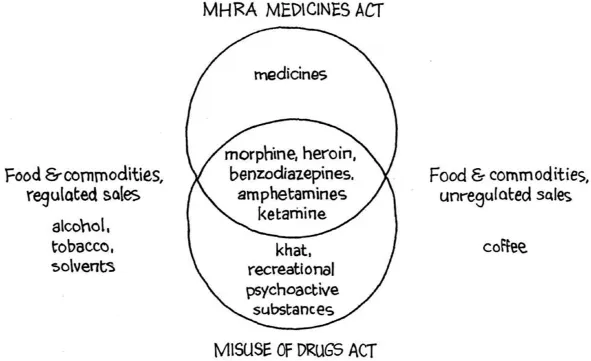

Politicians didn’t like the idea of some drugs being openly acknowledged as “less harmful” than others (or even worse, less harmful than legal drugs such as alcohol), because it might be seen as encouraging more people to use them, or make the politicians seem less “tough” in the eyes of the tabloid newspapers. This is despite the fact that the purpose of having different Classes of drugs built into the Misuse of Drugs Act – or the US controlled drug regulations – is to communicate to the public a degree of relative harm †(Table 1.1). Class B drugs should be less harmful than Class As, and Class C drugs less harmful than Class Bs. Incidentally, many drugs that have medical uses are both covered by the Misuse of Drugs Act, and regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the Medicines Act (Figure 1.1). In the US the situation is similar but the classification system uses Schedules rather than Classes and has more of them. Confusingly the US Schedules don’t always match with those in the UN Conventions, and in the US penalties are specific to each drug rather than determined by the drug’s Schedule.

Class | Includes | Possession | Dealing |

A | Ecstasy, LSD, heroin, cocaine, crack, magic mushrooms, amphetamines (injected) | 7 years | Life |

B | Amphetamines, cannabis, Ritalin, Ketamine | 5 years | 14 years |

C | Tranquillizers, some painkillers, GHB | 2 years | 14 years |

Table 1.1: The maximum prison sentences laid down by the UK Misuse of Drugs Act.

Figure 1.1: Many drugs are controlled as both medicines and as illegal drugs in the UK and US.

Which brings us back to cannabis – the only drug in the history of the UK Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 ever to be downgraded, following recommendations made by the †Runciman report in the year 2000. After the downgrading of cannabis, however, the media, along with some politicians and medical professionals, became concerned that stronger forms of the drug (known as “skunk”) were causing serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia.

There was certainly a legitimate question as to whether new breeds of cannabis were more harmful than the sort that had been considered by Runciman and the ACMD in the past. As the government’s advisory council, this is exactly the sort of issue that our research was supposed to address, and we undertook a very thorough study – one of the most comprehensive ever. Our conclusion was that, although there probably was a causal link between smoking cannabis and some cases of schizophrenia, this link was weak and didn’t justify moving the drug up to the next Class. Yes, there was a risk of developing a serious mental illness after using the drug, but it was smaller than the risks posed by other Class Bs such as amphetamines, which can also cause psychosis. This was the message that we wanted to send to the public by keeping cannabis in Class C.

Certainly, nobody was calling cannabis safe. However, as my 2007 Lancet report had shown (and as confirmed by our †2010 Lancet paper) across a range of different sorts of harm, cannabis was by no means as damaging as many other drugs, particularly alcohol. This was a point I made in my lecture, and which got picked up in the radio interview: “surely you can’t be saying alcohol is more harmful than cannabis?” I replied yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying, it’s there in my 2007 Lancet paper, which at the time was reported on the front page of two of the leading UK newspapers – the Independent and the Guardian – so it was hardly a secret. But this question was repeated in the other interviews that week – everybody wanted the quote that alcohol was more harmful than cannabis. It was an entirely defensible thing to say, as it was based on my own scientific work, and backed up by a similar study from Holland which had agreed that alcohol deserved to be ranked among the most harmful of drugs. In these interviews I also observed that the government had asked the ACMD to determine which Class cannabis belonged in, but then hadn’t followed our advice.

†In a letter to the Guardian a few days after he sacked me, the UK government’s Home Secretary Alan Johnson explained that I “was asked to go because he cannot be both a government adviser and a campaigner against government policy.” †I responded in The Times that I didn’t understand what he meant when he said I had crossed the line from scie...